Composer, Suffragette, Activist. With a sheepdog at her side, and a bottle of fine red wine close at hand, Dame Ethel Smyth can seriously be considered to be a top contender for “most interesting dinner party guest” among the figures represented in the Museum of London’s galleries.

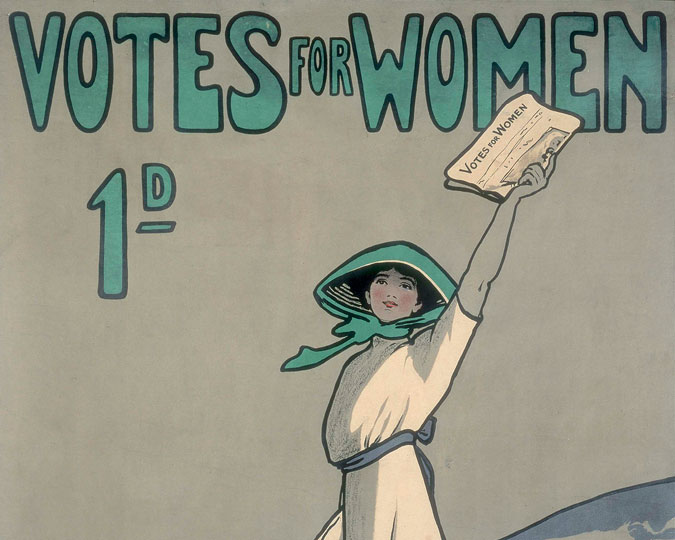

Dame Ethel Smyth’s prodigious career in music composition earned her an international reputation. In 1903, she broke ground as the first female composer to ever have her music performed at The Metropolitan Opera in New York City. In London, however, she earned a second legacy as a member of the Women’s Social and Political Union (WSPU), investing her talents and passion in the “Votes for Women” campaign.

Ethel Smyth was a well-known composer who joined the Women's Social and Political Union in 1910, after hearing Emmeline Pankhurst address a meeting at the home of Lady Brassey. (ID no.: 50.82/1437)

Born in 1858 in Sidcup, Smyth was raised at a time when composing was regarded as an unseemly area of practice for a woman; and this prejudice dogged Smyth in her professional life. In spite of her critics, famous Russian composer Pyotr Ilyich Tchaikovsky would state that “Miss Smyth … can seriously [be considered] to be achieving something valuable in the field of musical creation,” in 1888. (Her 1906 “long-neglected maelstrom of an opera”, ‘The Wreckers’, was performed after many decades at Glyndebourne in 2022.) During a time of great scepticism towards women in the music industry, Smyth was poising herself to cause a fuss.

And so, we might think in hindsight that it was no surprise Dame Ethel Smyth would, in time, commit herself to the Votes for Women campaign. After befriending Emmeline Pankhurst, which Smyth describes as “the fiery inception of what was to become the deepest and closest of friendships”, she formally joined the WSPU in 1910. Yet again, Smyth would deploy her flair as a composer to great effect on the London scene.

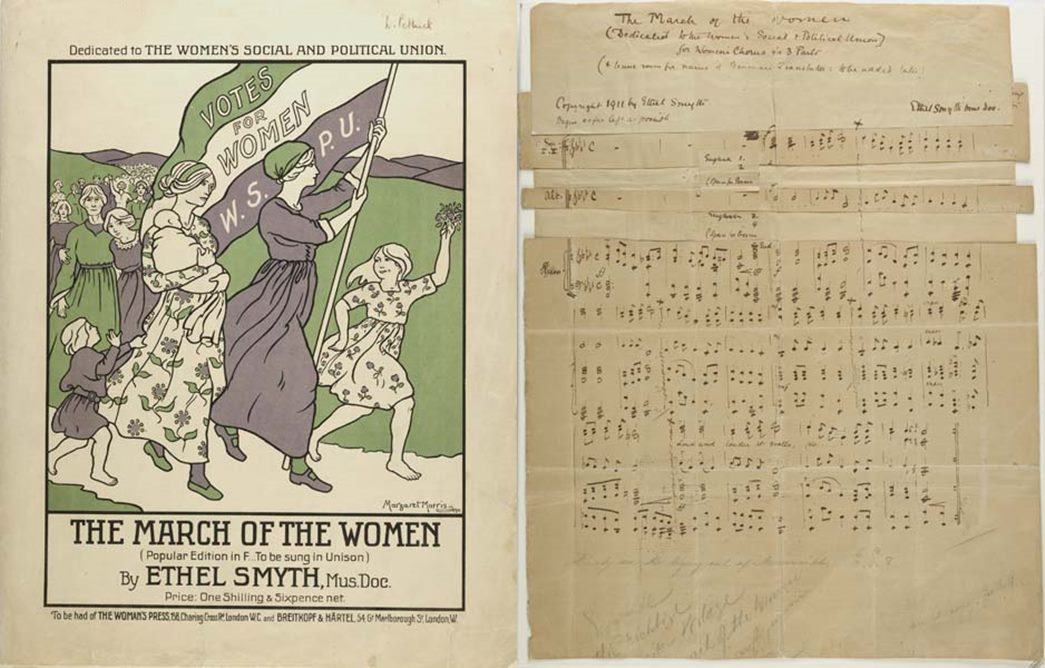

‘The March of the Women’

Music score composed by Ethel Smyth with words by Cicely Hamilton. ‘March of the Women’ was played for the first time in public on 21 January 1911 at a social event at Suffolk Street Galleries to welcome those imprisoned after Black Friday. (ID nos.: 50.82/768a; Z6234a)

The March of the Women (1911), composed and handwritten by Smyth, is among the collection of items preserved by the museum to document her legacy in the city. First played on 21 January 1911 to welcome the release of Suffragettes imprisoned during a Black Friday protest late in the previous year, it would quickly become the foremost protest song of the movement! Described as a hymn and a call to battle for the Suffragettes, The March of the Women gave women courage and solidarity that empowered them to undertake militant activity in the name of the Votes for Women campaign.

Knowledge of The March of the Women was not just confined to members of the WSPU. Processions of Suffragettes carried cards printed with the music, and accompanying lyrics by Cecily Hamilton. Members of the public would, in turn, become familiar with the piece after witnessing these marches. For both empowering the WSPU, and raising the organisation’s profile among the public, Smyth was presented with a commemorative baton by the WSPU in 1911 to formally thank her for the impact she had made upon the movement.

But Smyth was not yet done. At 54, with a respectable background and a ground-breaking professional reputation, Smyth was not spared a prison sentence for her involvement with the WSPU. With approximately 150 other women, Smyth participated in the window-smashing campaign of March 1912. Alongside Emmeline Pankhurst, Smyth targeted the Secretary of State for the Colonies, Lewis Harcourt. The pair located his office at the Houses of Parliament, breaking his windows in response to condescending comments that he made about the Votes for Women campaign. For this, Smyth served time in Holloway Prison, occupying the cell next to that of Pankhurst’s. Even this seemed not to stifle Smyth’s spirit. However, visiting her at Holloway Prison in 1912, well-known composer Sir Thomas Beecham recounts a fantastic vignette of Smyth rallying the women in the midst of their incarceration:

“I arrived in the main courtyard of the prison to find the noble company of martyrs marching round it and singing lustily their war-chant while the composer, beaming approbation from an overlooking upper window, beat time in almost Bacchic frenzy with a toothbrush”.

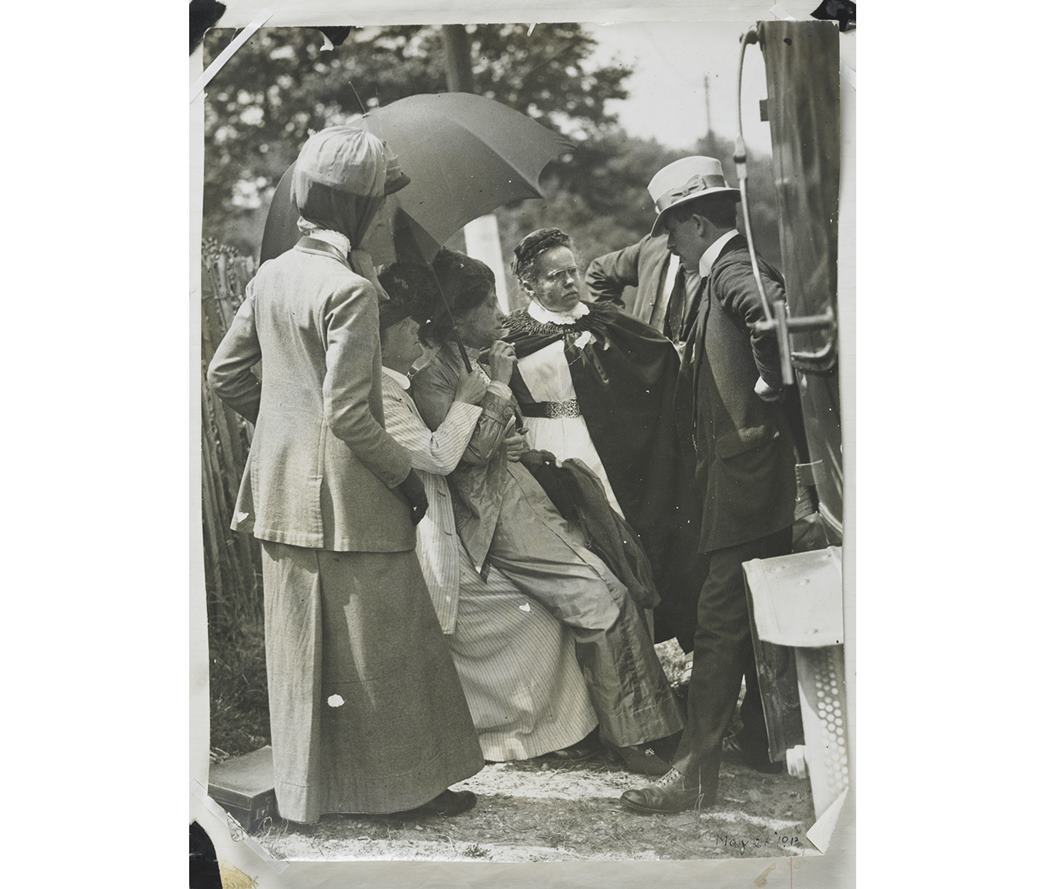

Nevertheless, prison records inform us that Smyth was released early from her sentence, citing the great strain that imprisonment had put on her mental health. She then went to her home in Woking, Surrey, where Pankhurst followed to recover when she, too, was released from prison. Pankhurst, who had participated in the hunger strike whilst imprisoned, was granted temporary release to recover her strength. A photograph of the pair together can be seen in the Museum of London, dated 26 May 1913, as the police arrive at Smyth’s home to re-arrest Pankhurst. We see Pankhurst supported on Smyth’s lap, the latter holding an umbrella to shelter an ailing Pankhurst from the sun.

This photo, on display in the People’s City Gallery, shows Emmeline Pankhurst being rearrested on 26 May 1913, whilst recuperating at Smyth’s home in Woking. Shading herself from the heat, Pankhurst is dressed in a grey suit and still weakened by hunger strike is here seen fainting back on the knee of Smyth. (ID no.: 50.82/1400)

Following her involvement with the movement, Dame Ethel Smyth published a flurry of memoirs to document her experiences as a composer and suffragette. It is here, too, that historians gain a greater insight into Smyth’s romantic affections. Women, and the historic queer community, were tacitly discouraged from disclosing the details of their sexuality for public consumption. This tends to hurt LGBTQ+ demographics as they look for their legacy in London’s history, but Smyth makes the job easier than most. Even as early as 1892, she had written to her friend and companion, Henry Barrett Brewster, proclaiming that “it is so much easier for me, and I believe a great many English women, to love my own sex more passionately than yours”.

Emmeline Pankhurst’s relationship with Smyth remains the subject of some debate among scholars. For her part, however, Smyth was hardly ambiguous when it came to documenting her affections for women. Impressions That Remained, 1919, was to be Smyth’s first memoir, and it would be succeeded by nine more in a mere 21 years. Among her infatuations and relationships disclosed in these writings, Smyth at the age of 71 met Virginia Woolf, and declared, “I don’t think I have ever cared for anyone more profoundly”. Woolf, in turn, did her part to disclose some hint at Smyth’s romantic life, proclaiming not only that Smyth had fallen in love with her, but that “In strict confidence, Ethel used to love Emmeline [Pankhurst] – they shared a bed.”

And remarkably, for all her ground-breaking accomplishments, and in spite of her controversies, Dame Ethel Smyth was knighted as a Commander of the British Empire in 1922. She became the first woman to be granted the damehood on the merit of her contributions to composition and publication. Her mark on London’s history as an activist; her professional accomplishments; and the fascinating series of reflections upon her romantic life offer some reassurance that Smyth will not lapse into obscurity any time soon.