Disease and death have always terrified Londoners – and rightly so. While modern medical science and public health systems have enabled us to defend against plagues and pandemics, the people who walked London’s streets before us had to rely on other resources. Trying to understand the overwhelming and awful nature of disease, early Londoners turned to various forms of magic for personal protection.

Roman plague amulet, c.200-400 AD

Some of the earliest examples of this come in the form of magical amulets, which were prepared by the inhabitants of Roman London against plagues and infectious maladies. This amulet is inscribed with a protective spell or prayer to the gods; invoking their protection for the amulet’s owner, a man named Demetrios. Found in the Thames, it may have been thrown there deliberately, as a ritual offering. Other Roman amulets of this sort survive, including personal curses against specific individuals, presumably wishing some kind of personal or physical harm against them.

Of course, the line between magic and religion has always been a blurry one. Many of the ‘magical’ practices of the past would have been understood as matters of religious faith by their adherents. In medieval London, cheap lead badges purchased as souvenirs of holy pilgrimages were believed to hold magical protection against sickness. Many Londoners undertook pilgrimages to Canterbury, to the shrine of the London-born martyr Thomas Becket.

Pilgrim badge from the shrine of Thomas Becket, 14th century

The inexpensive, mass-produced pilgrim badges were touched against the shrine (which housed the physical relics of the martyr) in order to absorb some of its holy power. After this, they were thought to hold healing and protective properties in times of illness. In everyday sickness, the badges must have been a comfort – and during the horror of widespread plagues, such as the Black Death of 1349, perhaps the only hope of beleaguered Londoners as they watched their fellow citizens die in their thousands.

Pilgrim badges relied on the principle of ‘sympathetic magic’, whereby physical objects could represent individuals with magical powers. In the case of saints and martyrs, their magic was a welcome aid in times of sickness; but the principle also applied when trying to protect against witches and other agents of harmful magic.

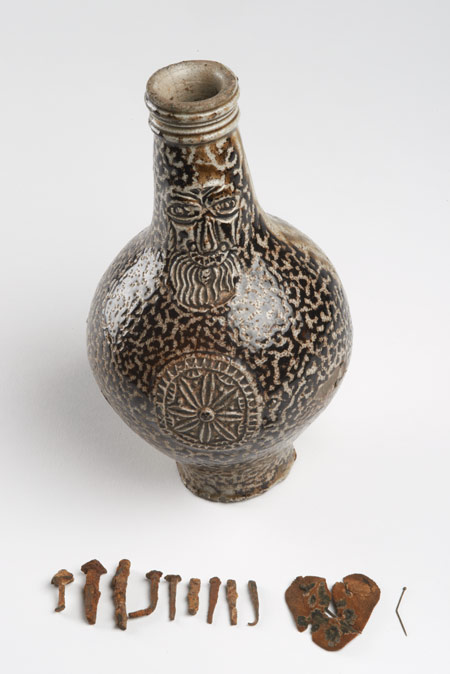

17th century stoneware Bartmann jug used as a witch bottle

Witch bottles, found in London buildings from the medieval period right through to the 19th century, were everyday bottles or jugs which had been filled with items believed to discourage witches. The combination of human urine and iron nails was a popular one, based on the belief that the bottle would transfer its power to the witch, and cause them to have painful urination.

Shoes were also invoked for their protective qualities, because they would suggest to the witch that a living human patrolled the area – these boots were deliberately placed within the roof of the Savoy Chapel on the Strand, as late as 1876.

Although many Londoners were increasingly sceptical of witchcraft by the 17th century, and the laws against witchcraft were struck down in 1735, the belief never entirely disappeared. Nor was the suspicion of witchcraft confined to impoverished or poorly educated people. The London diarist Samuel Pepys, who was a highly educated and influential figure, recorded conversations in which he and his friends shared their knowledge of protective charms and discussed other ‘enchantments and spells’.

As late as the 1680s, prosecutions for witchcraft were still taking place in London, with the accused generally on trial for causing the illness or death of an individual. In 1682, the Old Bailey heard the case of Jane Kent, indicted for witchcraft after supposedly bewitching a young girl named Elizabeth Chamblet. It was reported that Elizabeth ‘fell into a piteous condition, swelling all over her body, which was discoloured after a strange rate’, and subsequently died. The distraught father, who had previously argued with Jane Kent over the unsuccessful sale of some pigs, blamed witchcraft for the inexplicable death of his daughter. Kent was eventually acquitted, after numerous people testified to her good character and her regular attendance at church – but Elizabeth Chamblet’s mysterious ailment was never deduced.

Just as the distinction between magic and religion was a vague one, with holy powers in perpetual battle against witches and the devil, so too was the distinction between magic and science in early modern London. ‘Natural philosophers’ such as Sir Francis Bacon and Nicholas Culpeper combined their studies of logic, medicine and botany with experiments in alchemy, astrology and fortune-telling. These were not regarded as incompatible practices, but as complementary efforts towards understanding the natural universe, with the human body at its centre.

Culpeper, in particular, played a key role in bringing medical knowledge to a wider audience. A political radical, he believed in making medical knowledge available to public. He ran an apothecary (or pharmacy) from his home in Spitalfields – crucially, outside the authority of the City of London – and translated the Latin medical texts used by the Royal College of Physicians into English. Culpeper relied upon astrological observations in his research into herbal medicine. His 1652 publication, The English Physitian And Compleat Herbal, goes into considerable detail regarding the cosmic properties of plants as well as their medicinal benefits, recommending that plants be collected, prepared and administered under specific astrological conditions, to ensure their effectiveness for the patient.

While such beliefs may seem nonsensical to us today, modern Londoners have not completely abandoned their belief in magic as a precaution against disease. While our understanding of epidemiology, internal medicine and the immune system is a far cry from that of our Roman, medieval or early modern forebears, we still look to magic to comfort us and give us the illusion of control, when disease progresses beyond the limits of medical science. The modern ‘wellness’ industry, with its reliance upon detox supplements and crystals imbued with positive energy, is a new manifestation of our need to feel like we are doing something – anything – in the face of our own physical fragility.