The Museum of London has acquired an extremely rare silver plate, originally owned by the famous Londoner Samuel Pepys. Curator Hazel Forsyth explores what Pepys's plate tell us about the man and his times.

This silver plate, with knife and fork scratch marks, belonged to Samuel Pepys: Londoner, naval administrator and famous diarist.

The rim is engraved with the coat of arms of the Pepys family, and the underside has London hallmarks (symbols stamped into the silver, testifying to its purity). Also on the plate's underside are the date letter for 1681/2 and the maker’s mark ‘MK in a lozenge’ indicating that it was made in the workshop of Mary King in Foster Lane: just five minutes’ walk from the Museum of London. There's a much later scratched inscription, reading: ‘date 1681’. It is possible that the plate was acquired from the goldsmith Richard Hoare, and the engraving executed by Benjamin Rhodes who was one of his sub-contractors.

A rare prize

Very little 17th century silver has survived, because it was regarded as an investment and was constantly refashioned or melted down. This plate is one of just three surviving items of silver known to have belonged to Pepys. The other two are now in the United States of America. It's very exciting for the museum to put Samuel's silverware on public display in the heart of London, so close to where it was made.

The man and his era

Portrait of Pepys, 1666

Collection of the National Portrait Gallery.

Samuel Pepys, the son of a tailor, was born in Salisbury Court just off Fleet Street, on 23 February 1633. Following graduation from Magdalene College, Cambridge, Pepys worked for his influential cousin, Edward Mountagu, 1st Earl of Sandwich, whose patronage helped to secure his appointment in 1660 as Clerk of the Acts to the Navy Board. The Navy Board responsible for the building and repair of ships and the management of the dockyards.

In the same year, Charles II was restored to the throne, and on New Year’s Day, Pepys started to write a diary, a personal ‘Journall’ and chronicle of London social life and current affairs, which he continued for nine years until fear of blindness caused him to abandon it.

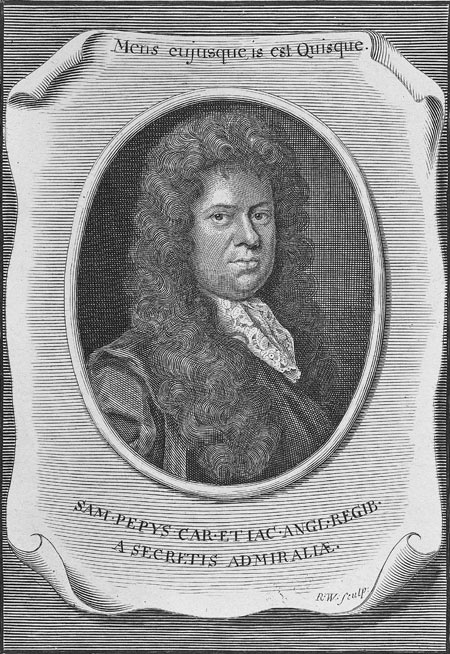

Print showing Samuel Pepys, 1793

From an original by Sir Godfrey Kneller

During the course of the diary period, Pepys achieved considerable professional success and was soon rich enough to live in style and indulge his interests and collecting passions for books, prints, silver, household-furnishings, ship-models and ‘curiositys’.

In 1688 Pepys resigned his position as Secretary to the Admiralty, a position he had held for 15 years. He retired in comfortable seclusion to the home of his friend William Hewer at Clapham. After a long illness, Pepys died in his seventieth year on 26 May, 1703. On the same day, his friend and fellow diarist John Evelyn described him as:

‘a very worthy, Industrious, & curious person, none in England exceeding him in the Knowledge of the Navy, ...universally beloved, Hospitable, Generous, Learned in many things, skill’d in Musick, a very greate Cherisher of Learned men...’

Silver and gold

When Pepys assessed his personal wealth at the beginning of his Diary, he had an estate worth just £25 and was much ‘troubled with thoughts how to get money’ to pay off his debts, though he acknowledged ‘My own private condition very handsome; and esteemed rich, but endeed very poor, besides my goods of my house and my office, which at present is somewhat uncertain.’

Since every penny counted he made a point of keeping just three pence in his pocket while out drinking with friends, lest he be tempted to spend more. Before long his financial worries were eased with his appointment to the Navy Board and a salary of £350, but by then Pepys had begun to spend more than he earned and he was concerned ‘to look about me to get something more than just my salary, or else I may resolve to die a beggar.’

Pepys’ finances improved further with a shower of bribes and gratuities for commissions, contracts and services rendered in his work for the Navy, and within a couple of years Pepys was worth £1,000. At the end of the Diary period, Pepys was rich, with a salary in excess of £500 a ‘mighty handsome’ home, a painted and gilded coach, and £10,000 in savings.

At a time when wealth was demonstrated not by the size of the house but in its furnishings and silverware, Pepys gradually began to acquire plate, made of silver, for domestic use. Some of it was by direct purchase, but more often it came in the very welcome form of a gift or perquisite of office. In July 1664, for instance, he received a fine leather case with a pair of silver-gilt flagons, the gift of Mr Gaudens, ‘which are endeed … so noble that I hardly can think they are yet mine.’ These were soon displayed to the envy of Pepys’ dinner guests, with a dozen silver salt cellars besides the ‘great Cupboard of plate’. Further acquisitions followed.

By February 1666, Pepys had so much silver that he was able to pick out pieces ‘to change for more useful plate’. In December he placed an order with the Goldsmith Sir Robert Vyner for twelve plates from Captain Cocke’s gift of £100, increasing his stock of plates to thirty overall. As he noted at the end of the year, ‘One thing I reckon remarkable in my own condition is that I am come to abound in good plate, so as at all entertainments to be served wholly with silver plates, having two dozen and a half.’

One of the great advantages of so much silver was the opportunity to show off and on 8 April 1667 Pepys wrote:

I home and there find all things in good readiness for a good dinner … we had, with my wife and I, twelve at table; and a very good and pleasant company, and a most neat and excellent, but dear dinner; but Lord, to see with what envy they looked upon all my fine plate was pleasant, for I made the best show I could, to let them understand me and my condition, to take down the pride of Mrs. Clerke, who thinks herself very great.

We hope that Pepys would appreciate seeing his silver on display, still arousing pride and envy among Londoners three hundred years later.