In the first instalment of a series on London style, we delve into the wardrobes of the fashionable woman of the 1920s, and explore the clothes and accessories a well-to-do female Londoner would have slipped into for a night out in the capital.

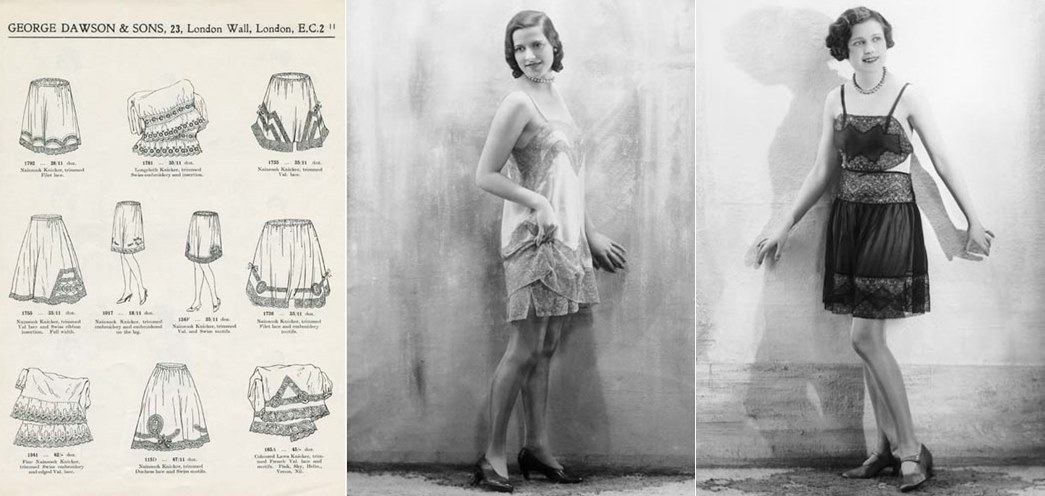

Snapshots from The Gold-Diggers (1927) featuring Tallulah Bankhead. (Courtesy: The Regents of the University of Michigan brochure)

What would a fashionable Londoner wear as she went out for a night of sophisticated revelry? To ogle the Prince of Wales at the Café de Paris, dance at the Criterion Ballroom, attend a tango tea at Chez Henri or let herself be seen in the beautiful dining room of the Café Royal. For inspiration, think American-born actress and fashion icon Tallulah Bankhead on the London stage in the 1920s, particularly in her role as Jerry Lamar in The Gold-Diggers at the Lyric Theatre in 1927. Watch a flash from the play here (courtesy British Pathé).

Some representations of the 1920s suggest that women spent all their time dancing in so-called ‘flapper dresses’, a tiara on their bobbed hair and a long string of pearls dangling from their neck, gracefully manipulating a cigarette inserted into a long holder.

While some women did and looked like this some of the time, there are other aspects to 1920s female fashion.

But first, what is a ‘flapper’ anyway?

The term first became associated with girls and young women towards the end of the 19th century and seems to have been adopted into common usage during World War I. The life of many women changed during the war, as they took on male roles, particularly in the metal industries, transport and the civil service. The effect of this work on female behaviour was noted in an article on the ‘Future of Courtesy. Women’s New Place in the World’ in The Times on 25 August 1916: “The young woman of to-day likes to look her best; but she also likes to be capable, active and self-supporting.”

Maybe this liberation from old behavioural norms led to the use of ‘flapper’ — originally used for “a young wild duck or partridge” — for confident young women. Or, the term might have derived from teenage girls wearing their hair in long pigtails tied with large bows that flapped in the wind — before adult womanhood necessitated them putting up their hair. Flappers were said to be frivolous, fast and flirtatious, obsessed with having a good time and with clothes. In 1927-8, the Daily Mail railed against lowering the female voting age from 30 to 21, calling it the ‘flapper vote’, thankfully to no avail.

Now

that we’ve cleared that up, let’s open the first chest of drawers.

Laying ‘up’ the foundations

Throughout the 1910s various bra-type garments were in circulation, known sometimes interchangeably as brassieres, bust-bodices and bust supporters. Even earlier versions were more like camisoles or vests with vertical boning to create a ‘monobosom’. The new decade saw the introduction of “bandeaux”, wide stiffened bands with shoulder straps used to flatten the chest. The ‘modern’ bra with its two distinct triangular pieces of fabric or cups, sometimes credited to Caresse Crosby, did not come into wider use until the end of the 1920s. Until then, your foundations would start with a camisole and knickers, which could be combined to create — you guessed it — ‘camiknickers’!

‘Corselettes’ and even corsets remained part of the female wardrobe, but usually bore scant resemblance to the ‘hourglass’ or ‘S-bend curve’ shapewear of earlier times. If you did not want to rely on garters, corsets’ appendages were useful to hold up stockings while tights were not yet in wider use (although worn by stage performers). Made of cotton, or real/artificial silk, stockings were prone to wrinkles but absolutely had to be worn — going out with bare legs was inconceivable!

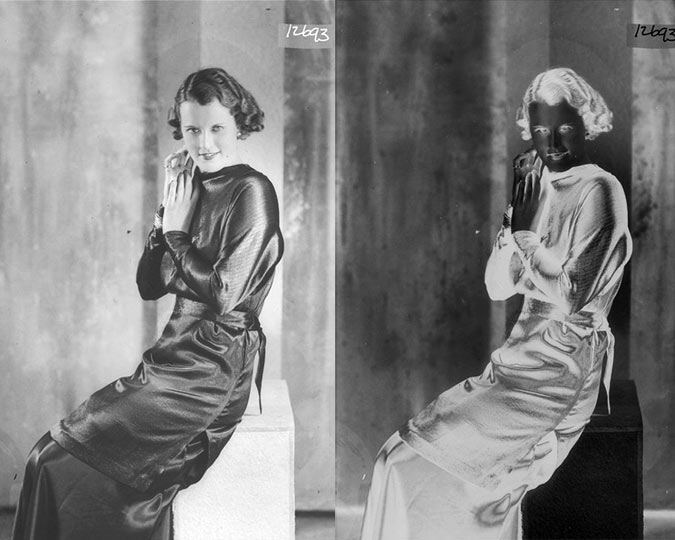

Model showing off her Eton crop as well as eveningwear and outerwear for Vaus and Crampton, 1925 (Bassano Studio, IN10903).

Frocks for all occasions

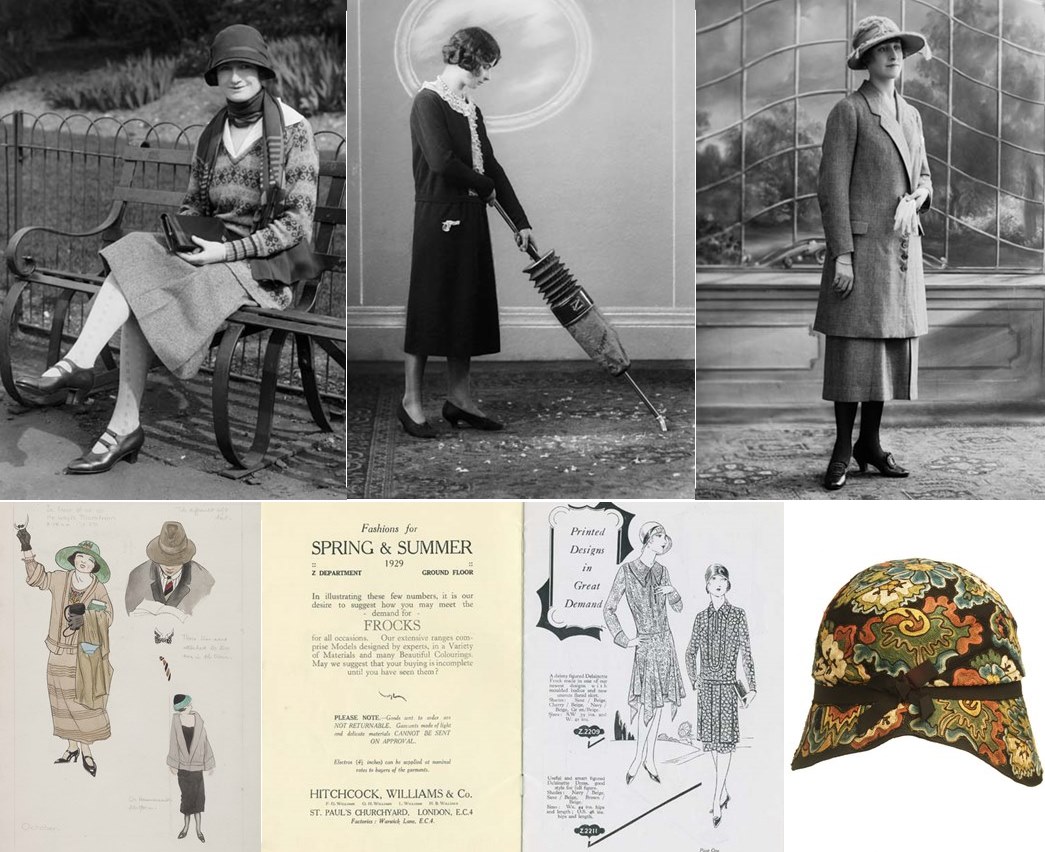

The components of daywear did not change during the 1920s, but what did change was the hemline. This had been creeping up since the beginning of the war and continued to move upwards until around 1927 — usually the year people have in mind when they think of 1920s fashion. The straight silhouette, another feature of what we now consider to be the “look” of the 1920s, actually began a little earlier, with more loose fitting garments emerging around 1918. Ten years later, skirts and dresses started to grow longer again, as well as more figure-hugging, ushering in a new style.

You could put on a one-piece ‘frock’ or a skirt and blouse/jumper combination, bearing in mind that to achieve the low waistline popular for most of the decade, blouses had to be worn on top of skirts. Outside, dresses were covered with matching or contrasting jackets and coats, often lined and/or trimmed with fur.

Between the wars, fur was so in vogue that “summer furs” were worn during the warmer periods. Suits were another popular choice, their jackets getting shorter as the decade progressed.

In the 1920s, the main change in daywear was the hemline, first shorter and then longer. Hats were still mandatory when leaving the house. Most associated with the decade is the ‘cloche’ shape, but wide-brimmed ones were also worn. (ID nos., clockwise from top-left): IN11141; IN10870; IN5078; 64_119_5; 84_291_13_a; 78_157_1_vb)

Into the night

Until the latter part of the decade, the relatively simple dress shape with its straight lines provided a perfect canvas for spectacular embroidery executed in beads, sequins, spangles and rhinestones on plain silk, georgette or metal fabrics. Dresses often included dangling parts such as fringing that would have moved and caught the light when moving. And, yes, this is what is usually evoked by the term ‘flapper dresses’ — worn not just by young women, but everyone who could afford them.

Not every 1920s dress was straight. Another popular style was the ‘robe de style’ or ‘period dress’, so-called as with its wide hips it resembled the side-hooped gowns of the 18th century. The design was associated with the French couturier Jeanne Lanvin and seems to have been more popular in Paris than in London.

Luxurious evening coats were often made in fabrics brocaded with metallic threads, trimmed with the ubiquitous fur. Often these coats did not have any or just one or two fastenings so had to be held close by the wearer, framing her face.

Bobs and Eton crops

In 1920, F. Scott Fitzgerald published his first collection of short stories, Flappers and Philosophers. In ‘Bernice Bobs Her Hair’ the eponymous heroine is persuaded by her frenemy cousin to let a barber cut her beautiful long hair much to the shock of everyone around her. In the early 1920s, women often put up their hair at the back but teased out curls in front so it looked as if it had been bobbed. Only in the mid-1920s, did short hair become ubiquitous leading all the way to the so-called Eton crop.

Clothes and manners

On 8 April 1920, the Daily Mirror published ‘Clothes and Manners’ an article about a new play performed in London a few days earlier. Other Times was written by Harold Brighouse who, as the son of a manager of a Lancashire cotton-spinning firm and former textile buyer, probably knew a thing or two about clothes. The improbable plot sees “elaborate manners of mid-Victorian days” contrasted with “slangy, jazzing young England” when “a very modern set of girls and boys” are stranded on a remote Scottish island (Daily News, 7 April 1920). The young women have to make do with the Victorian clothes of the resident Colonel’s late wife, which effect their behaviour: “You may think you know what to think of the lightly clad flapper as you see her light clothes. But then you may easily reform her if you put her in a crinoline. […] Her movements will be different, and those will alter her manners. You cannot Jazz in a crinoline.”

PS: Before you accuse us of ‘decade-ism’ (yes, that is a thing), we know that fashion changes do not neatly occur at the beginning and end of decades or centuries, and that 10 years of fashion history cannot be summed up in a thousand or so words. In this and future posts, we will focus on what we can glean from the museum’s collections, and not just those kept in the Dress & Textile stores, as there are fashion-adjacent objects in every department.

Love fashion? Subscribe to our fashion newsletter to read more stories from our collections, and find out about upcoming events and exhibitions.