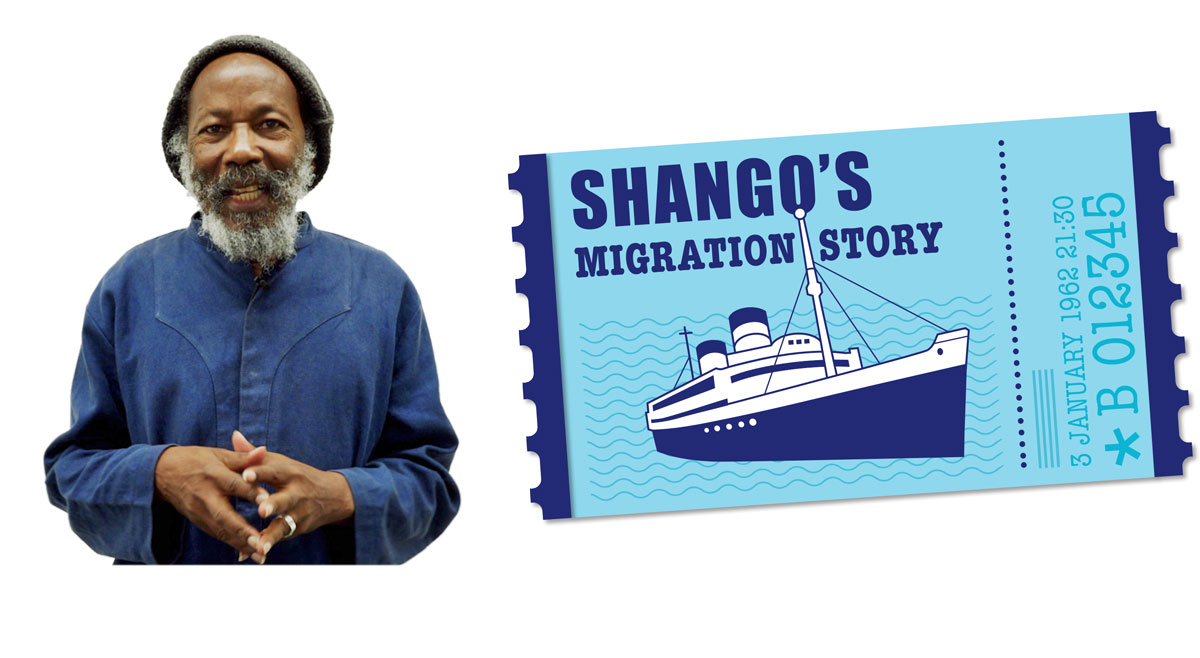

Shango's migration story

Listen to Shango tell his personal migration story as he left Trinidad in 1961 for Britain. Find out about his hopes and ambitions and the realities of life in London during the 1960s as a Black person.

How to use this resource

Below you'll find seven short videos on themes from Shango's experience of coming to live in the UK.

You might like to play these in an assembly or have a classroom discussion using these films and the prompts that follow. Or you could split students into small groups to take a video each, in class or as a homework task.

We recommend students engage with this resource already knowing about Commonwealth migration after the Second World War to Britain, particularly migrants travelling from the Caribbean countries. You might wish to introduce your students to:

- The inaugural journey of the HMT Empire Windrush and why it was so important for Britain and the Caribbean countries

- Why some people might choose to move their life from the Caribbean to Britain

- The 1948 British Nationality Act making all people who lived within the Commonwealth British passport holders and therefore entitled to live and work in Britain.

This resource also discusses the issue of racism that Shango has experienced in his life. You may wish to consider the sensitivities around this before asking students to watch the films.

Scroll through the page to browse the videos and discussion points or click on these links to skip down.

- 1. Growing up in the British Empire

- 2. All aboard the SS Ascania

- 3. Arriving to an English winter

- 4. Living conditions

- 5. Experiencing racism

- 6. Finding community

- 7. Changing the UK

1. Growing up in the British Empire

Shango shares what it was like growing up in Trinidad under colonialism and how he felt about Britain, the 'mother country'.

[SHANGO SPEAKS]

Growing up in the Caribbean we had this notion of a ‘mother country’ that looked after us. We were told that we were British and we accepted that without question. As a matter of fact, in the 1950s at school on special days we sang 'God save our gracious King!'

[00:00:26]

King George was on the throne at that time. And on other occasions he would sing,

[♪ SHANGO SINGS ♪]

'Rule, Britannia! Britannia, rule the waves! Britons never, never, never, shall be slaves.'

[SHANGO SPEAKS]

Sometimes families and friends would gather around a small transistor and listen to the BBC overseas news broadcast every day at 6:00 PM precisely - 'Pip! Pip! Pip!' Or we would listen to the Test match if the West Indies were playing cricket against Britain.

[00:00:59]

This was relayed from Lords or from the Oval or from Edgbaston. We would listen to every ball that was bowled and every stroke that was hit and we'd be glued to that small transistor.

We didn’t have any idea of ourselves as being a separate people with our own identity, and that only came into play in the early 60s, when one by one the British Caribbean islands gained independence from Britain and became self-governing, and then we develop perhaps a sense of self, a sense of our own history, a sense of our own culture, and we learnt more about Africa, etcetera.

[00:01:37]

[VIDEO ENDS]

Discussion starter:

Using your knowledge of the British Empire and the Commonwealth, why do you think Shango uses air quotes around the word 'independence'? What could that mean and what might that tell us about Shango’s opinions towards the ‘mother country’?

2. All aboard the SS Ascania

Listen to Shango recount his stories of new friendships and their hopes and ambitions for their new lives in Britain as they travelled across the Atlantic.

[SHANGO SPEAKS]

You know travelling away from the island to Britain you meet different people on board a vessel like the SS Ascania - an Italian liner - and you make friends.

I still remember them, there was this light skin Trinidadian called Vin Cardinal. He was a musician, play the vibraphone very well and he joined the ship's musical band the minute he came on board. And there was this tall, dark fellow. He was also from south Trinidad. Joe. And we have oil in Trinidad:

[00:00:40]

Joe had worked as a seaman on oil tankers delivering oil to all parts of the world - the Middle East, the Far East, India, etcetera - so he had a lot of tall tales to tell. And there was this giant of a guy called Scotty. Scotty was a gentle giant. He would go to great lengths to apologise if he felt that he had offended anybody by something he said or by his size - he was very aware that he was big and broad.

[00:01:07]

And we spent hours discussing what we would do when he got to Britain because we’d heard of so many people who had gone to America, gone to Britain, gone to France and parts of Europe and made a name for themselves and we were following in their wake. We had great expectations.

[00:01:25]

[VIDEO ENDS]

Discussion starter:

At 18 years old Shango travelled on his own from Trinidad to meet his family who were already living in London. How do you think Shango felt travelling on his own? How might you feel? What would your expectations be travelling to a new country?

3. Arriving to an English winter

After arriving in the middle of winter, hear about Shango's memorable first few days in the UK, his shock at the new climate and getting used to life indoors.

[SHANGO SPEAKS]

We didn't arrive before Christmas as expected. As a matter of fact we spent Christmas and New Year’s on the high seas, the Atlantic, finally arriving at Southampton on the 3rd of January 1962.

[00:00:20]

My father who was a Trinidadian civil servant, studying in Britain for a six-month period, came to Southampton to meet me with this great big coat. I could wrap it around myself twice, three times and still have space inside of it And we took a late night train ride from Southampton to Waterloo.

[00:00:41]

And that's a ride I'll never forget. Looking out of the shutters as the train sped through the open countryside I could see this strange, white snowscape. Trees without leaves with snow hanging off the branches and this eerie feeling of cold. Nothing can prepare you for it and it felt as if I'd been transported into a nightmarish world, something that I'd never experienced before.

[00:01:10]

The complete opposite of our life in the tropics. Instead of spending all those days out of doors, suddenly we were restricted to being locked down indoors having to perhaps find different ways of enjoying ourselves or making life inside rather than out of doors.

[00:01:32]

[VIDEO ENDS]

Discussion starter:

Shango experiences his first views of Britain as being very different to Trinidad. Can you think of a time when something has appeared negative to you, only because it is unfamiliar?

Stretch question: Do you think we can use this example to explain some Londoners' hostility to immigrants, or does it go deeper?

4. Living conditions

Shango reflects on his own experience as he joined his family in Chiswick and the difficulties that his friends faced when they tried to find a place to live.

[SHANGO SPEAKS]

The Colonial Office had prepared a place for people like my father, who were there for a short stay to do a course of study, and also his family.

[00:00:17]

We were well housed in a residential area of Chiswick. We occupied the top room of a two-storey building and I remember this large basin that we used for baths. Filling it up with kettle after kettle of hot water and then adding some cold.

[00:00:38]

Toilet facilities were around the back of the house so if you got caught, suddenly you had to wrap yourself, be warm, do what you had to do very quickly, come back into the paraffin-heated room. But we were well taken care of.

[00:00:54]

Others who I came up with like Scotty, Joe, Vin... When I met them years later, they told me of the terrible problems they had in finding accommodation because landlords were afraid to anger local residents by bringing immigrants into the area, who they weren’t accustomed to seeing and so they impose a curfew sometimes that you had to leave the house at eight in the morning, come back in after six so that your presence wasn't felt in the surroundings and some had to sleep on the Underground during the night, look for jobs during the day.

[00:01:31]

Others rented one small room, a bedsitter. One would work the day shift, another would work the night shift and they would share this sleeping accommodation and pay one price for the rent of it.

[00:01:43]

So it was difficult for some, who were not as lucky as I was to have a place ready to accommodate them in Britain.

[00:01:52]

[VIDEO ENDS]

Discussion starter:

Having watched the video and heard about the experiences of the friends Shango made on SS Ascania, do you think Shango was fortunate to have the start in Britain that he did due to the work placement and accompanying housing his father had secured? Who was better prepared for life in London: him, or his crew mates?

5. Experiencing racism

Shango remembers a hostile encounter on his journey home from a cricket match and how this was a wake-up call to the realities of prejudice in the UK.

[SHANGO SPEAKS]

Probably three months after I arrived in Britain, I had joined a cricket club playing in Turnham Green on weekends and I remember taking this catch on third slip and being applauded by my colleagues and people in the stands etcetera.

[00:00:20]

It was very enjoyable. The grounds were immaculate, the players were well behaved. Everything was very easy going. We had tea and scones in the clubhouse at 6pm and started the second part of the match after that

[00:00:36]

I was coming home from Turnham Green by Tube one evening, and as I stepped out of the Tube at Stamford Brook, which was 500 yards away from where we lived, I was accosted by these four or five young thugs who grabbed me up and pushed me against a shop front and threatened me with a good beating if they ever saw me in that area again. And I was so taken aback that I didn't offer any resistance, I was just wondering what I had done to deserve this.

[00:01:07]

Fortunately I didn't get harmed, I don't remember being hurt but this was certainly a wake-up call where suddenly I realised that, you know, London was not as safe as I thought it was.

[00:01:19]

It could be hostile when it became dark for a lone Black person walking the streets. And I learned that these Teddy Boys were gangs that roamed London. Young, white, youths who were generally unemployed and looking for aggro, as it were, and if you were in the wrong place, at the wrong time you could find yourself in a lot of bother.

[00:01:44]

So from that time I remember being much more careful how I carried myself.

[00:01:50]

[VIDEO ENDS]

Discussion starter:

This is one of the experiences Shango had in London that he describes as a ‘wake-up call’. Having watched Shango recount this story and describe London as ‘dangerous for a lone Black man,’ how do you think this would have made Shango feel?

6. Finding community

After leaving the Civil Service in the 1960s, Shango found a new sense of belonging in the Black community by joining the Rastafari movement, which he continues to be involved with today.

[SHANGO SPEAKS]

I left the civil service in the late 60s. You know there was a wind of change going through the Black community not just in London but I think worldwide. You had Black Power in America and the Caribbean and it touched Africa as well and it certainly influenced us here in Britain - that we needed to find some sense of identity, some sense of belonging.

[00:00:29]

And I was influenced to join the Rastafari movement, on the fringes of it at first, and then I joined a group of Rastas who were actually part of the Nyahbinghi National Committee. And after some years I became a writer dealing with a magazine that was produced by this group, which I still adhere to, and this was something that gave us a feeling of self. A feeling of being original Africans, from the continent of Africa, and being more or less in exile from Africa, so the themes of repatriation and reparation were things that we dealt with and still deal with.

[00:01:14]

So it was a community of similar thoughts, similar feelings, not necessarily antagonistic but having to work our way into the society in ways that was acceptable, that didn't make us feel demeaned or less than who we were, and a lot of young people at that time became Rastafari because it offered them that sense of self, I think.

[00:01:43]

And to date, I'm still a member of that movement generally. I am a Rasta basically.

[00:01:50]

[VIDEO ENDS]

Discussion starter:

There are large African-Caribbean communities in Notting Hill Gate, Shepherd’s Bush and Brixton today with a vibrant and important cultural scene. Is it more important that communities stay together, or would it have been better if immigrants had found housing all over London? What gives you a sense of self and belonging?

7. Changing the UK

Shango shares how he thinks the Windrush generation paved the way to make the UK a more multicultural and tolerant place today.

[SHANGO SPEAKS]

You know in life, generally we are influenced by those who come before us and who open doors that we can go through. And it's only in coming to Britain that I realised that the Windrush generation began changes in Britain that afforded it a much more multicultural outlook on life.

[00:00:28]

For instance the biggest street festival, the Notting Hill Festival, was started by us importing that carnival here, and the steel bands, etcetera, and now it's the biggest street festival in Europe.

[00:00:41]

It seems contradictory that that small island that we didn't consider great has impacted, the Caribbean itself, has impacted on Britain in a way that has made it open up itself to acceptance of many different races, many different cultures.

[00:00:57]

You know, when you go to schools like yours in London, we see so many nations, sometimes we go around and say, 'Where are you from? Where are you from?' and people have ancestors in Greece, in Romania, in Venezuela, in India, all parts of the world are here today.

[00:01:16]

So, we tend to say that that's a great experience for you to grow up in that multicultural environment because you learn from each other and you become citizens of the big world, you become educated in a way that more than just subjects can educate you. But knowing different people from all parts of the world is an education, where you can be tolerant of everybody and be knowledgable about people and find a place in the world that is yours particularly but also belongs to everybody else.

[00:01:52]

[VIDEO ENDS]

Discussion starter:

Can you identify any other ways that the arrival of the Windrush generation has impacted London?

Shango challenges you to become ‘citizens of the big world’. What do you think he means by this? How might you be able to achieve becoming a ‘citizen of the big world’?

Windrush stories

Visit for more history on the African-Caribbean community in London including oral histories, articles and our extensive photography collection.

These pages were not created with a school audience in mind and the content might be sensitive for younger students.