A new display at the Museum of London, Revealing the past, gives a conservator's-eye view of our collection, uncovering hidden details on archaeological objects.

We set up our Looking for Londoners gallery to give us a space to focus on our archaeological collections. Our most recent display, Revealing the Past, looks at the work of the museum’s archaeological conservators — the staff who preserve and protect excavated objects, making them ready for display and keeping them from further decay. Over the years we’ve worked on thousands of objects and have discovered fascinating details only visible under the microscope — details this exhibition reveals to our visitors.

Conservation is crucial to any institution that collects and preserves cultural heritage. Most large museums have a team of conservators, sometimes specialists in particular materials or areas such as collection care. Small museums may not have a conservator on staff or may have just one conservator with general conservation knowledge, and call in specialists when needed.

Medieval leather boot

ID no. BC72_250_3698

The museum has a vast archaeological collection of 6.2 million items, so within the conservation team there are three archaeological conservators, working alongside three conservators who work on newly excavated material for Museum of London Archaeology (MOLA). With so much archaeological material in our archive and a regular flow from current excavations, we have the opportunity to examine and conserve fantastic individual finds in our conservation lab. This includes large quantities of wood and leather objects preserved on waterlogged sites. Extremes in burial conditions can preserve these materials: very dry environments such as those found on desert sites, very cold, frozen soils or wet muddy conditions. As would be expected, in London it’s the latter – well-sealed wet conditions. These occur along the Thames, its tributaries and in waterlogged deposits such as wells and cesspits. The wet conditions mean that there is no air to dry out or corrode objects, and protect organic materials from decay.

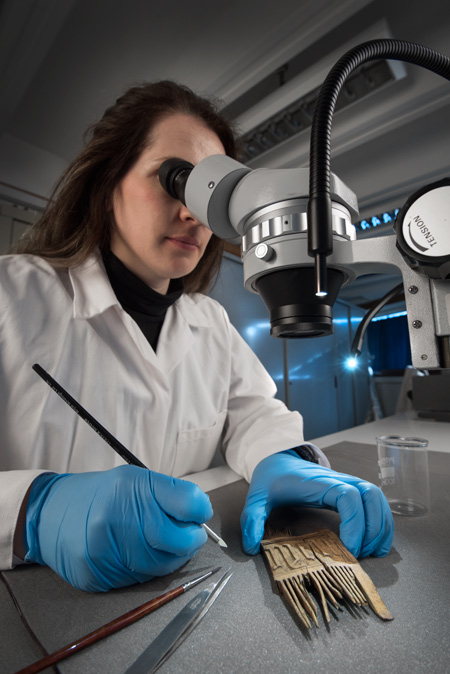

A conservator examines a boxwood comb

Examining an

object is the first stage of all conservators’ work; for archaeological

conservators there is an added dimension as some material will have been

affected by centuries of burial. A

microscope is the key tool for an archaeological conservator; we spend hours at

the microscope looking at layers of corrosion or removing soil from a surface. We

have to be careful in case other materials are hidden or preserved within the

soil or corrosion, giving us clues as to how an object was used or decorated.

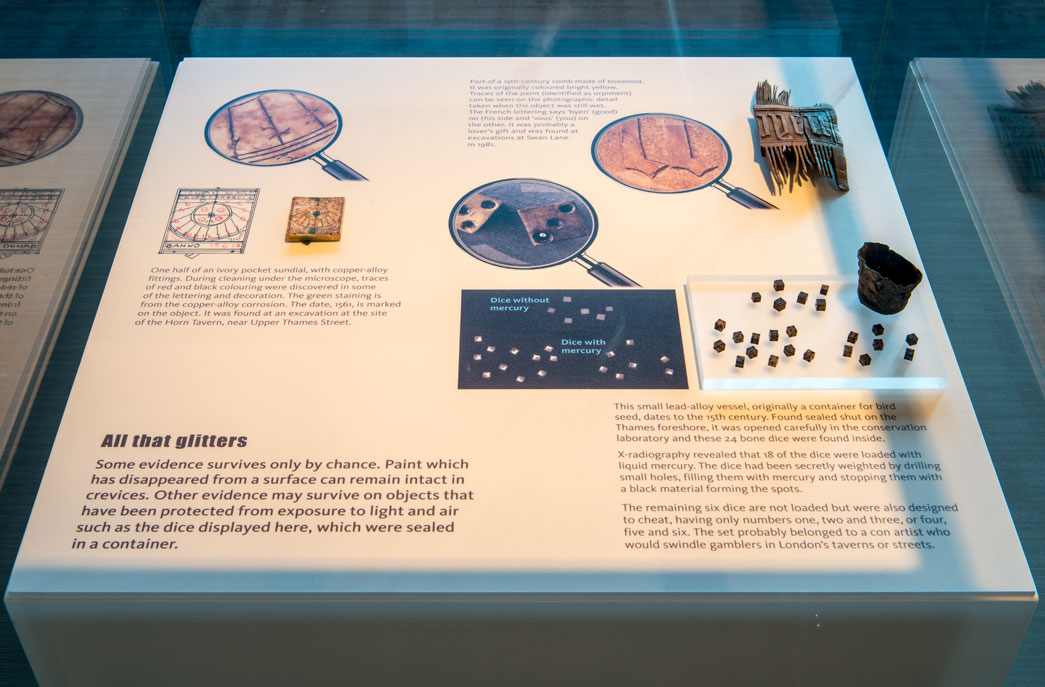

For the display we wanted to select objects that demonstrate this but it is challenging to show microscopic detail. Magnifiers in showcases can be tricky – allowing for different types of vision is always a problem and sometimes the magnifying glass obscures the object you want to show. A digital display such as a tablet would have been ideal. But for a two month display we needed something low tech and effective.

Our graphic designer suggested using an image of a magnifying glass with a photograph of the detail reproduced next to the object. It was just right for the objects displayed, showing close-up details which normal visitors to the museum would never get to see.

This 15th-century boxwood comb is a good example. It would have been coloured bright yellow when first made. Traces of yellow paint can be seen on the photographic detail taken when the object was still wet. The paint stayed in the small pricks in the surface that were used to prepare the surface of the comb. The paint is still there but is not as visible now after conservation treatment to dry the object. Interestingly, in the 14th century Paris craftsmen were forbidden to paint and gild combs as coatings could flake off during use. This was a wise precaution considering that some paints were arsenic-based. We've identified the yellow pigment used on this comb as orpiment, an arsenic sulphide.

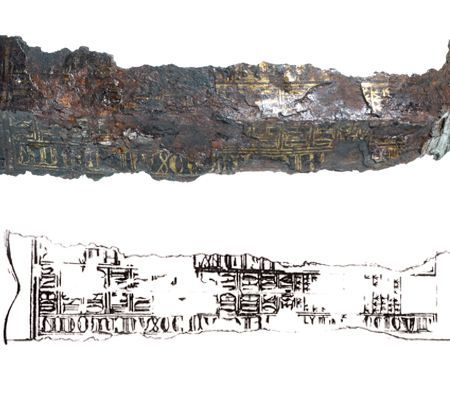

Another example of rare survival and close examination is this 15th century iron sword found in 1983 during the final stages of excavations at the site of the Billingsgate Fish Market. It is very unusual to find a complete sword from an excavation. Although corroded and bent out of shape, we could tell immediately that within the corrosion lay something even more special – traces of gold. Archaeological iron normally corrodes so much during burial that anything on the surface is lost or badly damaged. Iron from London’s sites along the waterfront is often preserved in good condition so some coatings survive, but these are mainly made of tin. The gold we found on this sword was not just a coating but lettering.

There is quite a bit of it remaining on both sides but only one word has been deciphered (DOMINUS – ‘Lord’ in Latin). The gold was analysed with a scanning electron microscope and showed the presence of mercury which gives a clue to how it was applied. We also know the sword had a hilt made of wood (identified as beech) and tiny traces of leather found while examining the object indicate that it may have been enclosed in a leather sheath. There are many highly decorated swords in good condition in museum collections around the world, but there is something very special about finding one with just traces of its former glory hidden within soil and corrosion.

These are just two of the objects archaeological conservators have found with traces of the past. One of the joys of this work is looking through your microscope and never knowing what will come up next.

The Revealing the Past display at the Museum of London closed 25 June 2017.