London has extremely polluted air. Toxic emissions on Oxford Street breached safe legal limits in the first month of 2017, and have only got worse since then. Two of our curators look back at the history of the city's air, to see how London solved pollution problems in the past.

Even before factories and cars began to pump pollutants into the city's atmosphere, Londoners have been no strangers to noxious air. 17th century writers complained of the foul smoke emitted by burning sea coal, and backed-up chimneys suffocated people in their beds every year for centuries. But there were two times in London's history when the air became not just foul-smelling but actually deadly: the Great Stink and the Great Smog.

By the 1850s, London was the world’s most powerful and wealthiest city. But it was also the world’s most crowded city with growing problems of pollution and poverty that threatened to overwhelm its magnificence. At the beginning of the 19th century less than 1 million lived in London, but by the 1850s the capital’s population had doubled and, by the end of the 19th century 6.5 million lived in an ever expanding Greater London. London was now home to one in five of the UK population.

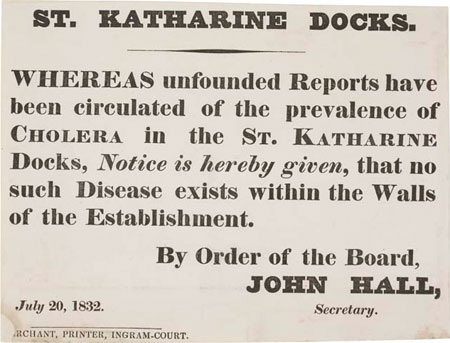

Printed cholera notice issued by the St Katharine Dock Company, 1832

Denying rumours of a cholera outbreak within the London docks.

Such rapid population growth placed a tremendous strain on London’s public services, in particular its fresh water supply, waste disposal and sewage systems and also caused a severe housing crisis. The greatest challenge for the city authorities thus became how to keep its growing and densely packed population healthy and nourished and free from disease.

The threat of mass epidemics of diseases such as cholera and typhoid in such an overcrowded city were never far from the surface. Whilst those living in overcrowded slum conditions were at greatest risk of infectious disease it was not just the poor who died young.

Tuberculosis, smallpox, cholera and typhoid were no respecter of class and killed both rich and poor. In the mid-19th century the high death rate amongst young children brought average life expectancy in London down to just 37 years.

Dirt and smell were facts of urban life that equally contributed to the poor health of Londoners. People could not cross a road without the benefit of a crossing sweeper who cleared dust and horse manure from their path. The ‘summer diarrhoea' that occurred annually and killed many, particularly infants was largely caused by swarms of flies feeding on manure, rotting food and human waste left exposed in the hot, steaming streets.

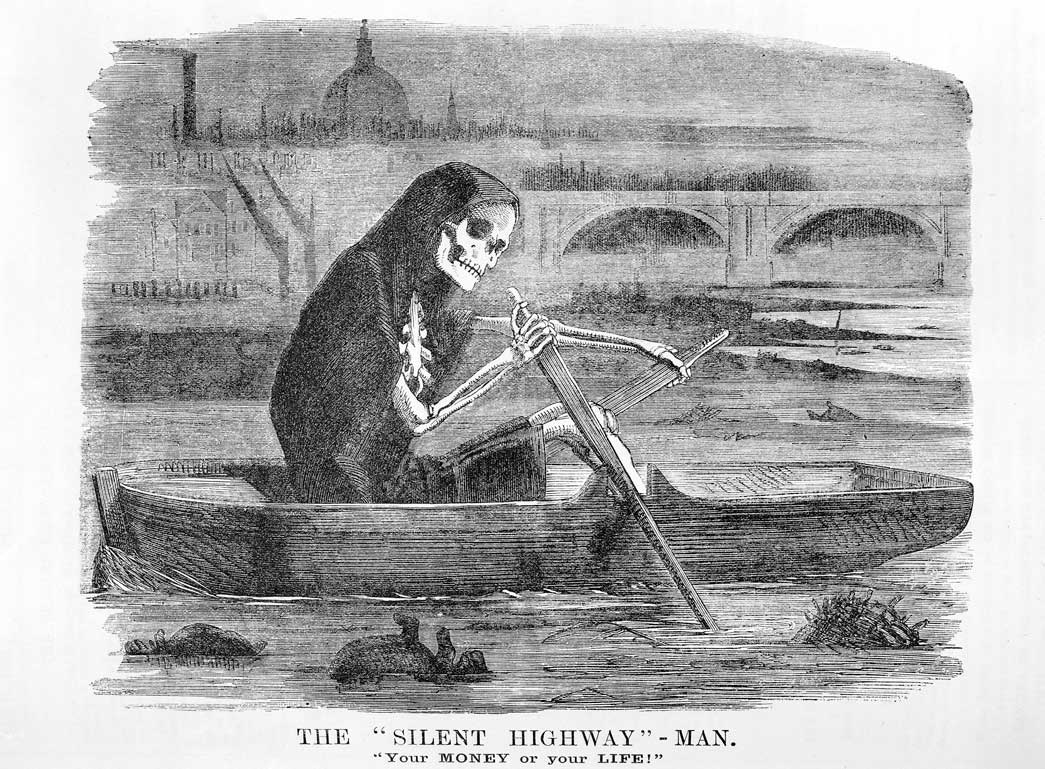

Smell was a potent characteristic of London life. In the 1850s London experienced the Great Stink, when the River Thames became a giant sewer overflowing not only with human waste but also dead animals, rotting food and toxic raw materials from the riverside factories.

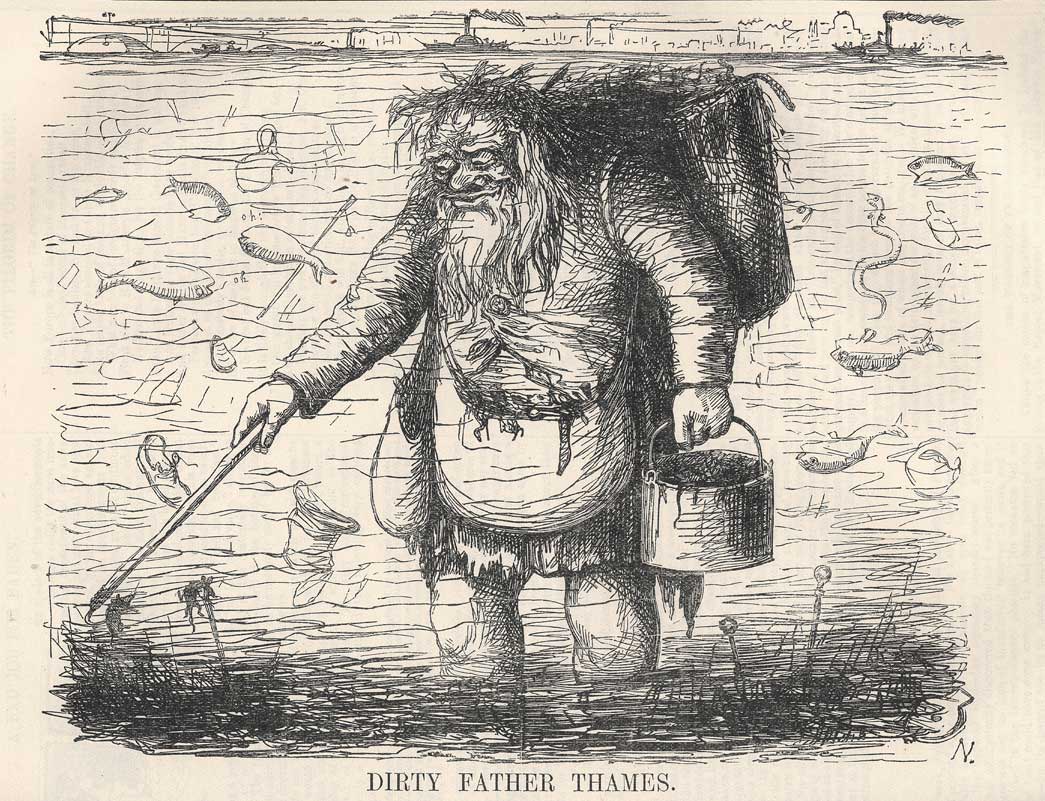

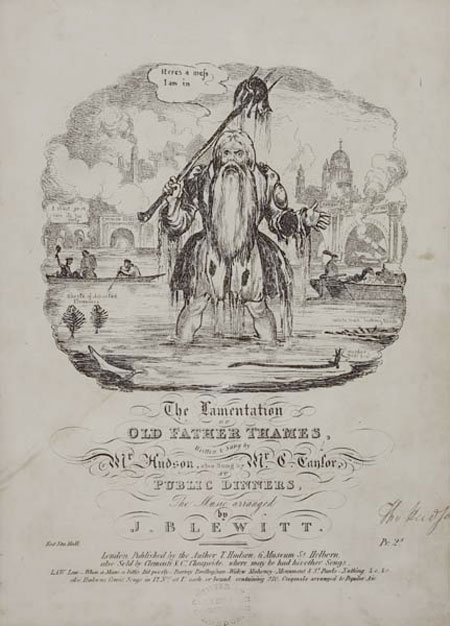

The lamentation of Old Father Thames, 1850s

Songsheet for a popular ballad mocking the filthiness of the river.

The Thames, once the lifeblood of the city, now became a river of death. Londoners, overwhelmed by the smell, retreated behind closed doors and heavy curtains soaked in lime.

In the 1850s, there was no understanding that diseases, particularly cholera, were caused by germs in polluted water. Instead, the miasma theory of disease was dominant, which taught that contagion spread on the air, with the foul smells directly causing illness. This gave the Great Stink added terrors, as Victorian Londoners believed simply smelling the noxious odour of the Thames could kill them.

The summer of 1858 was one of the hottest in memory, and the heat and lack of rain left the city stinking and the Thames a river of effluent. The Houses of Parliament had to be closed, as the river running beneath its windows became too noxious. Even soaking the window-blinds in strong-smelling carbolic of lime failed to keep out the Great Stink.

Such appalling conditions in the world’s greatest city forced the authorities to act.

Clare Market, 1890

This market, surrounded by slums, sold fish, meat and vegetables.

The risk of water-borne disease was reduced by the building of Bazalgette’s great sewage system and Dr John Snow’s discovery that cholera was carried in contaminated water rather than through smell. A co-ordinated approach to the disposal of waste led to a reduction in the swarms of disease-spreading flies. In 1850-1860 the area of Whitechapel, in east London, had a typhoid death rate of 116 per 100,000. By 1890-1900 this had been reduced to just 13 per 100,000.

But whilst many benefited from such improvements, poverty continued to be a cause of poor health for many. Up to one third of late Victorian Londoners were identified as living in some degree of poverty. There was a growing polarisation between the health of the ‘better off’ who were moving to modern well-ventilated homes with plumbing in the healthier suburbs and those in the inner city who continued to live in cramped, unsanitary slum conditions.

For these Londoners smell was not so easily removed from their lives. As George Gissing noted in 1893 when describing Southwark, "an evil smell hung about the butchers' and the fish shops. A public-house poisoned a whole street with alcoholic fumes; from sewer-grates rose a miasma that caught the breath."

A starving family, 1900

A poverty stricken East End family. A mother with her three children, all dressed in rags.

Those born in London were distinguished from new arrivals to the capital by their unhealthy pallor, weak stature, a habit of talking louder than ‘outsiders,’ with a distinctive slang and accent affected by their need to breath heavily through their mouths due to their congested nasal passages. The skin, clothes and nostrils of Londoners were filled with a compound of powdered granite, soot and still more nauseous substances. The biggest cause of death in London remained consumption or tuberculosis and lung disease. Recruitment for the Anglo-Boer War at the end of the 19th century had also revealed the poor health of Londoners when only 2 in 9 working class males were found to have been fully fit for combat. In 1903 the American Jack London equally noted the incapability of native Londoners to undertake demanding manual work.

"The air he breathes, and from which he never escapes, is sufficient to weaken him mentally and physically, so that he becomes unable to compete with the fresh virile life from the country hastening on to London Town to destroy and be destroyed. It is incontrovertible that the children grow up into rotten adults, without virility or stamina, a weak-kneed, narrow-chested, listless breed, that crumples up and goes down in the brute struggle for life with the invading hordes from the country. The railway men, carriers, omnibus drivers, corn and timber porters, and all those who require physical stamina are largely drawn from the country."

Jack London, The People of the Abyss, 1903

The Victorian cult of cleanliness served to separate and divide the classes even further. As bathrooms and running water became more available in the homes of the wealthy the poor were more obviously identifiable on the streets as ‘the great unwashed’. Smell created a potent barrier between the social classes as the poor suffered from a lack of washing facilities and the high cost of soap and disinfectant. Middle class charity workers not used to such conditions often found the smell of the slums unbearable and heaved as they carried out their ‘good works’. Christian charities linked cleanliness to the prevailing concept of the 'civilising mission' of Empire believing it to stand for progress. The distribution of free soap and disinfectant was believed to create not only healthy bodies but also healthy minds.

Section of Charles Booth's Descriptive map of London Poverty, 1889

Shown is Victoria Park and the poor housing to its east.

Religious and charitable organisations worked tirelessly not only to improve the conditions of the poor but also to place pressure on the government and local authorities to take greater responsibility for the health and welfare of London’s poorest citizens. Working closely together they initiated and funded projects that gradually improved the life of all those living in London’s poorest areas.

The creation of landscaped green spaces such as Victoria Park in Hackney provided a ‘vital lung’ for those living in the slums. By 1880 the Metropolitan Drinking Fountain and Cattle Trough Association had erected 800 drinking fountains and troughs providing fresh water to up to 300,000 Londoners and 1,800 horses daily during the summer. Today, the network of parks across the city are still known as the "Lungs of London".

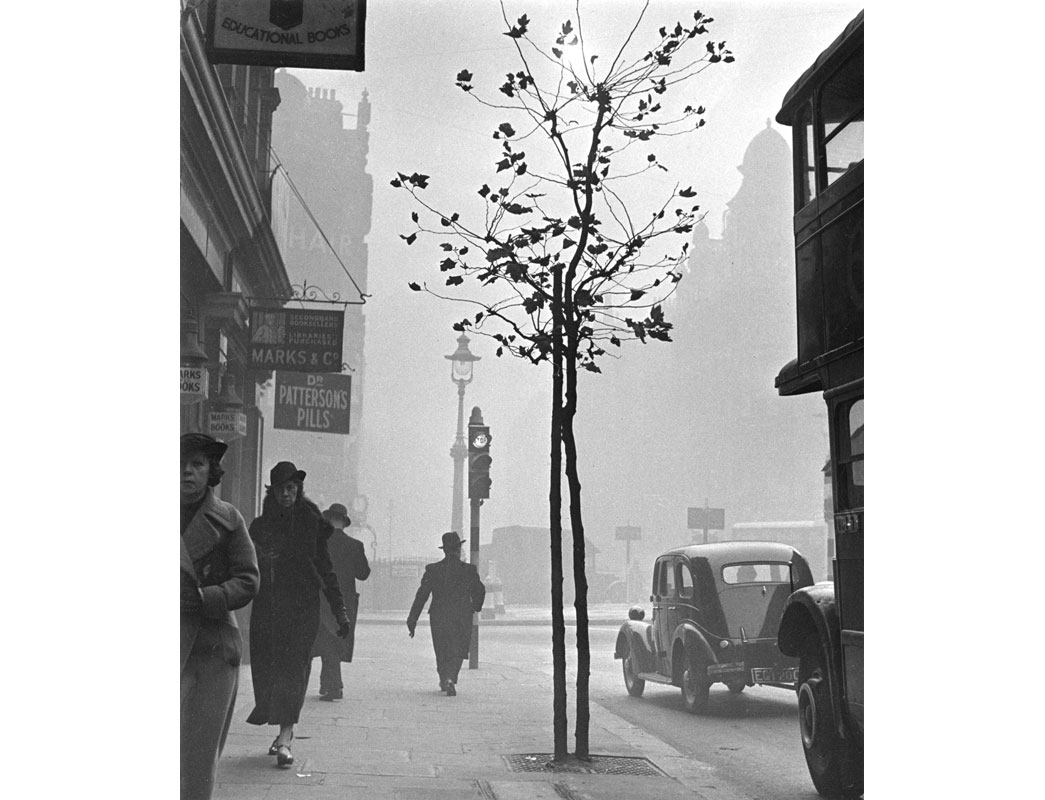

But all the reforms of Victorian moralists could not remove the fumes of London's industry, homes and, as the 20th century went on, motor vehicles. The infamous London fogs, known as "pea-soupers", choked the city on a regular basis.

The last time that Londoners faced a visible killer smog was in December 1952. Its impact was profound and led, after lengthy deliberation, to the creation of the Clean Air Act of 1956. It was a particularly scary moment for those living in the city. The smog penetrated into people’s homes, creeping through cracks and under doors. If one ventured outside, visibility was virtually non-existent. Those suffering from existing lung ailments were particularly liable to succumb to the poisonous smoke.

'We Want Clean Air' protest banner at Paddington, 1956

© Henry Grant Collection/Museum of London

At first, government refused to make the connection between the smog and the premature death of thousands of Londoners. An outbreak of influenza was considered as an alternative or contributing factor for the increased level of mortalities in the metropolis. Others blamed unseasonable weather conditions or felt that it was just one of the consequences of living in a large conurbation where coal was burnt to make gas and electricity, power machinery and above all to heat homes.

We are more and more aware today of extreme weather conditions, such as strong winds or torrential downpours. It is interesting that the Great Smog of 1952 was also the result of a set of unusual atmospheric conditions as an anticyclone trapped the smoke of the city matched by an easterly wind that carried further polluted air from the continent. The weather had been bitterly cold in November and December but for Londoners this was something quite normal for the winter months. They retreated to their homes and burnt coal to keep warm. Everything would have been tolerable had not been for the abnormal weather conditions that led to the smog hanging over the city. One of the most unpleasant gases caused by the burning of coal was sulphur dioxide but in the moist air it was converted into a much more dangerous and deadly liquid - sulphuric acid!

The Clean Air Act did much to stop the worst of the London smog, but modern pollutants, although less visible, are scarcely less deadly than cholera or coal fumes. By some estimates, 9000 people die prematurely every year because of London's poor air quality. The Mayor of London plans to establish an Ultra Low Emissions Zone surrounding the centre of London by 2020, which might cut down the worst pollutants. But for now, as in centuries past, breathing in London remains a risky business.

How are we tackling London's current pollution crisis? Read our article from the City of London's Air Quality Manager, Ruth Calderwood.