Explore what defines a rare book, from age and editions to owners’ notes. Here are tips on storage, deterioration signs and safe handling techniques to preserve these literary artefacts.

As a museum, we often get questions about whether certain books are rare, or how to take care of special books in personal collections. And let’s not forget the big question – when to wear gloves when handling special books?

The ‘older is rarer’ philosophy may not be the only deciding factor in determining a book’s rarity. Whether you're a collector, an enthusiast, or a curious reader, understanding what makes a book rare and how to preserve it could be helpful. Here we answer some of the most commonly asked questions on books and book care.

What qualifies as a rare book?

Age, availability, ownership and condition are some of the factors that help decide whether a book is rare or not. Medieval manuscripts and books printed before the 1500s (known as incunabula) are historically rare and automatically treasured. The Museum of London Library has one such book, a 1478 edition of the Postilla in Epistolas Pauli, also called Epistles or Letters of Paul – the earliest printed book in our collection.

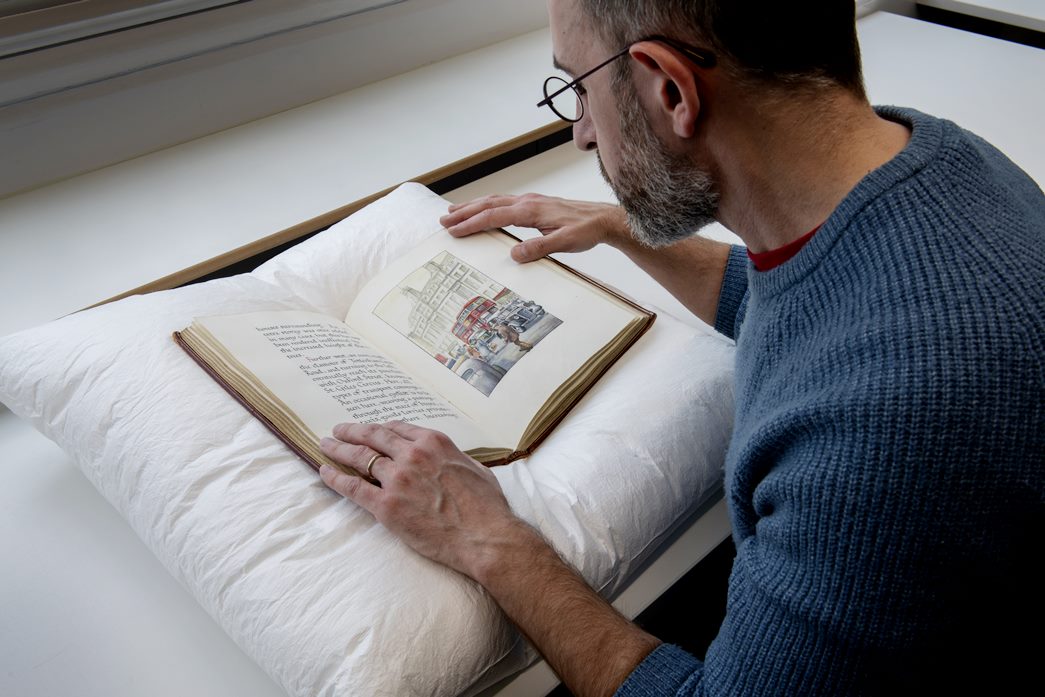

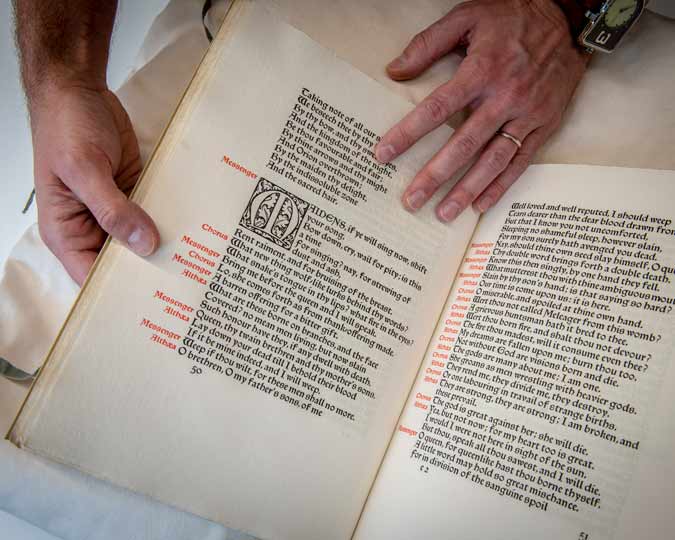

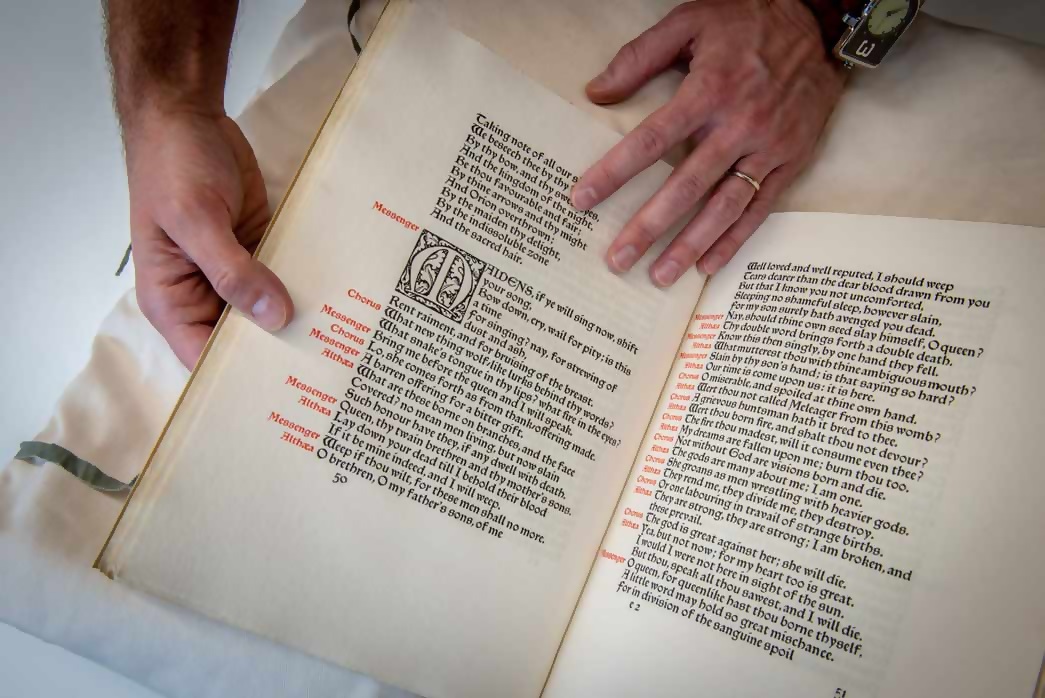

AC Swinburne’s Atalanta in Calydon: a tragedy

One of the volumes published by William Morris, an example of medieval revival. (ID no.: 56.194/50)

How can I identify if a book in my possession is rare?

The easiest way to understand how rare a book may be is to investigate how many copies of the book may have survived. A good start is to check combined library catalogues such as Library Hub Discover (UK and Ireland libraries) or WorldCat (international collections). If you own an early printed book, check which edition it is. Imprints may have very subtle differences and these will be key to assessing their rarity. Records on ESTC, for example, often describe what differentiates one edition from another.

As was the case with the 500 copies of the first edition of Harry Potter and Philosopher’s Stone, print mistakes ended up increasing the value of the books. One of them sold for around £75,000 at an auction in 2020.

What lesser-known factors contribute to the value of a rare book?

Alongside age and edition, ownership, donation or dedication inscriptions often contribute to the value of a book. Ownership can also be traced from bookplates, these are printed labels usually attached inside the book’s cover.

A book may have handwritten notes or drawings – often referred to as ‘marginalia’ – that can be a great source of information about who its previous owners were. Some of the Museum of London’s almanacs and pocketbooks are rich in marginalia, which add to their value as documents of social and personal history.

From inside to the cover – yes, we’re talking about judging a book by its cover. Check if yours has the original binding. Early book collectors often favoured rebinding volumes, which means many old books no longer have the binding they were manufactured with. An original binding, whether in sober leather, parchment or cloth, or heavily decorated with metal, intricate designs or even embroidery could add to the value of the book.

Should I get my rare books appraised, and how do I find a reputable appraiser?

The

antiquarian book trade sector is the best port of call for advice on the

financial value of a book. Early printed books or lavishly published volumes

are often priced high. However, as we have seen, books can tell more than the

story printed on their pages, so aspects like past associations or historical context can make mass-produced volumes like

Bibles or pocketbooks not only significant but museum-worthy items.

How should the books be stored?

Books are best kept in rooms with stable temperature and humidity levels. So, garages and lofts are not ideal locations. Consider your living room or spare bedroom instead. Be sure to always keep them away from light and heat sources (like windows, radiators or a fireplace).

Some people like to arrange books by colour, but while this makes for a beautiful display, it doesn’t necessarily mean that the books are well-supported on the shelf. For rare and special books, arranging them by size will support them better. Large volumes are better stored flat, while small and medium books will be happy upright. Large books stacked horizontally can also do the work of a book-end next to a row of smaller books.

Dust settling on the tops of books is a source of acidity, and could cause foxing (browning and spots on old paper) as well as other biological activity that degrade paper. A clean soft brush such as a large blusher brush which has never been used for make-up is perfect for brushing dust off the top of books.

What are the common signs of deterioration in rare books?

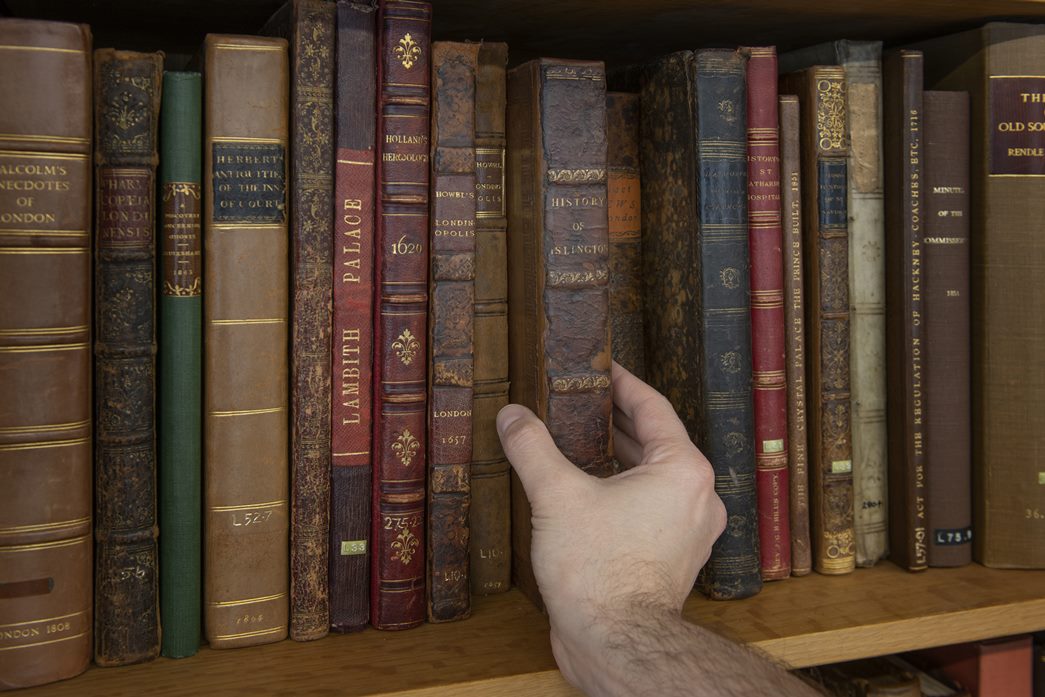

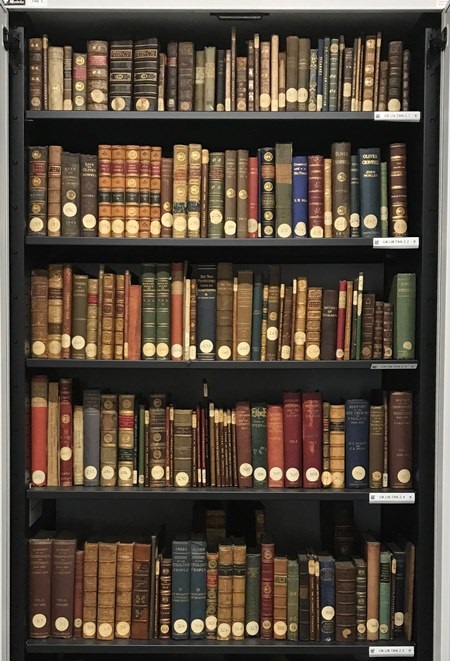

The Tangye Collection in store at the Museum of London Library.

If the pages of your book are disintegrating, it is likely to be made from wood pulp paper and the pages can be as fragile as an autumn leaf. You could wrap it in acid-free tissue paper, or inside a box, for stability. It’s always a good idea to label the box or wrapping clearly so that you can easily identify the book from the outside without needing to handle it.

Similarly, for leather bindings that might have ‘red rot’ or something else affecting their condition, it’s advisable to keep the book in a box so that the powder coming off the book does not spread to other items in your collection.

Importantly, don’t be tempted to do your own book repairs. Old cello-tape repairs or other inappropriate materials used on broken books can cause much worse problems in the long run and they can be costly to reverse. At the museum, we send our books for specialist treatment, and you can find an accredited book conservator near you using the Conservation Register.

Are there special handling techniques for rare books?

Changing the way we remove books from shelves is the best way to prevent damage to the headbands of hardback books. If there is a small gap behind your row of books, you can push the books in on either side of the book you want. Then, put your hand around the book in the centre of the spine and pull. This avoids putting tension on the top edge of the book.

If you do find that you have a loose part in your book, such as a broken cover, you can use canvas tape to tie the book so that parts are not lost. Medical crepe bandages can also be used as a conservation ‘first aid’.

When handling large, heavy books, use two hands and find a cushion or other support to keep the book on. Sometimes, opening a book flat on a surface can potentially damage the spine.

Should I always wear gloves when handling my special books?

It’s not necessary to wear gloves when handling books, but it is important to wash your hands so that they’re clean. If you suffer from cracked skin in cold weather, wearing well-fitting nitrile or vinyl gloves might be a good idea.

In some cases, wearing gloves can also protect you if you suspect the book you have might contain hazardous materials such as bright green arsenic pigments that were common in the 19th century. It’s important not to handle objects while wearing hand cream. And whether your hands are gloved or not, don’t touch your face before handling the book, or lick your fingers to help turn the page for your own health as well as that of the book.

Rare books are more than literary artefacts. They are unique windows into the past. By understanding what makes a book rare and how to preserve it, we can safeguard these treasures for future generations to enjoy.

Header image: Sermons by Guilelmus Peraldus, a 15th-century copy from the Museum of London’s special collections. (ID no.: 46.78/1)

Would you like to get more such insights? Subscribe to our free History of London newsletter for stories from our collections, displays and exhibitions.