A pencil and watercolour drawing on four sheets of paper, the Rhinebeck Panorama provides an extraordinary bird's-eye view of London — it’s like imagining yourself floating across the city in a hot air balloon — all the way to Windsor Castle!

A bird’s-eye view?

In an age of planes, drones and skyscrapers, it’s easy to make expansive aerial views of London. It was not always so, of course. Yet, the desire to capture the whole city in one all-encompassing image has a long history, dating back at least to the 17th century.

London from Southwark, made around 1630, is one of just three surviving paintings of London before the Great Fire of 1666. Like many early views, it shows the city from the south, looking north. In the foreground, we can see Southwark, with the theatres on the left and Southwark Cathedral to the right. Spanning the Thames is the old London Bridge, bearing the decapitated heads of criminals. The bridge leads the eye up to the City of London itself, bristling with close packed houses, church towers, and dominated by old St Paul’s Cathedral. The image is not quite accurate, though. The vista has been squashed to include the river’s curve on the right.

Most subsequent comprehensive views also show London as if looking north from Southwark. A General View of London and Westminster, a series of five mid-18th century engravings by the Buck Brothers, is a case in point. In order to include Westminster, the brothers have flattened the perspective by straightening the meandering Thames. This allows them to balance London’s two main centres of influence: politics at Westminster, on the left; money in the City, on the right. Nevertheless, the print is remarkable for its accuracy. Comparison shows the image fits consistently with mid-18th century maps. But, to achieve such breadth meant the image had to be spread across five sheets of paper.

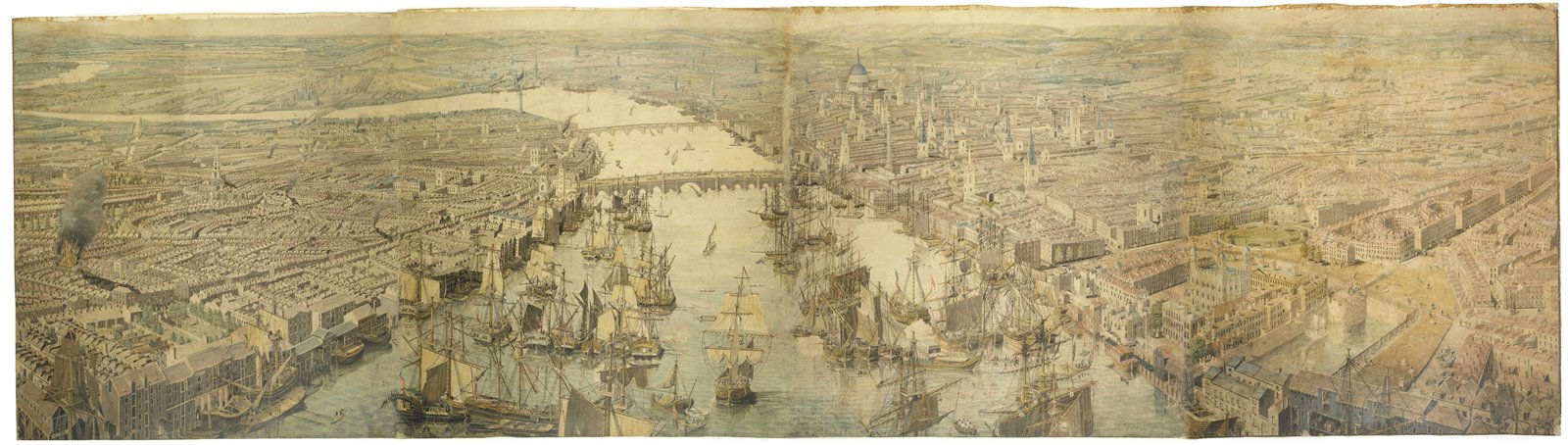

The 'Rhinebeck' Panorama changes all of this. A pencil and watercolour drawing on four sheets of paper, it provides an extraordinary bird's-eye view of London around 1806, from a point roughly where Tower Bridge now stands. In one 180° sweep, the Rhinebeck Panorama completely alters how we see London. We no longer look north but west. And we see London in its entirety, rather than as a flattened riverbank with two centres of power at either end.

Towards the end of the 18th century, a fascination for all-encompassing views became fashionable, when huge 360° paintings began to be exhibited in purpose built rotundas. In fact, the word ‘panorama’ (Greek for ‘all-embracing view’) was coined in 1791 to describe these paintings. A precursor to cinema and virtual reality, they became a massive hit with the public. As one 19th-century visitor put it:

The effect is very astonishing. I actually put on my hat imagining myself to be in the open air.

Because they were too big to preserve, few of these canvases survive. What remain are the preparatory drawings and paintings. It may be that the Rhinebeck Panorama is one of these, a study for a much larger panoramic canvas, meant to give the illusion that the viewer really was hovering over the city. However, most publicly displayed panoramas were fully circular, whereas Rhinebeck is a semi-circular view. It might, on the other hand, have been one of the watercolour views of the principal cities of Europe shown in a London in 1809. These were displayed ‘upon the principle of Panoramas by mechanical and optical aid, illuminated by gas lights’. Whatever its purpose, the Rhinebeck clearly shows the influence of the panorama craze.

The drawing focuses on the Pool of London and the shipping loading and unloading goods on the wharves of Bermondsey.

Despite the sense of peace and prosperity, England was still deeply embroiled in the Napoleonic Wars at this time. The decisive naval battle of Trafalgar, for instance, had taken place shortly before the drawing was made. Britain (and, of course, London) was growing in economic power largely due to the Royal Navy's command of the seas. The drawing reminds us of this. Amidst the shipping clogging the foreground is a warship with two masts removed. It was onto such receiving ships that men unfortunate enough to be press-ganged were brought after being “recruited” into the Royal Navy.

The streets of Southwark and Lambeth spread out to the left, and somewhere in their midst, the fire brigade battles a huge blaze.

Over to the right, on the City side, a man flies a kite as fashionable women stroll in the shadow of the Tower of London.

Connecting the north and south banks is the old London Bridge — though, by this time, heavily remodelled — with carts and carriages rattling across it. In the middle-distance lies Westminster, but to the left, due to the snaking course of the Thames. Beyond are the suburbs of Battersea and Chelsea, and the villages of Fulham, Hammersmith and Kew. Farther off, the panorama embraces the hills of Highgate and Hampstead, and the surrounding countryside. On the horizon, over 20 miles distant, we can just see Windsor Castle, a subtle reminder that London is the capital city of the wider nation.

Aside from the topography, what the Rhinebeck Panorama shows is, essentially, the London conjured a few years earlier by William Wordsworth. In his poem Lines Composed upon Westminster Bridge, 3 September 1802, he wrote:

Earth has nothing to shew more fair […]

Ships, towers, domes, theatres, and temples lie

Open unto the fields, and to the sky;

All bright and glittering in the smokeless air.

Would the air have been smokeless? In her journal, Dorothy Wordsworth, the poet’s sister, remarked on crossing Westminster Bridge that “the houses were not overhung by their cloud of smoke”. This suggests how, even in the early 19th century, the sheer number of coal-burning fires for heating and for driving industry created a distinct pall over the city — one all the more notable when absent. By 1819, London “particulars”, especially dense, lingering fogs, were already becoming a sufficient issue for Parliament to establish a select committee to consider the “problem of smoke from steam engines and furnaces”. In 1810, then, it is likely that London would have basked only rarely under such luminous skies as the Rhinebeck Panorama presents us with.

The drawing is the work of three artists. One painted the shipping, though the vessels do not always tally with the historical record. A second painted the cityscape itself, which though generally correct shows some inconsistencies. And yet a third painted the distant church spires, but did so out of proportion with the surrounding buildings. So, although the overall impression is convincing, the scene is not entirely accurate.

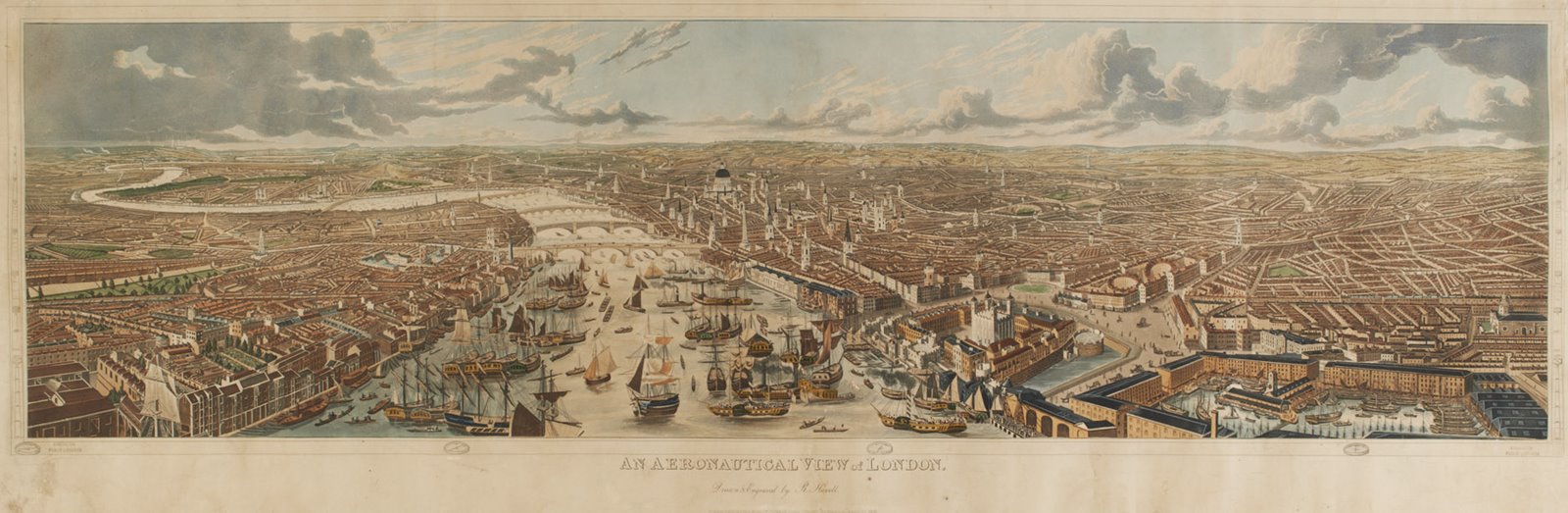

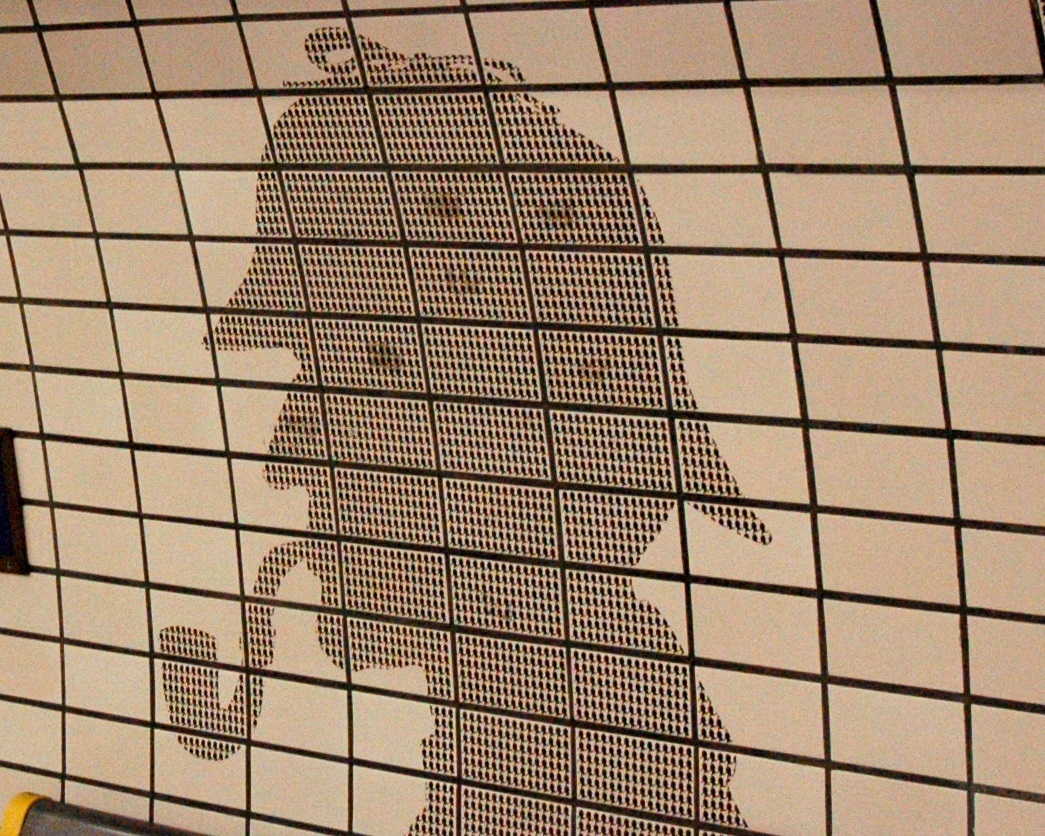

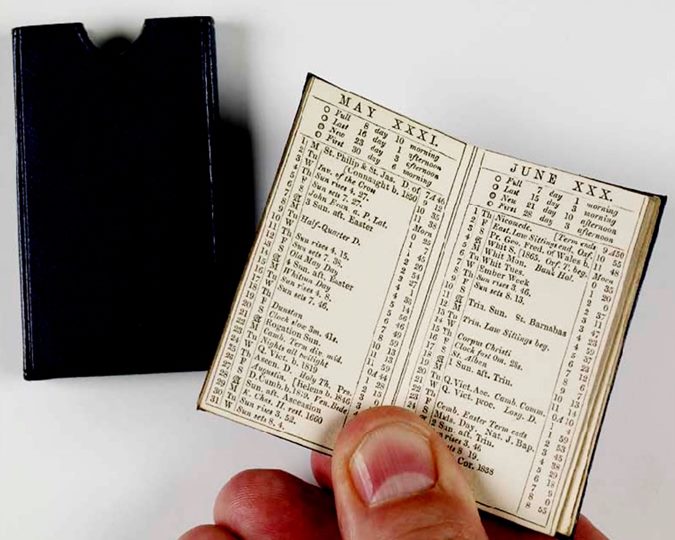

Who these artists were we do not know. However, by the 1830s, the artist-engraver, Robert Havell, Jr (1793-1878) must have had the drawings. In 1832, he produced an engraving entitled An Aeronautical View of London, which is closely modelled on the Rhinebeck Panorama, though on a smaller scale, and brought up to date. It includes, most obviously, John Rennie’s “new” London Bridge, which opened in 1831.Havell later emigrated to the USA, settling at Tarrytown on the Hudson River, in New York state. Which brings us to perhaps the most bizarre part of the panorama’s story. Apparently, Havell took the panorama with him to America, for this remarkable drawing was discovered lining a barrel of pistols in Rhinebeck, some miles north of Tarrytown, in 1941. Fortunately, its significance was recognised. In 1998, the museum acquired it and the panorama returned to London after almost 200 years.