In the Museum of London’s collection there are over 800 Christmas cards, many of which date back to the Victorian era. While themes of birds, flowers and Nativity scenes were common, competition and a desire for originality gave rise to a highly successful genre of novelty cards. We trace the origins of why — on some cards — policemen got whacked by clowns, hares rode Penny Farthing bikes and insects wished you a Merry Christmas!

While most of the £162 million (2020) UK Christmas card sector showcases beautiful floral designs, birds and Christmas symbolism, there is a significant genre of cards that are outright funny, satirical, political, and even include pranks! Such novelty cards can be traced back to the Victorians, who “had a delightful childlike taste in what they considered artistic pleasures and enjoyments beneath the discipline in their daily lives”. Over the years, these designs ranged from humanised animals and birds, to scary, and even occasionally violent clowns. The appearance of a dead birds (often robins with messages of “calm decay and Peace Divine”) and creepy insects in the late 19th century have baffled many card collectors in the past, and continue to do so today.

In the Museum of London’s collection there are over 800 Christmas cards, many of which date back to the Victorian era. Here we train the spotlight on some of the more unusual or non-traditional Christmas cards in our collection. But first, a brief history of Christmas greeting cards.

The first among equals

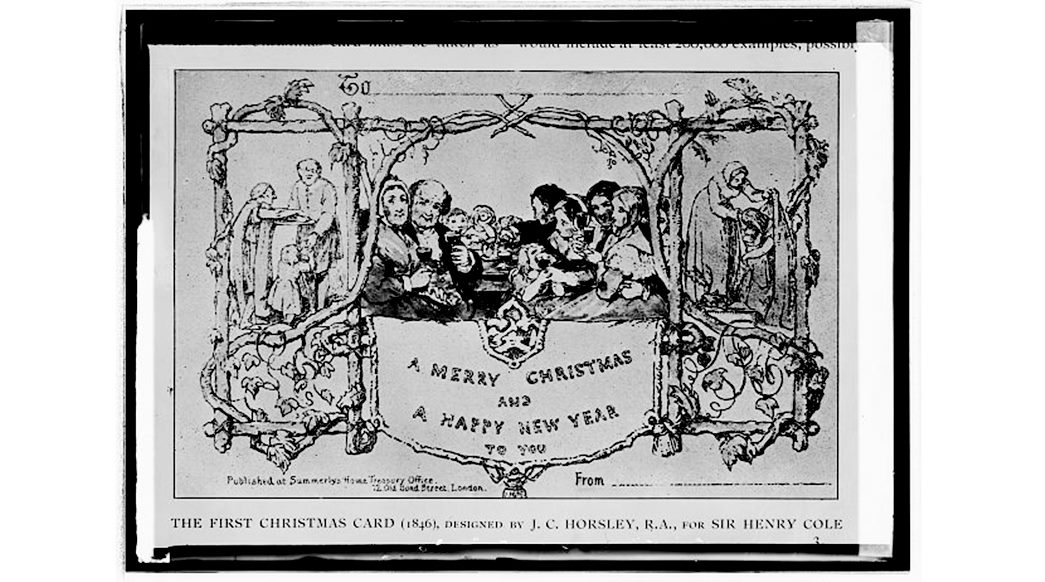

A glass negative of the first commercially produced Christmas card from 1843. (Courtesy: Library of Congress, Prints & Photographs Division, LC-DIG-npcc-27613)

The first card

The first commercially produced Christmas card is said to have been designed in 1843 by artist John Callcott Horsley for British civil servant and inventor Sir Henry Cole, to send to his friends. It was produced three years after the introduction of the Uniform Penny Post, which allowed people to send cards at a standard cost. Initially, though, Christmas cards were expensive to produce, with Sir Henry Cole’s cards selling for 1 shilling each. Production was made cheaper by developments in new printing processes and led to more variety in design.

They were initially produced by Valentine’s card printers, who were looking to expand. This is reflected in how early Christmas cards often contained romantic imagery, and the types of spring flowers on the cards could be used to send a variety of messages. The language of flowers may not be as familiar to us now, but the Victorians made an art of it, allowing the sender to convey their feelings without committing them to writing. Roses for love, we know, but would we send a foxglove for insincerity or a yellow carnation for rejection?

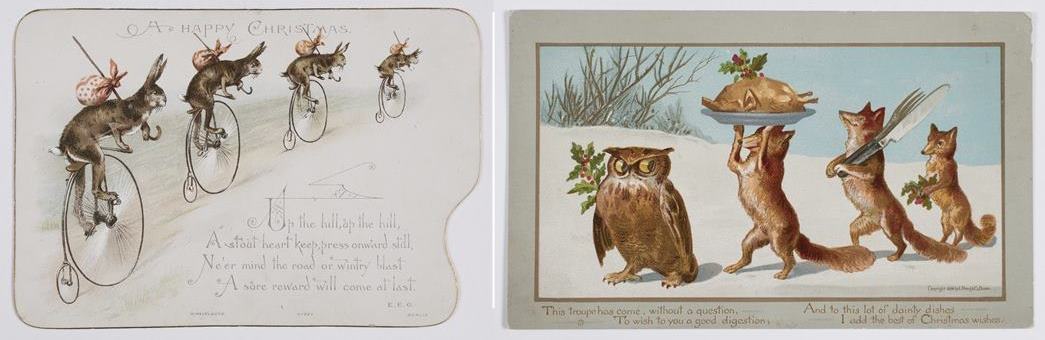

Christmas trees, robins and Father Christmas were still popular themes during the 19th century, but designing cards was serious business. They were regarded as art, with card companies commissioning prominent artists to produce new designs. Competitions were held, and Christmas cards were extensively reviewed in national press, much like books and movies today. It was around this time that joke cards featuring animals in human poses became popular. These included “comic animals and cards poking fun at the Aesthetic Movement [1]. Towards the end of the century, designs reflected the influences of Art Nouveau [2] and the decadence of fin de siècle [3],” writes George Buday in The History of the Christmas Card.

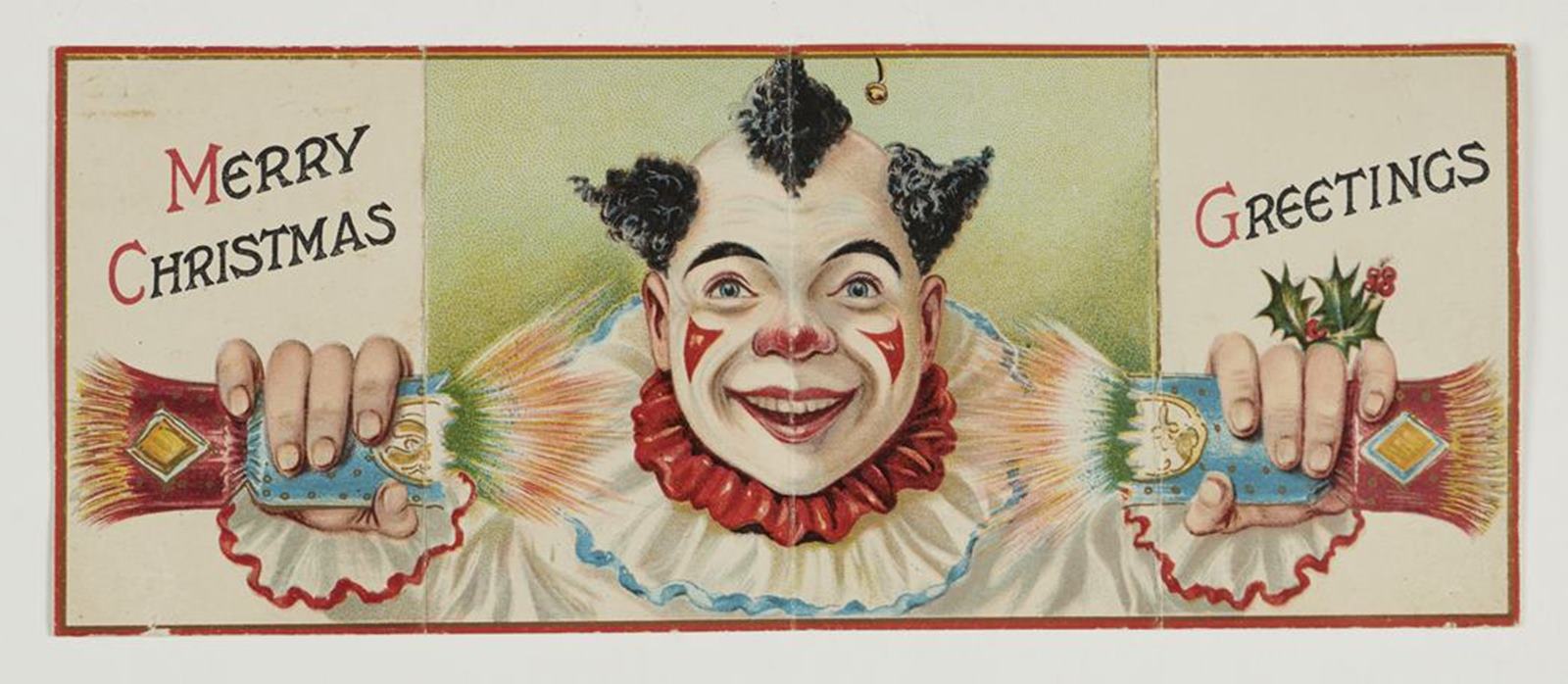

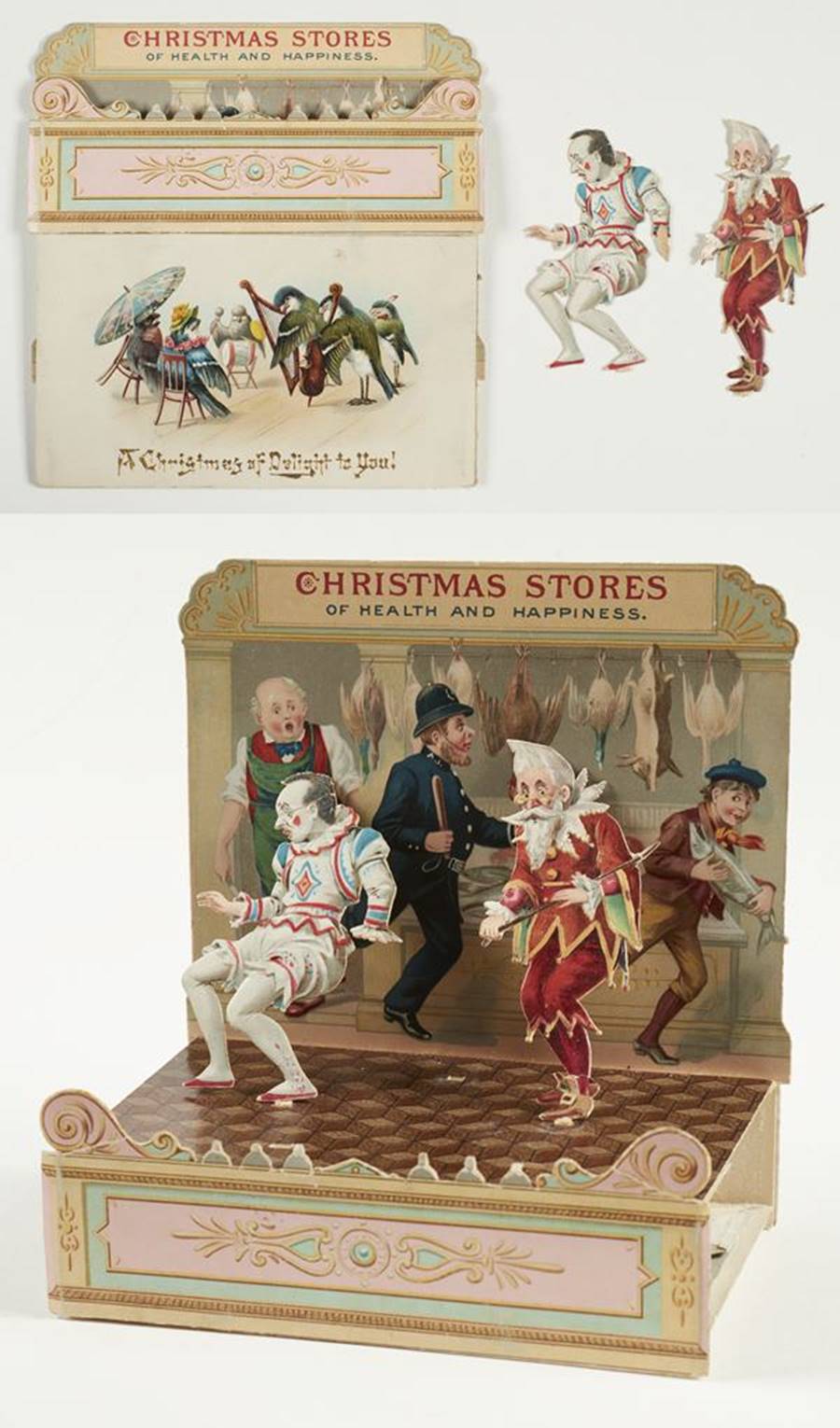

Increased competition encouraged artists to be more original to keep up the interest of customers of a rapidly growing seasonal market. Alongside novelty cards, mechanical fold-out or pop-up cards gained popularity and were often paired with pranks and hidden messages. Like the ones produced by the early card manufacture Jonathan King, many examples of whose Valentine’s cards can be found in the museum’s collection.

No One-Trick Pony

Going back to novelty cards, among animals, dogs, cats and rabbits were quite popular as can be seen in the collection — often wearing oversized bows and in festive settings. This theme could be reflective of the everlasting British fondness for pets. It’s also said that cards with humanised animals in everyday scenarios were primarily meant for children, but they enchanted adults too. In 1859, Charles Darwin published On the Origin of Species and this could have influenced some of the designs for such cards as well. “Grotesque parallels and an emphasis on the similarity between animals and certain human characters and features were natural subjects to delight almost everyone,” writes Buday. Humorous verses also accompanied the imagery sometimes, indicating that the subject is not meant to be taken too seriously.

'Tis a season to be jolly

(left) ‘Up the hill, up the hill, A stout heart keep, press onward still. Ne’er mind the road or wintery blast. A sure reward will come at last’ (ID no.: 38.254/221). (right) ‘This troupe has come, without a question, to wish to you a good digestion, and to this lot of dainty dishes I add the best of Christmas wishes.’ (ID no.: 74.370/1xxxviii)

The tale of fly (or three)

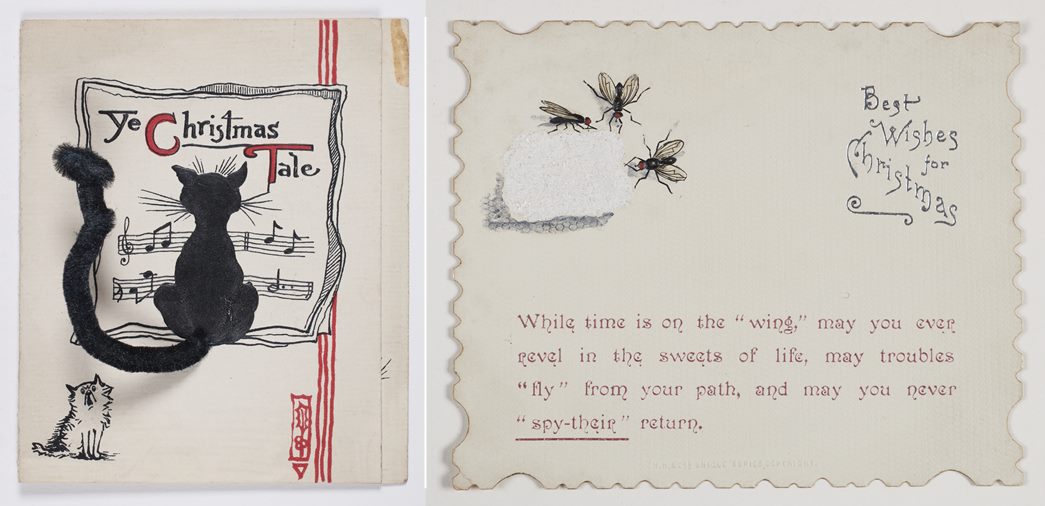

(left) A black cat with a pipe cleaner for a tail that quivers when the card is moved (ID no.: 74.370/1vi). (right) ‘While time is on the “wing”, may you ever revel in the sweets of life, may troubles “fly” from your path, and may you never “spy-their” return.’ (ID no.: 74.370/1xlvii)

![The reverse of this card reads: ‘This Christmas let’s annihilate Drink and it’s [sic] hollow joys; Use drinks that ne’er inebriate, and shun that which destroys. So hey! For tea and harmless drink, pure water with good health, light rising, and brain clear, to think, With peace, and work, and wealth!’ (ID no.: 38.254/136)](/application/files/6916/3823/0983/5_Christmas_cards_novelty_450_tea_leaves_humour_cards_MoL.jpg)

The reverse of this card reads: ‘This Christmas let’s annihilate Drink and it’s [sic] hollow joys; Use drinks that ne’er inebriate, and shun that which destroys. So hey! For tea and harmless drink, pure water with good health, light rising, and brain clear, to think, With peace, and work, and wealth!’ (ID no.: 38.254/136)

Puns, riddles and satire

Christmas has always been a time for fun and games, and many of the cards in the collection feature puns, riddles and satire. Some of the word play is relatively simple, like the card captioned ‘Ye Christmas Tale’, with a pipe cleaner for the cat’s tail! This was possibly aimed at children, but cards with more complex verses and riddles are likely to have been aimed at an older audience. However, such ‘unlovely cards’ were disapproved by card critics of the time, and many considered them beneath their notice, in contrast to their popularity. Yet curiously there are a number of examples of creepy-crawly insects appearing on early Christmas cards. One rather grotesque card encouraging troubles to ‘fly’ depicts three flies on a sugar cube! Rats and mice often decorated Victorian Christmas cards, which was a curious choice given the perpetual war waged against them by homemakers.

Another genre was of those cards sporting puns, riddles and hidden messages, like one of a teacup with the message ‘with best wishes’ hidden in the tea leaves. From this card we not only learn about the popularity of tea drinking, but the practice of reading tea leaves as well. Interestingly, the verse on the back gives a warning against drinking alcohol. Additionally, many cards in the museum’s collection feature porcelain, highlighting that this was something else that wealthy Victorians liked to collect. Sets and series of Christmas cards were also collected and a number of examples appear in the collection, like the set of four cards of theatre attendees, which makes a satirical comment about the different social classes.

Clowning around

According to Arthur Blair (author, Christmas Cards for the Collector), “as the novelty of snow scenes, holly and robins became commonplace…more designs of a humorous nature began to appear…and the pranks of children…joined the contrived ‘humour’ of unfortunate men falling through the ice, clowns knocking down policemen and other such happenings that often raise unsympathetic laughter from the onlooker but never the victim.” Of these, clowns were an especially popular character on Christmas cards. The association could be theatrical, as clowns (often appearing creepy or sinister) were common in Christmas pantomimes, and would have been hired as children’s entertainers at parties. Similar to the Shakespearean ‘fool’ or the medieval ‘court jester’, the clowns on these cards were shown poking fun at anyone and everyone! Some cards show them instigating practical jokes or just a cheeky socio-political comment, such as one with a clown hitting a policeman with a dead goose, captioned “a little sauce with his goose”.

It is currently estimated that around a billion Christmas cards are sent every year in the United Kingdom alone. However, it’s interesting to see that while on the one hand some design themes — such as spring flowers, birds, quote cards, humorous animals and nativity scenes — have not significantly changed, on the other, there are distinct changes in style, subject matter and innovation across time. In fact, in some cases, there are some old cards — related to nudity, racism and class distinction — which would be considered absolutely unacceptable today.

While we may not see Christmas card reviews in national press any longer, it cannot be denied that they are art works in their own right, and occasionally a quirky commentary on everyday life. What this foray into novelty cards shows is that this is an ever-evolving industry, with a vibrant and often inexplicable history. So the next time you see a card with a violin-playing cat or mischievous clown, give a nod to this Victorian tradition that continues to capture our interest.

[1] A late 19th-century movement that championed pure beauty and 'art for art's sake' emphasising the visual and sensual qualities of art and design over practical, moral or narrative considerations.

[2] An ornamental style of art that flourished between about 1890 and 1910 throughout Europe and the United States. Art Nouveau is characterised by its use of a long, sinuous, organic line and was employed most often in architecture, interior design, jewellery and glass design, posters and illustration.

[3] Relating to or characteristic of the end of a century, especially the 19th century.