The Museum of London holds a Library collection of around 40,000 volumes. To celebrate Word Book Day, Lluis, the museum’s Librarian, shares some of his favourite volumes and the stories these have to tell.

Bookshelves of the rich and famous

Through the history of the Museum of London (and our two parent institutions) we have added to our Library books with illustrious former owners. We have volumes owned by King William IV and Queen Victoria; an opera music score book gifted to Lady Hamilton, the lover of Lord Nelson; a self-published book by architect and collector Sir John Soane; even an embroidered bible associated with Queen Elizabeth I.

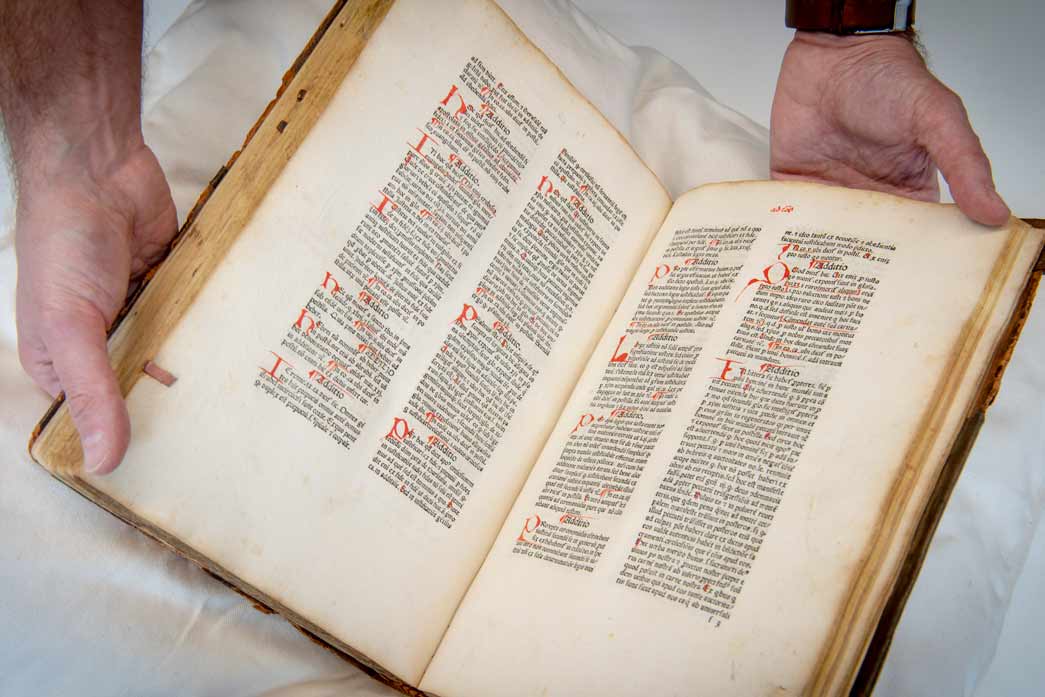

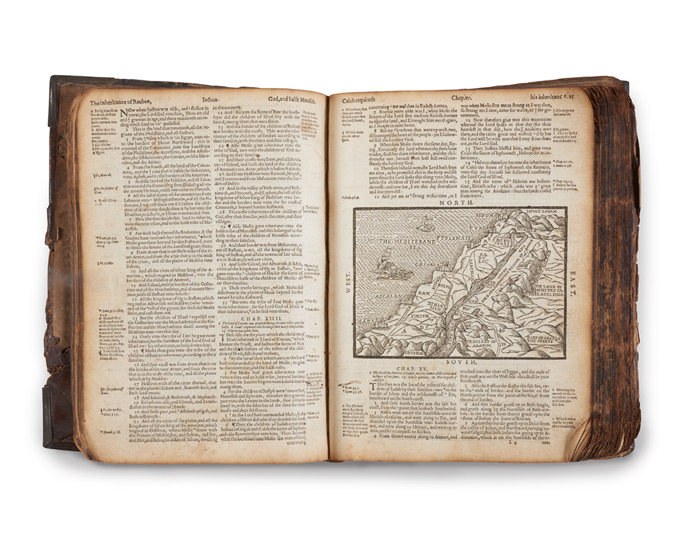

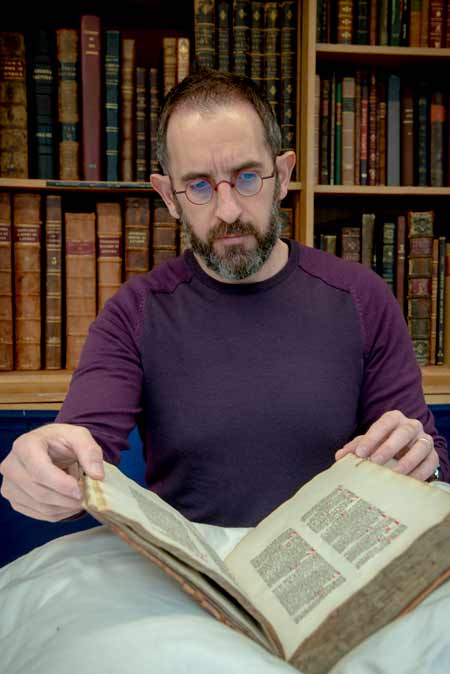

My favourite famous volume goes further back in time. The oldest book in our collection is a medieval incunabulum, a 1478 edition of the Postilla in epistolas Pauli, also called Epistles or Letters of Paul. As we see from one of the bookplates, this particular volume belonged to William Morris, the Victorian artist, designer and poet. It was part of his private library in Kelmscott House, Hammersmith.

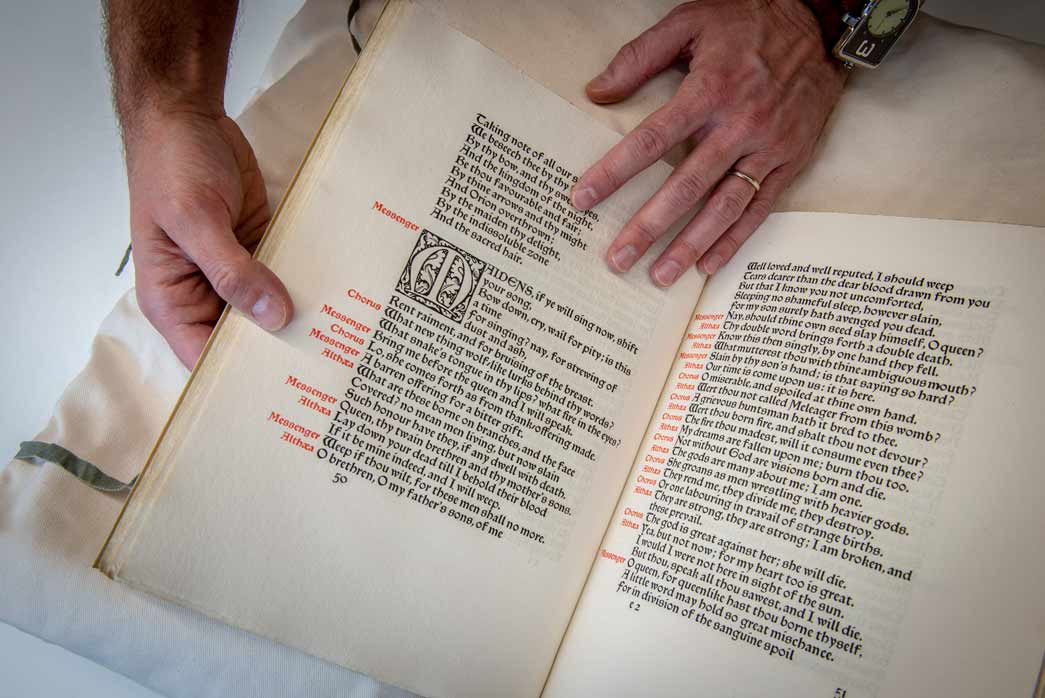

The book, printed in black ink, gothic type and double columns, also has some handwritten additions, added in the text in very bright red ink. When placed next to A. C. Swinburne’s Atlanta in Calydon: a tragedy, also in our library, and published by Morris’ Kelmscott Press, one cannot help but notice the exquisite medieval feel that trickles from one volume onto the other.

The format of the text, the red against the black, the crafted binding… this is a textbook example of Morris taking inspiration from early printed books for his own published volumes, a step towards his revival of the crafts and aesthetics of the medieval past.

Handwritten history: diaries and manuscripts

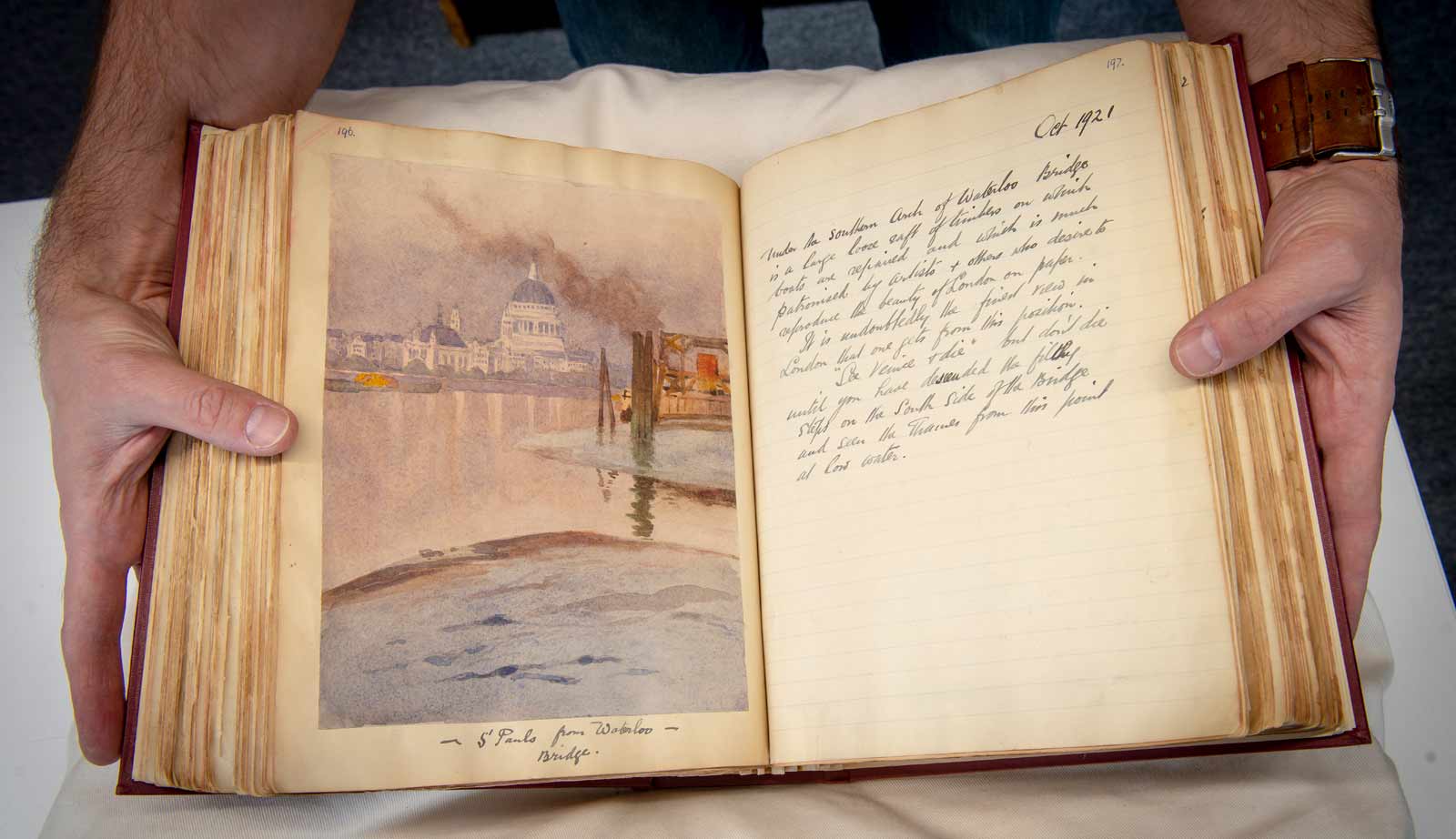

Hand-painted details from Macey's diary

The library collection holds over 200 hand-written manuscript volumes, ranging from family account books to individuals recording their visits to London. We also have several memories (with reminiscences of life in the capital) and personal diaries.

My favourite diary is that of Frank Halden Macey (born in London in 1855), kept originally in 24 volumes between 1876 and 1942. In its pages we learn that Mr Macey was interested in theatre, was also a keen cyclist and enjoyed painting quick watercolours when travelling around London. His diaries have dozens of examples of these, beautiful snapshots of life in the capital, from views of the river Thames and Hampstead village to many of the London parks and forests.

The diaries are also a window to Macey’s personal experiences in historical events: on the entry for 10 August 1940 he says: “…the future is still uncertain. The only things that is certain is that Britain will finish off Adolf Hitler one day.”

On the last entry of the diary dated 10 November 1942, he tells of his visit to London from St. Albans, where he moved in 1941. Macey finds London “like a city of the dead”, Liberty’s department store “stagnant as they could get nothing to sell”. This entry, a loose letter, was never bound in the existing volumes; Mr Macey died the following 10 March 1943 in St. Albans, aged 87.

Fragments of the past

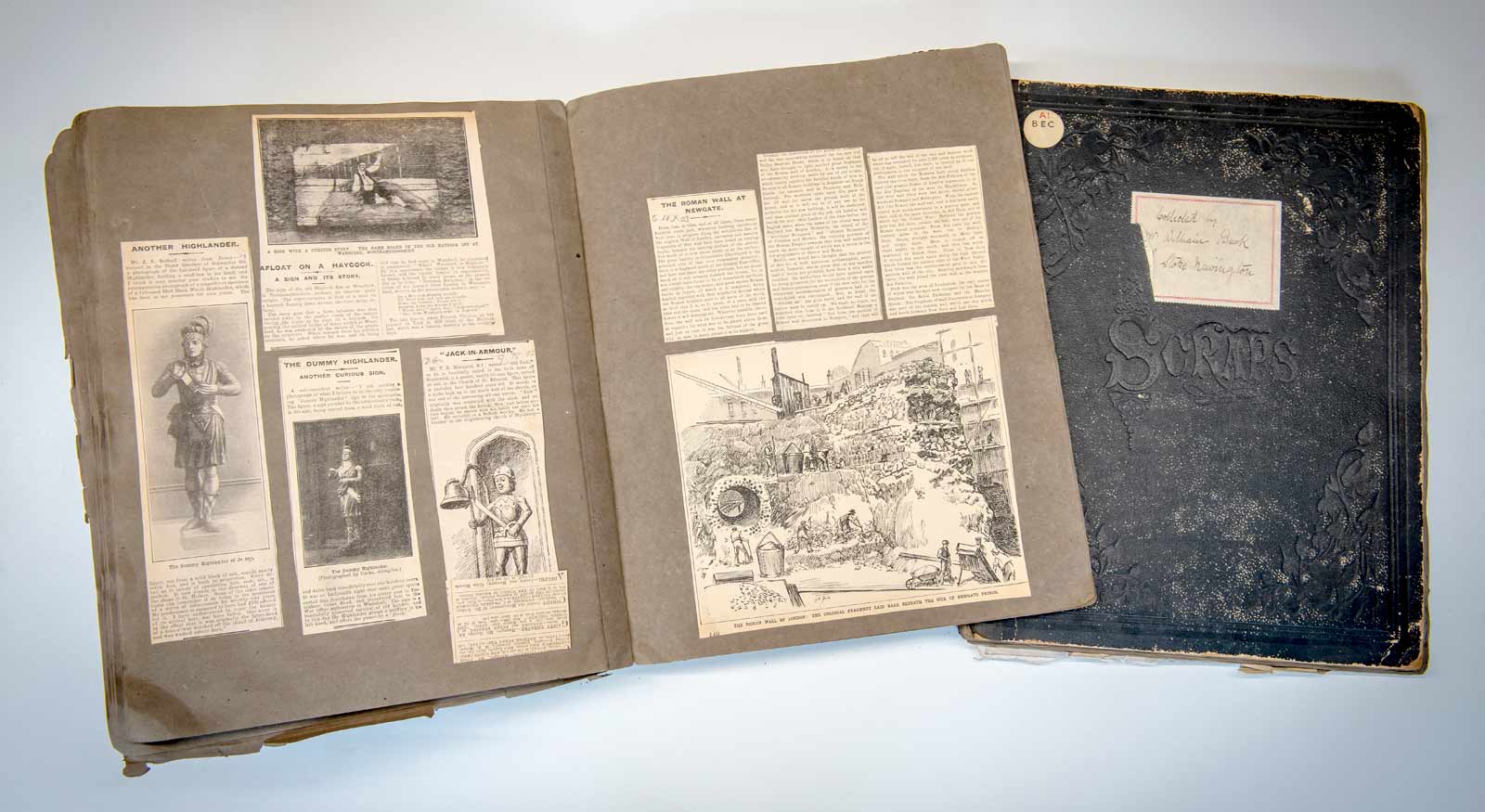

Along with manuscripts and diaries, scrapbooks are among the most unique items libraries can hold. Scrapbooks start normally as blank volumes in which various items such as newspaper clippings or pictures are kept, glued. Often they reflect someone’s lifetime passion and dedication to a subject: some examples in our collection cover London’s pleasure gardens, lottery bills, the relics of King Charles I; many are simply collections of arbitrary images of London.

Among our scrapbooks there is a set of two that I find particularly interesting. The volumes were compiled by Mr. William Beck, a Quaker architect from Stoke Newington. Beck was clearly concerned with the effects the growth of the city was having on its historical buildings. Between 1895 and 1905 he collected newspaper articles dedicated to ‘vanishing London’: reports, photographs and letters to the editor denouncing building of historical interest being demolished.

Among the hundreds of press cuttings we read about numerous disappearing taverns and coffee houses, churches, building associated with Dickens, even complete neighbourhoods in the Strand and Knightsbridge areas. However, this turn of the century’s transformation of London sometimes facilitated the discovery of earlier archaeological structures. For example, an article dated 13 September 1901 mentions the finding of 18th century wooden water pipes near Regent St. Another from 10 October 1903 covers the discovery of a big part of the Roman wall under the Newgate prison, brought to light (even of temporarily) before the construction of the new Old Bailey.

My favourite oddity

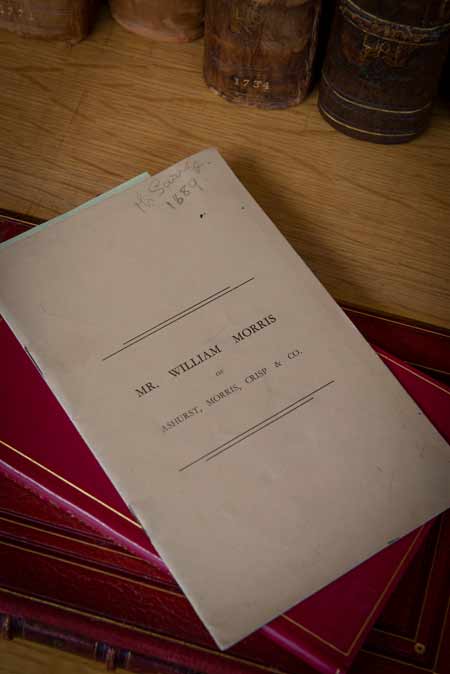

Pamphlet from William Morris

The pamphlet lists solicitor William Morris’s life achievements.

Sometimes in libraries, like in life, we stumble with little curiosities when we least expect to. My favourite accidental find is a little pamphlet by a William Morris. Not the famous William Morris mentioned above, but a solicitor and businessman born in 1855. In 1932, two years before his death, Morris was asked to list the highlights of his career by a private club to which he belonged.

We soon discover that Morris was a very interesting character of the time: for instance, he promoted and helped passing over 100 Acts of Parliament; he was involved in constructing railway lines in Mexico and was Chairman of the Rowton Houses Ltd., a chain of affordable hostels for working class. Londoners however should be aware that he was also responsible for what has become one of London’s most loathed transport hubs: Bank Station.

According to the pamphlet, Morris “conceived the idea of making an underground station […] with public subways and access from the streets”. His original design, which also included underground connections with other nearby railway services, was “a success” and was implemented by railway companies in other London locations “notably Piccadilly Circus” he records, proudly.

Find out more about the Museum of London Library.