East London is seen as the birthplace of Grime. As a highly accessible contemporary Black British musical genre, Grime has enabled young people to create a sense of belonging, as well as connect to a global audience.

‘It’s not just making a song, it’s building a scene.’ OSOM, rapper and poet

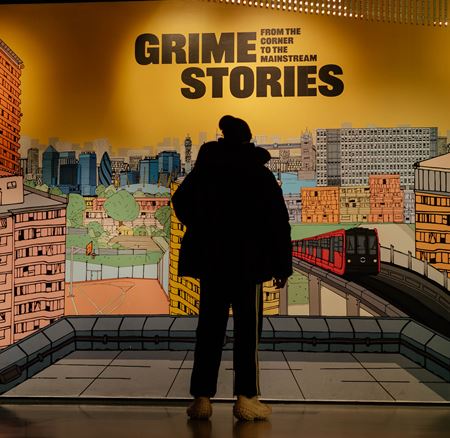

The Grime Stories display at the museum. (©Museum of London)

Since the opening years of the 21st century, the Grime music scene has been a key feature of east London life, particularly for young, multicultural communities. In these areas, music is often used as a lens to provide eloquent, thoughtful and candid reflections on everyday life. By now, many people are familiar with the pioneer narratives of Wiley and Dizzee Rascal. However, there are also many untold stories from those early days.

East London has been an area of social and economic disadvantage for many centuries. At the same time, it has been a site of movement and migration — from the French Huguenots, to Irish and Jewish settlement in the early 20th century followed by migration from the Caribbean, Africa and the Indian sub-contintent from the 1950s. For decades, east London has been characterised by a vibrant, and sometimes uneasy, multiculturalism.

In the contours of inner and outer east London — from Tower Hamlets to Barking and Dagenham — we often miss what has so far been a less-visible story of living, growing up and trying to flourish in places of deep poverty and disadvantage. A changing economic landscape from the late 1970s saw a steep decline in manufacturing. Like other disadvantaged areas, East London lost many local jobs. What is striking about these locations is that the City of London and Canary Wharf present a clear reminder of the UK’s financial wealth. What we do know for certain is how little of that great wealth trickles down.

The birth

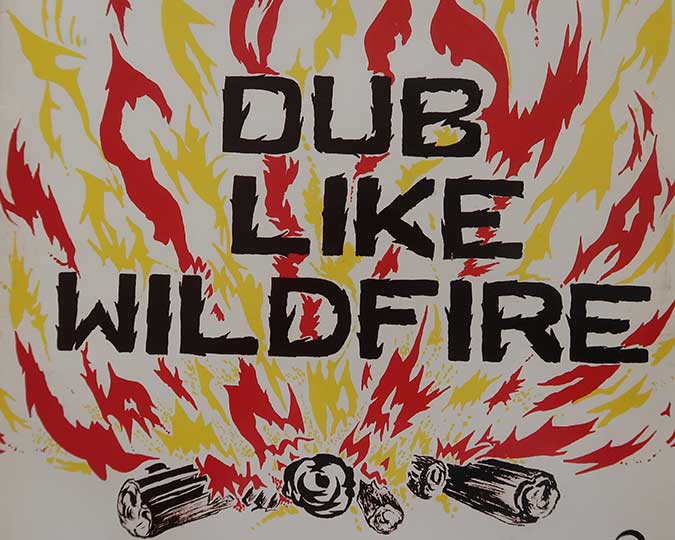

East London — particularly Newham and Tower Hamlets — is seen as the birthplace of Grime. As a highly accessible contemporary Black British musical genre, Grime has enabled young people to create a sense of belonging, as well as connect to a global audience. In those early days, on council estates, on street corners, in youth clubs and in schools, young people gathered to hang out and make music that mattered to them. Music that allowed them to narrate the conditions of their being, and to articulate their struggles, their joys, and their losses.

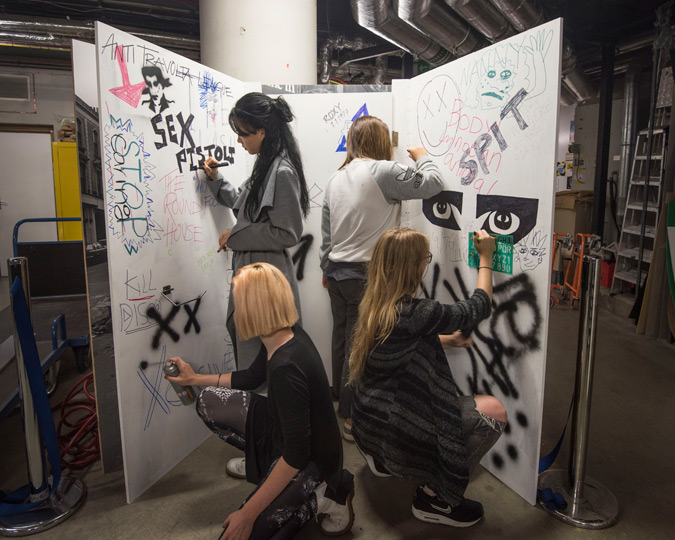

By using English accents, and therefore their own voice, Grime provided an opportunity to step away from the ‘elders’ in the UK Garage scene who, at the time, were not paying too much attention. At the same time, the commercial juggernaut that was US hip-hop and rap was subsumed, in London at least, by a black English aesthetic. It should not be too difficult to imagine the liberating aspects that occur in the creation of this liminal space — a scene where young people could talk about their hopes, dreams, challenges and aspirations.

A symbolic space

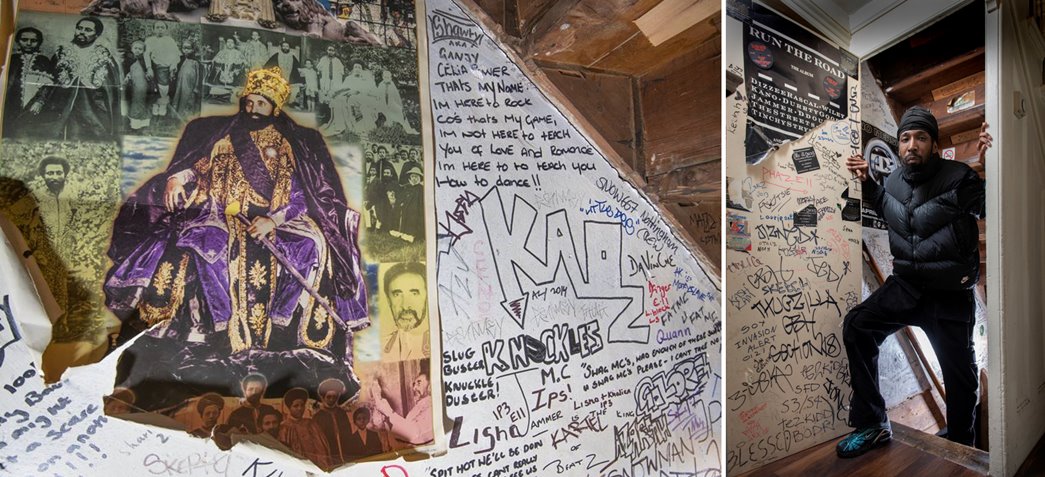

Plaque outside Jammer’s family home. (©Museum of London)

In the Grime scene, spitting bars acts a form of cultural exchange. The symbolic spaces of the crew developed out of a Jamaican sound system culture that was the sonic background for many MCs. Jammer’s basement in Leytonstone where many MCs and crews clashed and recorded is another symbolic (and physical) space. Youth centres and street corners where young people could congregate allowed for the development of creative clusters from which innovative musical practices, like Grime, could emerge.

Within this context, we can see the Grime crew as a symbolic space where groups of like-minded individuals, who share a common interest, in this case — music. Often there will be a familial connection and crews may include members who attended the same schools, grew up on the same estates, are brothers or relatives of some kind. Newham Generals, East Connection, Roll Deep and N.A.S.T.Y are past examples of influential Grime crews from the early days.

Gentrification vs regeneration

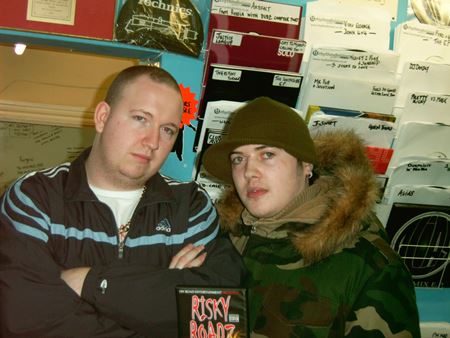

Rsky and Sparkie at Rhythm Division in 2005.

Rhythm Division was an integral record shop at

the heart of the development of grime. The shop closed and is now a coffee

shop. (Courtesy: Roony ‘Rsky’ Keefe)

A decade ago, the London 2012 Olympics promised a legacy of hope and opportunity for some of the most deprived areas in London and the UK. Four east London boroughs; Barking and Dagenham, Hackney, Newham, Tower Hamlets and Waltham Forest were hosts for London 2012. Try to imagine being a young person growing up in these areas over the last 10 years, knowing that what was promised has not been delivered.

Gentrification has been repackaged as regeneration, it occurs at sites of previous national and local disinvestment. Transformation of the social environment is highly desired by policymakers and planners. Often what we see in these spaces is a generalised middle class restructuring of place that results in the displacement of those without the economic or political power to resist. For young Black adults in poor communities, social housing estates effectively become sites of monitoring, surveillance, and curtailment, whilst better off communities are not subject to the disciplining of leisure activities or public space in the same way.

Regeneration projects have drawn wealthier communities into neighbourhoods that were previously seen, by some, as undesirable. However, in the production of gentrified urban space, separate spaces and places have replaced integration. The spatial barriers between rich and poor are evident in access to leisure, affordable housing, and the use of public space. Gentrification has amplified and intensified how young people from poor areas in east London are rendered out of time and out of place.

Music to one’s life

In newly gentrified east London people live with difference in a way that can be categorised as “separate together”. On the whole, the wealthier residents are removed from the daily realities of the urban poor. In these environments, we may not necessarily see ostentatious displays of wealth. Instead, there a number of sophisticated and subtle ways to convey status, including being able to buy or rent property at a price that is beyond the reach of most residents, as well as the capacity to participate in leisure pursuits.

Nevertheless, making and listening to grime, rap and UK drill continues to be a convivial and generative activity among the young. And, although these musical forms have been cited as an incitement to gang membership, criminal activity and violence particularly amongst young Black men, we can see how making music is a cultural, socio-economic, and political process that is resistant, enabling and joyous.

Dr Joy White is author of 'Terraformed: Young Black Lives in the Inner City'.