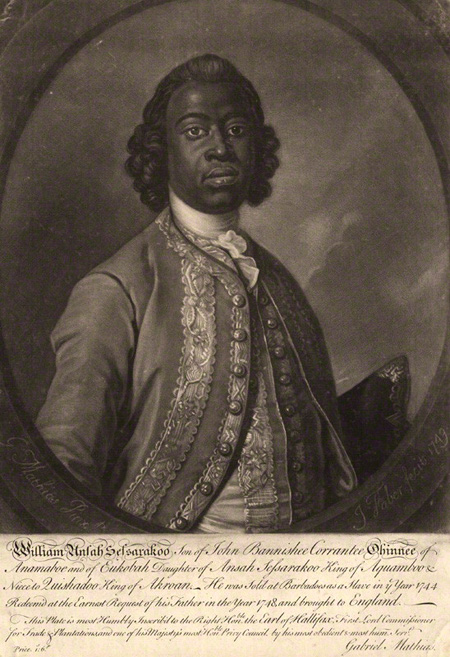

Explore an extraordinary story about the first days of the slave trade, and one man’s journey from African prince through slavery into London high society.

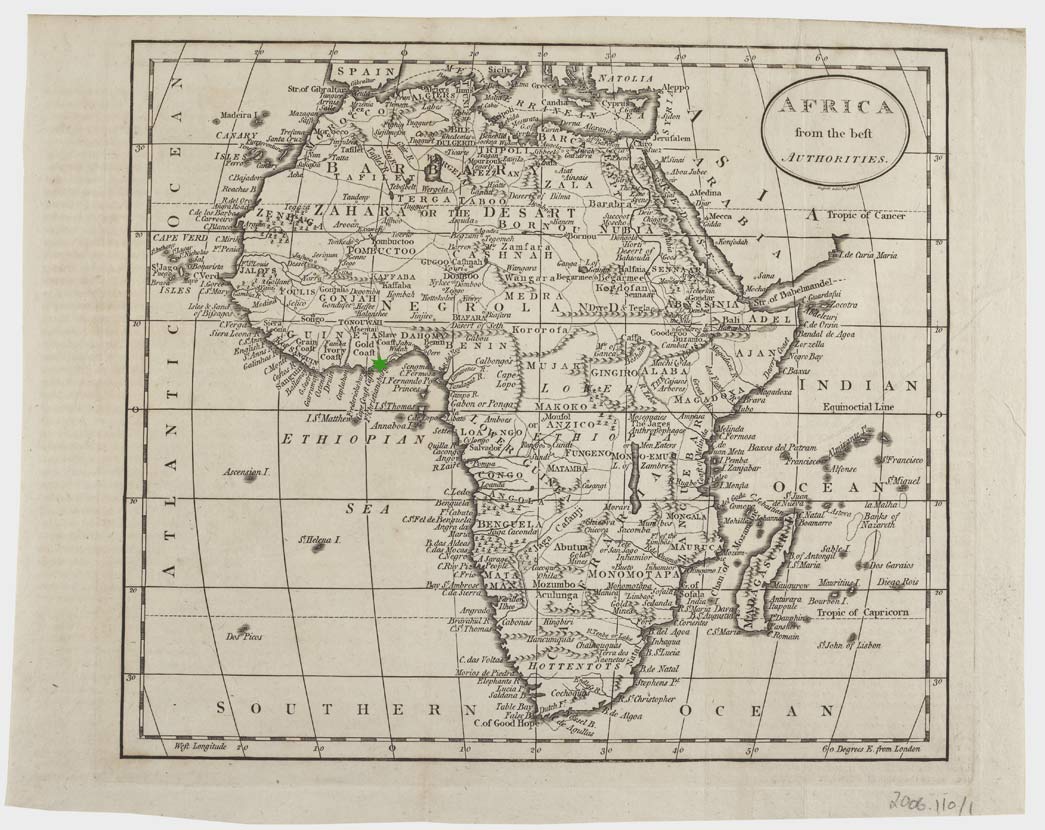

William Ansah Sessarakoo by John Faber Jr

Mid 18th century. © National Portrait Gallery, London. NPG D9199

A 2016 display at the Museum of London Docklands, The Royal African, featured the life of William Ansah Sessarakoo, a man from west Africa who arrived in London society in 1749. Sessarakoo was a member of the most important ‘ruling’ family living on the coast at Anomabu, in what is now Ghana. He was sent to England to be educated, but an English slave trader duped him and sold him into slavery in Barbados.

The Royal African Company, which ran England’s network of forts on the west African coast, freed Sessarakoo. They organised for the young royal to witness the opulence of London society. We spoke to the museum’s Head of History Alex Werner & historian Dr. William Pettigrew, author of Freedom's Debt, about the unscrupulous motives behind the Royal African Company’s generosity.

Alex Werner: I met the historian Dr William Pettigrew in February and he talked about his research into the Royal African Company. The story of the company was really intriguing, and I felt that it would make an excellent exhibition at the Museum of London Docklands. The London Sugar and Slavery gallery, which begins by explaining the rich culture of Africa before Europeans arrived, does not really examine in depth the history of slave trade in the 17th century. In the exhibition we look at the time when the Royal African Company was first being established under the patronage of King Charles II in the 1670s.

Dr. William Pettigrew: Charles gave the Company a monopoly over all English trade on the west coast of Africa for 1000 years. So they had the exclusive right to trade English woollen cloth, alcohol, and firearms for African gold, redwood dyes, ivory, and enslaved people. There was a lot of money to be made, big profits for the City of London merchants and royal courtiers who invested in the Company. And the most prominent of those men were King Charles and his brother the Duke of York, later King James II.

Alex: Those connections made the Royal African Company extremely powerful- for example, when independent English slave traders tried to operate in west Africa, the Royal Navy would sometimes seize their ships and goods. The Royal African Company built a series of forts along the west African coast to promote and protect their trade. The Royal African Company shipped about 150,000 people across the Atlantic from the late 1600s to the early 1700s. Clearly, this is a story worth telling.

This side of the story of London’s involvement with Africa is much less well known- most people, I think, associate the slave trade with the 18th century or later, with William Wilberforce and the infamous diagrams of slave ships. Why do you think that is?

Alex: I think that in 2007, the bicentenary of the abolition of the slave trade focused people’s minds on the early 19th century, and the struggle to abolish the trade in enslaved Africans and slavery itself. It’s interesting to consider the pivotal role that British people played in setting it up the slave trade. The forts built by the Royal African Company provided vital infrastructure for the trade in enslaved Africans.

Dr. Pettigrew: London's involvement in the trans-Atlantic trade in enslaved Africans is often understated. It's contribution amongst British cities was second only to Liverpool and its involvement was far longer - lasting throughout the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries and into the early nineteenth.

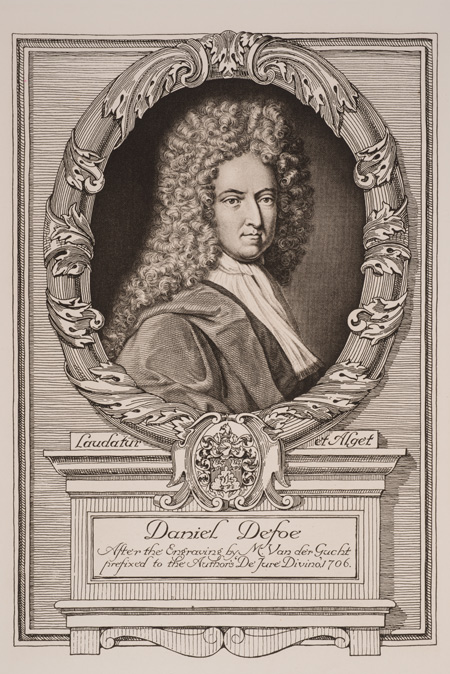

“Our Collonies in America, … could no more be maintain’d… without the supply of Negro Slaves… from Africa, Than London could subsist without the River of Thames.” – Daniel Defoe, The Review, 1709

Portrait of Daniel Defoe, 1706; ID no. 82.209/2

So why, if the Royal

African Company were so deeply involved with the slave trade, would they bring

William Sessarakoo to London?

Alex Werner: It’s all part of a fascinating conflict between the Royal African Company and independent London slave traders, known as 'separate traders', who resented the monopoly granted by the Company’s royal charter. The Company argued that if they were the only ones in charge, they would manage and control the trade in enslaved Africans & make it a less brutal process. So really, it turns into a propaganda war between the Royal African Company and the independent traders. In 1709, the African Company employed Daniel Defoe, author of Robinson Crusoe, to promote the company in pamphlets and a newspaper he edited- he was their spin doctor.

In 1688, the company’s governor and patron King James II abandons the English throne. That leads to a new relationship between the monarch and parliament, giving parliament more power. The slave traders focus on parliament to undermine the Royal African Company’s monopoly which diminishes by 1712. So when an independent slave trader sells William Sessarakoo, a member of west African royalty, into slavery in Barbados, the Company sees a public relations opportunity. They brought him to London in February of 1749. He impressed Georgian high society with his gentility and intelligence, and was the guest of the Earl of Halifax in Grosvenor Square.

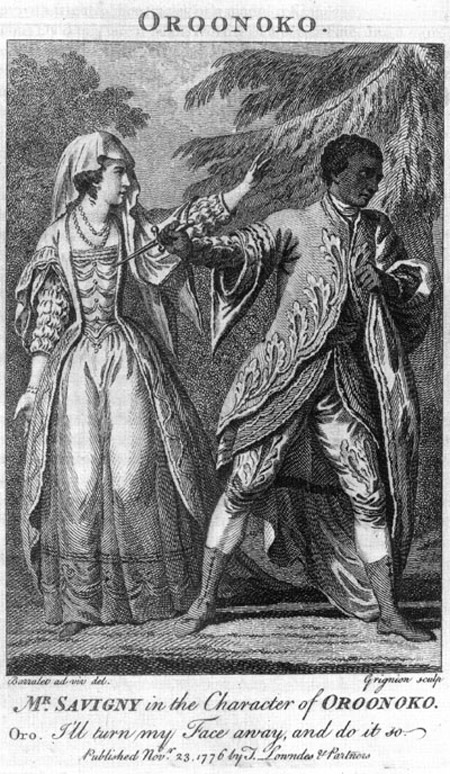

Illustration of a 1776 performance of Oroonoko

From the playbill, 23 November 1776. Public domain.

So their argument was actually that the slave trade was horrific and brutal - but only when it was done by people other than the Royal African Company?

Dr. Pettigrew: It is a sort of perverted logic- they claim that they would make the process less brutal, more organised. And the independent traders have their own arguments- they claim that free trade is a cherished English liberty. It’s a divine right of free born Englishmen to be able to enslave and sell Africans.

Weren’t both sides worried about horrifying the British public?

Alex: Most Londoners knew very little about the slave trade- there was limited abolitionist sentiment at this period. African public figures like Sessarakoo put a human face on the many thousands of people being enslaved.

On the evening of 1 February 1749, Sessarakoo attended a performance of Thomas Southerne’s Oroonoko at the Theatre Royal, Covent Garden. It was a play about an African prince tricked into slavery. The plot was so close to Sessarakoo’s own experience that he felt unable to watch and left the performance- newspapers reported on his discomfort. The audience was very moved by his departure.

That’s also one of the reasons why we’ve featured Sessarakoo so prominently in the exhibition. There’s this complex and rather impersonal conflict between the Royal African company and the free traders, about legality and trade and arguments in the corridors of Parliament. William Seassarakoo reminds us of the enslaved Africans whose fates were being debated in London. It’s especially appropriate to have this display in the Museum of London Docklands, which was originally a warehouse built to store plantation produce such as sugar and coffee produced and harvested by enslaved Africans in the Caribbean.

Dr. Pettigrew: This exhibition will help visitors understand a crucial chapter in that longer history of London-based slave traders. It will also challenge visitors to consider the perverse ways in which Britons have used their freedoms to justify an enlarged slave trade.

You can find out more about the research behind the display in Dr. Pettigrew's book Freedom's Debt: the Royal African Company and the Politics of the Atlantic Slave Trade, 1672-1752.