Long before Joseph Bazalgette delivered London City from the Great Stink, Londoners had to live through the stench of dung hills, cesspits and, eventually, the disposal of the contents of fancy-to-everyday chamber pots. So serious was the issue that matters were sometimes even taken to court! Through the museum’s collection, we explore the smelly aspects of early-modern London’s sewage issues.

On 20 October 1660, the diarist and naval administrator, Samuel Pepys, had a nasty surprise when he opened his cellar door and stepped into a “great heap of turds” which had overflowed from his neighbour’s privy. Pepys’ problem was not uncommon and London records show that sewage issues of one kind or another were the greatest cause of litigation and neighbourly disputes. Chamber pots were emptied into the streets or along guttering; cesspits and privies were placed too close to party-walls seeping through the brickwork and rotting timbers; pipes, ditches and streams were blocked with dung and filth.

Alice Wade was reprimanded in 1314 for casting “the filth of her privy into the common gutter” so that it became a “vile nuisance” to all of the neighbours beneath whose houses it passed.

In 1328, for instance, a certain William Sprot complained that the cesspit of his neighbours Adam and William Merre was too near his tenement and was so full of sewage that it had penetrated his stone wall and entered his house “and collects there, causing a great stench”, according to legal records. Most of the cases brought to the attention of the authorities were the result of overcrowding, building alterations and neglect, but occasionally people were indicted for deliberate acts of nuisance. One such was Alice Wade, who was reprimanded in 1314, for casting “the filth of her privy into the common gutter” so that it became a “vile nuisance” to all of the neighbours beneath whose houses it passed. In 1400, embroider Robert Asshecombe took action against his neighbours Gilbert and Mazera Accon, who had broken-down walls and openings to the latrines in their tenement in Woodstreet, exposing their “private business” and wafting “evil odours”. They had also made things worse by flinging their “filth and rubbish into his close”. Another case in 1613, resulted in the arrest of Jane and Charles Browne of Whitechapel “for emptying a great quantity of night-work into the common sewer to the general annoyance of all the inhabitants”. The couple were committed to the stocks in Artillery Lane for six hours.

Example of a late 13th-century garderobe at Chirk Castle in Wales. (Courtesy: Wikimedia Commons)

A private public affair

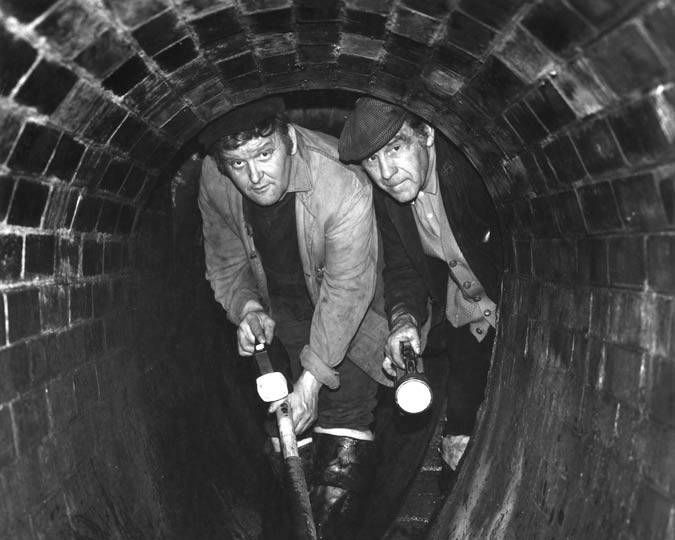

Part of the problem for Londoners was the lack of private sanitary facilities. In 1579, for instance, the 85 residents of All Hallows by the Tower had just three privies between them. Many citizens were forced to use the public latrines which were dotted around the City of London, and though the wealthiest households had their own garderobes (toilets) or closets, they often shared a contiguous latrine and communal cesspit. As per City custom, men “cleansed their jakes according to their falls by even portion” but where there were adjoining latrines and privies, which household was responsible for maintaining the plumbing and the cost of cleansing? Which family would have to endure the dreadful prospect of having the ordure carried through their house? Not surprisingly, responsibility for the upkeep of cesspits and latrines was taken very seriously; people left money for the care and cleansing of privies in their wills and the civic authorities tried to ensure that they were correctly built, maintained, regularly cleansed and emptied at night.

Within the chamber

Chamber pots of silver are occasionally listed among the household effects of the well-to-do, but the majority — made in pewter or ceramic — seldom feature in domestic accounts. Pewter chamber pots are mentioned more often, because landlords and citizens with a little more disposable income, appreciated their durability. But paradoxically, the very quality which attracted victuallers and householders to the material also attracted the attention of thieves. Thefts of pewter chamber pots were not uncommon, and the going-rate for a standard-sized vessel in the early 17th century, was 6 pence; though the pot that Alice Herstbye stole from Sir Edward Leeche in 1624, was valued at 2 shillings (24 pence).

On the pot

The Museum of London’s collection of 16th and 17th century chamber pots is quite impressive: a majority are made from earthenware with or without a colourful lead-glaze. Some are represented by piles of smashed shards, while others have missing handles, chips and other damage. Several were excavated from cesspits; presumably dropped by mistake or discarded and dumped with other household waste. A few even retain evidence of their contents. Traces of urine, in particular, can be seen, and one of the pewter pots has some golden streaks from urea and bile salts.

By far the largest group were made on the Hampshire/Surrey border, which were available in two basic types: those with a narrow, upright rim, often thickened or bevelled internally for a lid; and those of slightly more globular form, with a wide, rim flange. The former glazed internally, and the latter, glazed inside and out. Both types have a single loop handle. The sizes of the pots vary quite considerably and at least one example is potty-sized for a young child.

The collection also includes several late 17th century examples in tin-glazed earthenware (delftware) from the Montague Close or Pickleherring pot-houses in Southwark; the latter holding a stock of 3,000 chamber pots in various stages of production in a probate inventory of 1699. But, perhaps, the most impressive group were made in the potteries of Harlow, Essex (known erroneously as Metropolitan ware). These are decorated with slip (coloured liquid clay) and often bear inscriptions such as ‘Fast and pray pitty the poor’; ‘Be Merry and Wise’; ‘Feare God Honor the King’ and, rather more relevant to the purpose: ‘BREAK ME NOT I PRAY IN YOUR HAST FOR I TO NON WILL GIVE DESTAST, 1663!

Header image: A doctor meeting a patient, a woman pours a chamber-pot into the street. Etching by T. Rowlandson, 1789. Wellcome Collection. Public Domain Mark

Stinky Museum Card Game

We've got a lot of stinky things at the Museum of London, from Roman toilets to Medieval wee pots. Play our stinky card game to find out more and see who comes out... bottom?!

![A chalk-lined early Medieval cesspit at Brooks Wharf, Upper Thames Street, London. (ID no.: BHD90[22])](/application/files/2516/3619/8519/1_chamber_pots_1045_early_medieval_cesspits_london_MoL.jpg)

![Chamber pot found in Weston Street, Southwark. (ID no.: BVM12[868]<temp7>; this item is on display at the London Bridge)](/application/files/9116/3698/8552/4_chamber_pots_1045_Chamber_pot_found_in_Weston_Street_MoL.jpg)