|Year: 1948|

Windrush stories

Listen to Lord Kitchener, the "King of Calypso", sing as he disembarks from the Empire Windrush in this rare video courtesy of British Pathé.

[FILM BEGINS]

Narrator: The Empire Windrush brings to Britain 500 Jamaicans. Many are ex-servicemen who know England. They served this country well. In Jamaica, they couldn't find work. Discouraged, but full of hope, they sailed for Britain.

[00:00:30]

Narrator: The Colonial Office gives them a more cordial reception than was at first envisaged.

Reporter: Now may I ask you your name?

Lord Kitchener: Lord Kitchener.

Reporter: Lord Kitchener, now I'm told that you are really the king of calypso singers, is that right?

Lord Kitchener: Yes, yes that’s true.

Reporter: Will you sing for us?

Lord Kitchener: Right now?

Reporter: Yes.

[00:00:46]

Lord Kitchener:

♪ London is the place for me

London, this lovely city

You can go to France or America

India, Asia or Australia

But you must come back

To London city ♪

[00:01:07]

♪Well believe me, I am speaking broad-mindedly

I am glad, to know my mother country

I've been travelling the countries years ago

But this is the place I wanted to know

Darling, London, this is the place for me ♪

[FILM ENDS]

A city in need

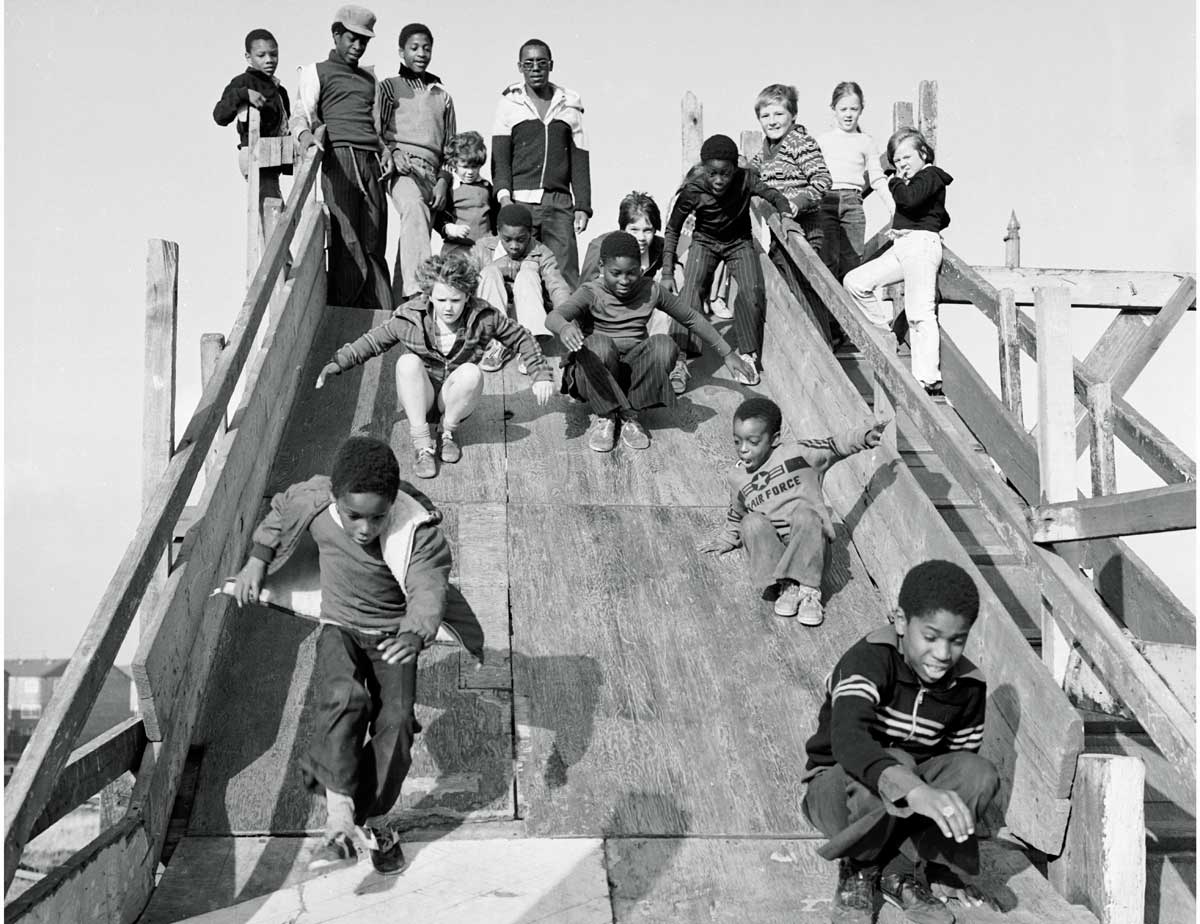

London Transport workers, Crystal Palace, 1963

Several thousand West Indians arrived in Britain

to take jobs as bus and train drivers, conductors and ticket sellers.

© Henry Grant Collection/Museum of London

During World War Two, Britain suffered great damage. After the war, London was in need of care and repair.

Britain needed more workers to fill roles in the railways, the health service and other important industries to rebuild the country.

In 1948, the British Nationality Act gave people from Commonwealth countries the right to settle in Britain as British citizens to help with this work.

The British government recruited people from the Caribbean – Jamaica, Trinidad, Barbados - and West Africa, to come and help put the country back together.

Tilbury Passenger Terminal, 1957

The Empire Windrush docked at this port, bringing the first of the Windrush generation to England.

© PLA collection/Museum of London

One of the first ships to arrive as part of this new wave of migration was the Empire Windrush, on 22 June 1948.

The 802 Caribbean people on board were amongst the first of 500,000 Commonwealth citizens who eventually settled in Britain between 1948 and 1971.

High hopes, harsh realities

People came to Britain with high hopes. Many had learned about the history of the ‘motherland’ at school and felt a connection even from afar. However, many of these new arrivals faced prejudice and unequal treatment, some of which continues even today.

In 1948, the National Health Service (NHS) began. Many women travelled from Africa and the Caribbean to train as nurses in the NHS.

Click the triangular play button below to listen to a Caribbean nurse discuss her experiences coming to London:

Interviewee: The white people that we were caring for, most, they were all white. Very very very few West Indians or Black people as patients.

Interviewer: As patients ah

Interviewee: Throughout my 3 years of nursing. Um, and they were very rude. Very hostile, very rude, very well for want of a better word ignorant about the rest of the world. They didn’t know where Trinidad was. They kept saying what part of America? What part of Jamaica? What part of Africa? What part of Europe is Trinidad?

Interviewer: Yes indeed, indeed. You know you speak with positivity and hopefulness can you give me an example of, well, someone who let’s say was quite ignorant and rude? Who actually changed their mind, in actually getting to know you or can you remember?

Interviewee: yes um. Well, I mean the patients, when I decided to stop crying and to get a grip. Because that was the other thing and it reminded me so much of what Floella said this morning in the lecture. She said you know, about the bullies and her mother talking to her. I used to cry and I rang my mother in Trinidad and I told her this place is awful. It’s cold, it’s damp, it’s grey, It’s dirty and broken down. So much building sites everywhere. And about the people who were so rude and horrible. And I want to come home. And she said “come home to do what?” She said “listen. I did not send you, you did not go to London to like the city or to like the people. You went for a purpose. You are there to study and do better in life so that you could come home and have a rewarding and fulfilling future and make something of yourself. You didn’t go to like people and if they don’t like you that is their problem anyway.” Yeah, she said that, that her mother told her that and my mother told me, well she is Trinidadian too. So that’s how the mothers were. They were strong, independent women.

Interviewer: How did that make you feel? When she said that to you?

Interviewee: Well, quite amazing and it, it you know you start to reflect and think right yes. And then around the same time when I got to grips with myself, not hearing it from anybody else, was when this man, who was in long term, kept calling us monkeys. How are your treehouses? You know, how are your treehouses? How do you get up there? And how do you get around? Donkeys, monkeys, you know? And one day he said something like that or he said you Black something to me. And I said listen. I am sick of you calling me names. I said I am Black. For 21 years I know I’m Black. So tell me something I don't know. And he stood up and he said, what do you mean? I said exactly, tell me something I don't know because I am aware that I am Black for 21 years. And that changed everything for me and for him. He started to ask, you know, more decent questions. Until I ended up taking photo albums onto the ward to show him. I said oh I brought something for you to see. I said have a look while I do my work. And I showed him, you know, that we had cars, we had indoor toilets, we had houses.

- Did anything surprise you about her experiences? Do you think the same thing would happen today?

New communities, new culture

When people migrate to a new country, they also take with them things that are not physical objects.

- If you were to move to a new country, what skills, talents or knowledge would you be taking with you to share with a new community?

Settling down

Some people thought that they would stay in Britain for a few years, earning some money, and then return home to the Caribbean. However, many people stayed and ended up settling for good and raising families here.

Click the triangular play button below to listen to this clip about the importance of appearances at home for the Windrush generation.

Interviewee: Briefly looking at the living room that my parents had, I think so much of it comes down to people wanting to show how nice they are, how genteel they are, how much this is what they we are like, this is what we really have as qualities, unlike what people might think about Black families, Caribbean families, immigrants. In our case we’d never heard of Jim Reeves, I’d never heard of Jim Reeves until I came to this country, so it was funny hearing recently of that being one of the performers that West Indian families liked when they were in this country at least. For us it was very different but nevertheless we still had tailor-made plastic coverings in the living room and no one was allowed to sit there unless visitors came, we didn’t really live up there, it was for show, it was ‘the good room’, and I think that was again to show that this is how we really are, these are our values, this is the good room, we are nice people, and as I say I think a lot of it is down to colonialisation, to slavery, and to knowing ourselves to be better than we are thought by those outside, wanting to show at least in this one space that was our own.

- What might people's hopes have been for their new lives?

Caribbean people not only brought their skills to London, but their culture as well.

- Are there clothes you wear, food you eat or music you listen to that is influenced by Caribbean culture?

Black Londoners through time

Keep on discovering London’s Black history from the Roman era to the present day in our timeline.