Second only to the Bible, in terms of publication, almanacs and pocket books were the main source of handy, relevant information in Europe — from the 16th to the 19th century.

What’s an object that tells you the weather, important dates, transport fares, tide timings, party hot spots, seasonal flowers, bank addresses, gives you space to take notes, AND fits in a tiny little pocket?

We would completely understand if your answer was a ‘smartphone’.

But what if this item had to do all of that between the 15th and the 19th centuries? (The first smartphone was invented in 1992.)

The answer, then, would be: an almanac or pocket book.

The museum has a collection of over 250 English, French and German printed almanacs and pocket book.

The museum has a collection of over 250 English, French and German printed almanacs and pocket books, mostly — but not all — from the 18th and 19th centuries.

Maybe not haute literature, almanacs and pocket books were, however, packed with social and cultural history. Replaced annually to hold the latest information, many have survived — often containing financial records and other memorabilia — with bits of handwritten personal notes. The preface to The Ladies’ Complete Pocket Book (1806) actually encouraged the owner to carry the volume at all times, in order to ‘make Minutes of all Monies Receiv’d and Paid’. It also suggested keeping the volumes after the year had ended, for later use. Contrary to its earlier versions, which would be discarded in December; “used to light a fire or tossed down the privy”!

So, what are almanacs?

An almanac is an annual reference publication/calendar containing important dates and statistical information, such as astronomical data and tide tables. For instance, the 1794 London Almanack in the museum’s collection lists the high tide timings at London Bridge. Probably not significant to the modern reader, this information would have been crucial for those navigating the Thames, since at the time, London Bridge was the farthest point to which tall-masted vessels could navigate up-river. Furthermore, the bridge’s 19 piers had a direct impact on the tide’s ebb and flow, creating dangerous rapids better avoided. It was then advised to leave boats, walk around the bridge and board a new vessel on the other side. Reverend John Bray in his 1670 Book of Proverbs wrote that the bridge was “for wise men to pass over, and fools to pass under”. The wise undoubtedly carried an annual almanac in their pocket!

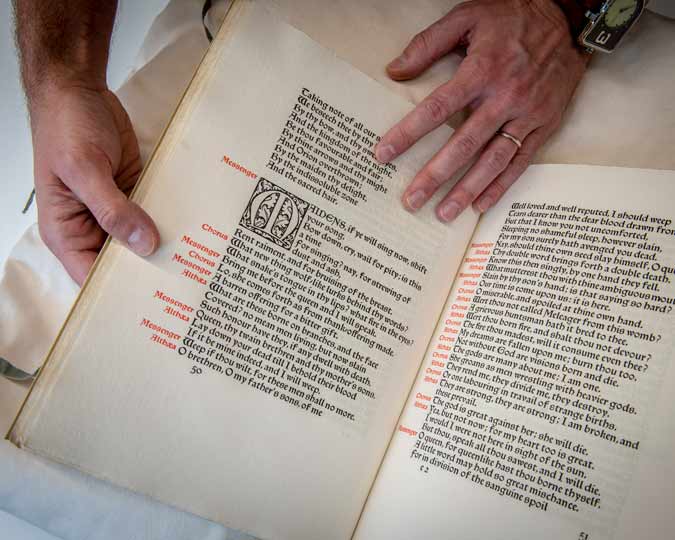

The first printed almanacs were produced in Germany in the 15th century. Two centuries later, they had become so popular and indispensable that in places like England, they were the second bestselling book after the Bible! One of the museum’s oldest examples from 1585 is actually a printed section at the end of a Bible — religion and early science brought together in the name of practicality. In fact, almanacs are now considered the first examples of mass-produced publications.

Universal information

Historically, almanacs have covered a variety of topics, depending upon who they were published for. The most popular would advise the general reader on sunrise–sunset times, moon phases, tide timings, travel time between towns, holy saint days and market days, or public holidays. Many even included a section on prognostication, with predictions on seasonal ailments, etc. The ones from 16th–17th centuries had a fair bit of astrological information too.

An almanack and prognostication for the year of God, 1642

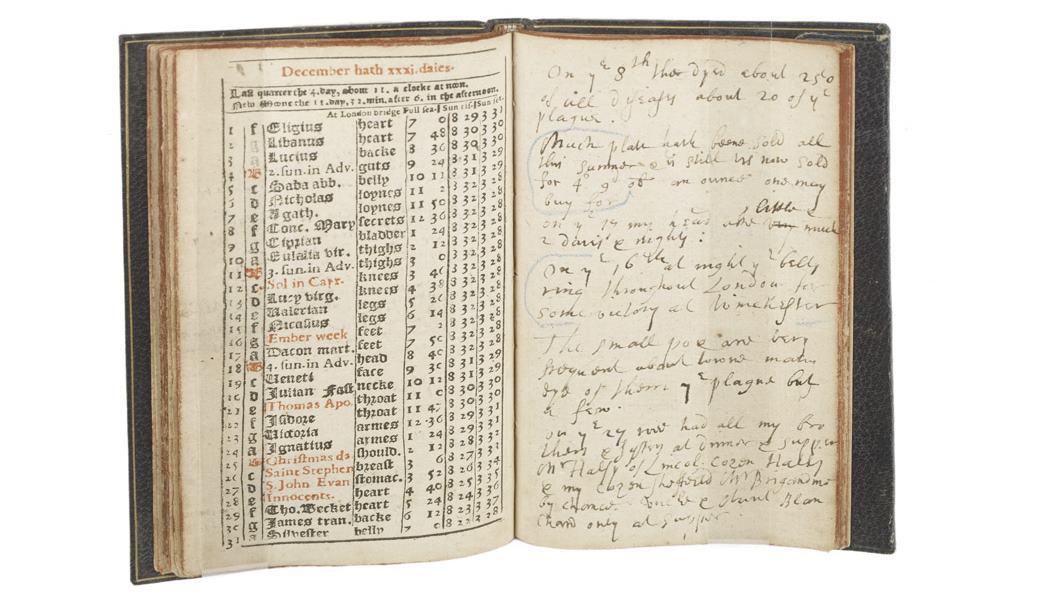

The owner of this almanac records his own state of health and the weekly total of plague deaths in 1642. The ‘pestilence’ was an ever present threat in London: in the 17th century epidemics had already struck in 1603, 1622 and 1636. (ID no.: 46.78/735)

Another example of an early almanac is on display in our War, Plague and Fire gallery. An Almanack and Prognostication for the Yeare of God 1642 was published at the beginning of the English Civil War (1642–51), during one of the many episodes of plague in 17th-century England. Where space was available, the owner recorded his own state of health and the weekly total of plague deaths in that year. His handwritten notes also cover political issues during this period of the revolution.

Making it personal

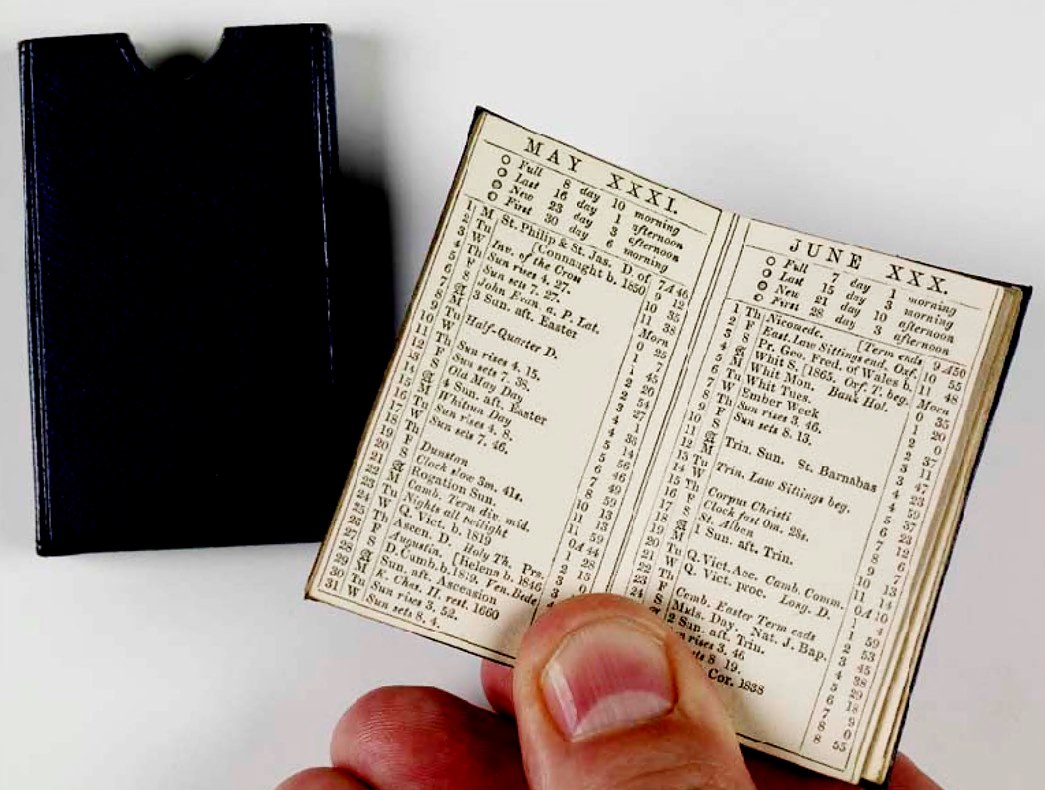

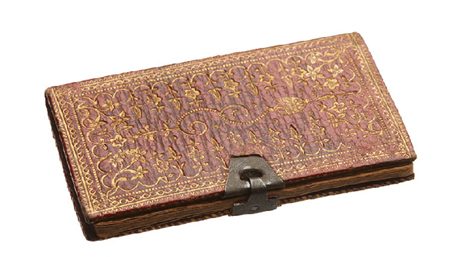

A miniature London Almanack for 1785. (ID no.: NN24336)

By the mid-18th century, almanacs as pure information booklets had given way to pocket or memorandum books, with more space for personal notes. The museum’s collection mostly consists of these integrated books. Meant to be always kept on one’s person, these almanacs and pocket books were quite small so they could be kept in vest and dress pockets — making them easy to consult and write on. Miniature editions (also known as ‘vest pocket’ editions) — like the Company of Stationers’ London Almanacks — range between 3 x 3 and 6 x 3 cm, making them easy to transport but very challenging to read. Even with modern spectacles!

Miniature volumes were printed sideways so months or tables would fit two pages without interruptions.

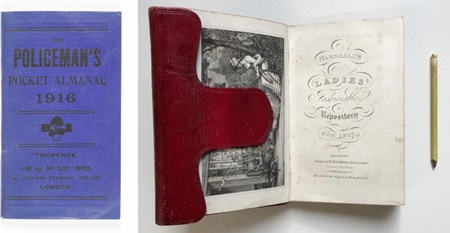

Even if small, these pocket books included appealing illustrations, usually of new buildings, countryside landscapes or the latest fashions (of the year just gone, not forthcoming). These were often by well-known professional artists. They also had attractive bindings, slipcases, and were made of expensive materials like marbled paper, leather binding, flaps with silver clasps, etc. Some were designed with inner pockets to store letters, bills or money; others, like our 1827 copy of Marshall's Ladies Fashionable Repository, included tiny pencils held within the binding.

The Victoria Miniature Almanack and Fashionable Remembrancer for 1847 includes a list of London bankers, an article on Belvoir Castle, ‘The Ball Room Guide’ and ‘The Language of Flowers’. It was priced at just “Threepence”, which was equivalent to buying ‘4lb loaf of bread’ or ‘6 pints of milk’ around the same time.

A regular clientele

The Policeman’s Almanac for 1916 (ID no.: 32.57/10), and an 1827 pocket book with an ivory pencil (ID no.: 2002.139/33)

The publishers of these almanacs/pocket books were well-known, with each catering to a particular clientele. In the museum’s collections, we have examples of 18–19th century almanacs produced for bankers, mariners, policemen, etc. — each by a specific publisher or trading company.

It wouldn’t be wrong to consider these books as a precursor to modern-day trade diaries, including advertisements, often used as New Year corporate gifts in the 19th and 20th centuries.

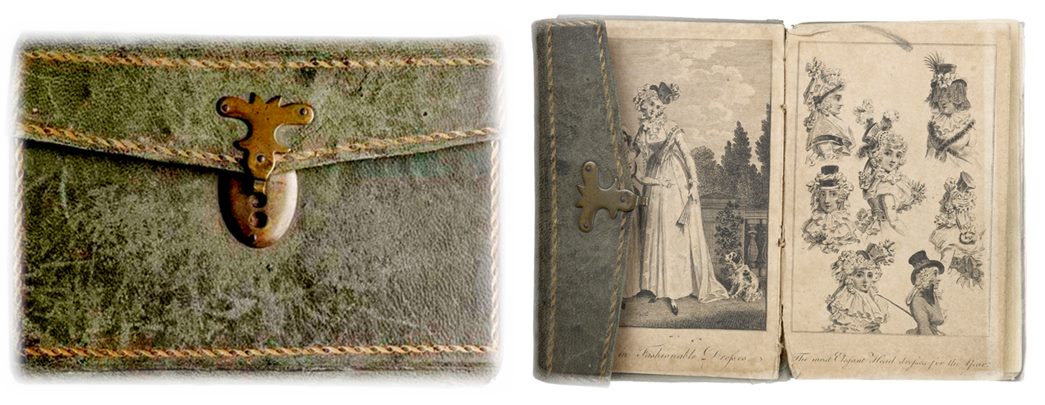

Take the example of the bookseller and founder of Minerva Press (1790), William Lane, who published pocket books aimed at the women who were regular readers of the light romantic fiction and Gothic novels he published. Such pocket books, one of which is part of the museum’s collection , would contain a short romantic story, poetry and tables for recording household expenditure. Inside the cover are prints of ‘Ladies in Fashionable Dresses’ and the ‘most Elegant Head dresses for the Year’. The pocket book was designed to be both light reading and a lifestyle guide for socially aspirant women.

No wonder, these books were even given to girls when they ‘came of age’, probably to equip them with all the ‘necessary’ information.

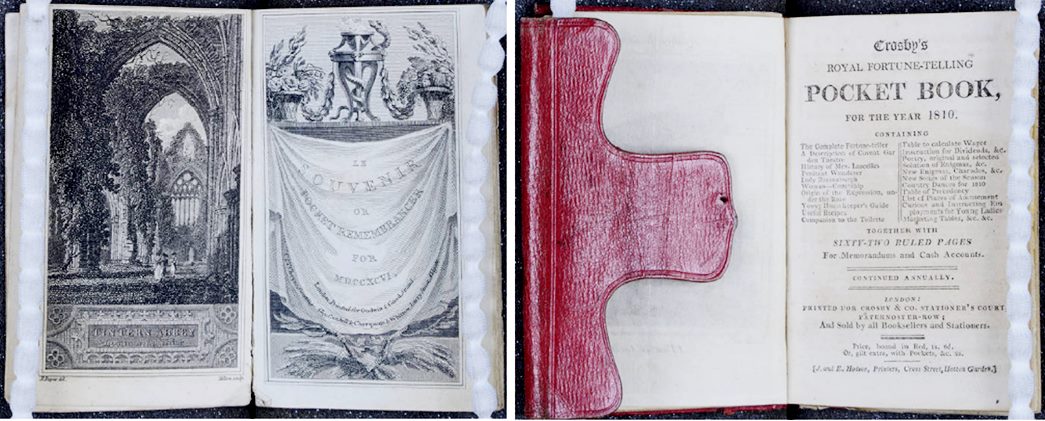

Other volumes in our collection also give us a deeper insight into a Londoner’s life. A 1796 copy of Le Souvenir: or Pocket Remembrancer was used by a Mrs Bingley to record her social outings (including lots of teas at a Mrs Robinson’s!), list letters received, and keep on top of accounts, such as expenses for black lace, mending shoes or a donation to a “poor man".

Mrs Mary Holmes from Soho — owner of an 1810 copy of Crosby's Royal Fortune-telling Pocket Book — used the calendar section to record her outings, which included weekly visits to a library and several trips to the British Museum. She also had days when she “stayed in” or “washed”. Thanks to her jottings, we know her expenses included bonnet cleaning, ribbons, pastries and gin. She added her income too — sums gained from card games or received from her father.

In the blank pages of her 1824 copy of Annually: la Belle Assemblée, or Ladies’ Fashionable Companion, Sarah Palmer from Bermondsey recorded births in her family between 1812 and 1827. While the relationship of the newborns to her is unclear, this volume exemplifies the longevity of pocket books, with Sarah going back to add births (and one passing) for another seven years after its publication.

Not ‘just’ a book!

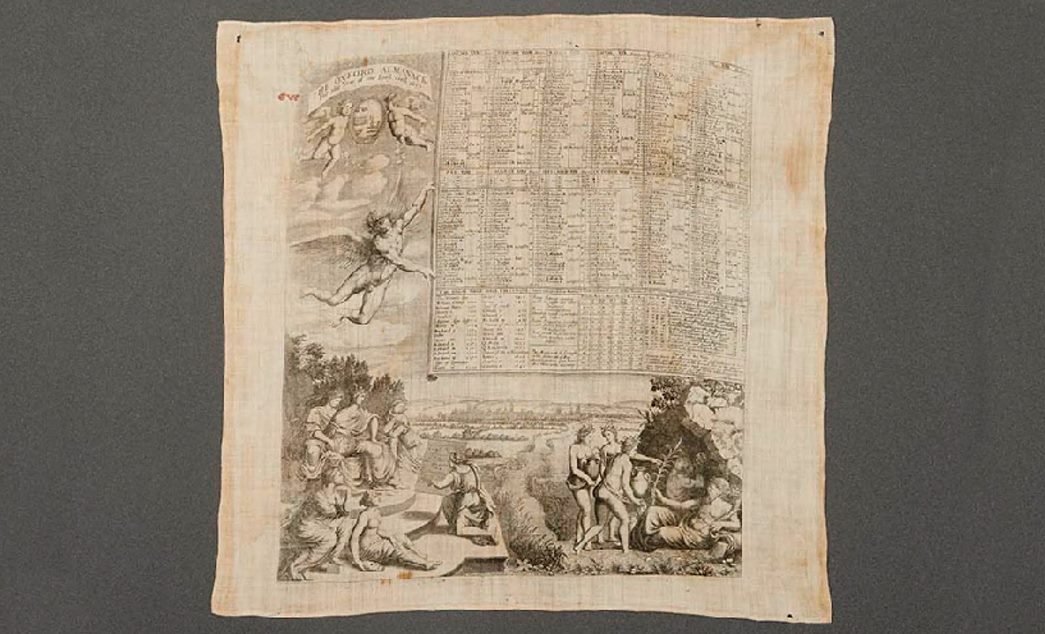

Over time, almanacs were published in various formats, not just pocket books. From being printed on a circular sheet of paper cut and folded to form the shape of a pink rose ('The Rose Alamanck: A Souvenir for 1860') to the Oxford Almanack, which has been published annually since 1674 — on a handkerchief! In fact, one such object is said to be one of the earliest known handkerchiefs to have survived.

While they may not be the second most-sold book in England any more, pocket book/almanacs did for close to 400 years, what smartphones do in the 21st century — provide its owners with a wealth of information in the palm of their hands. And that’s quite a legacy to leave behind, don’t you think?

With thanks to Hazel Forsyth (Senior Curator, Post Medieval) and Lucie Whitmore (Curator, Fashion).