We take a look at how, over several centuries, the representation of Guy Fawkes has evolved from being a notorious criminal to a symbol of resistance.

In the past, 5 November, or Bonfire Night, was often referred to as ‘Guy Fawkes Night,’ or ‘Plot Night’. These names root the event into England’s often bloody history. In the decades following the Protestant Reformation of the 16th century, England’s Catholics were marginalised and faced persecution. Guy Fawkes was one of a group of Catholic men plotting to blow up the House of Lords during the State Opening of Parliament on 5 November 1605. Their aim was to assassinate the Protestant King James I and his ministers, and install his daughter, Princess Elizabeth, as a Catholic queen.

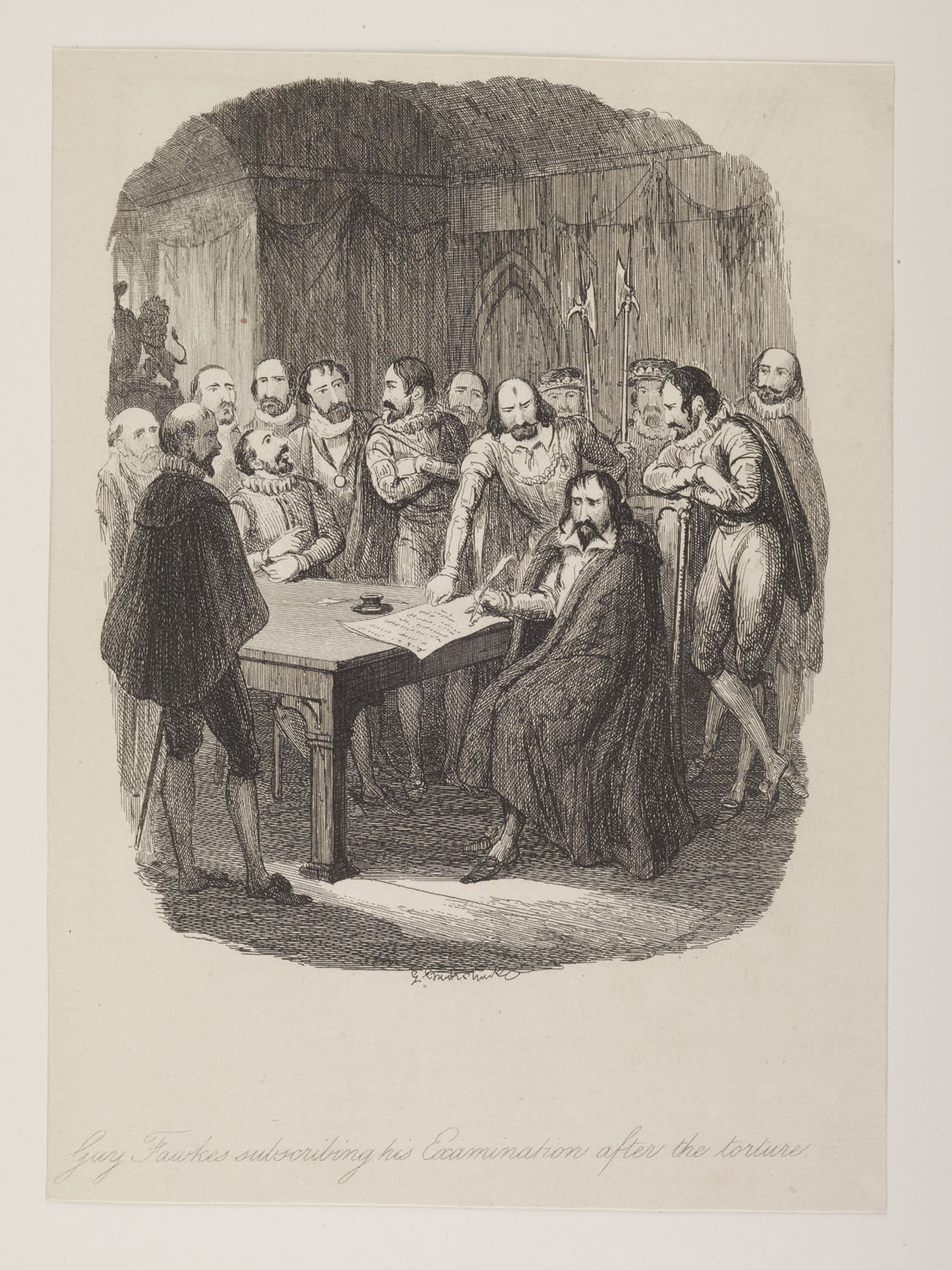

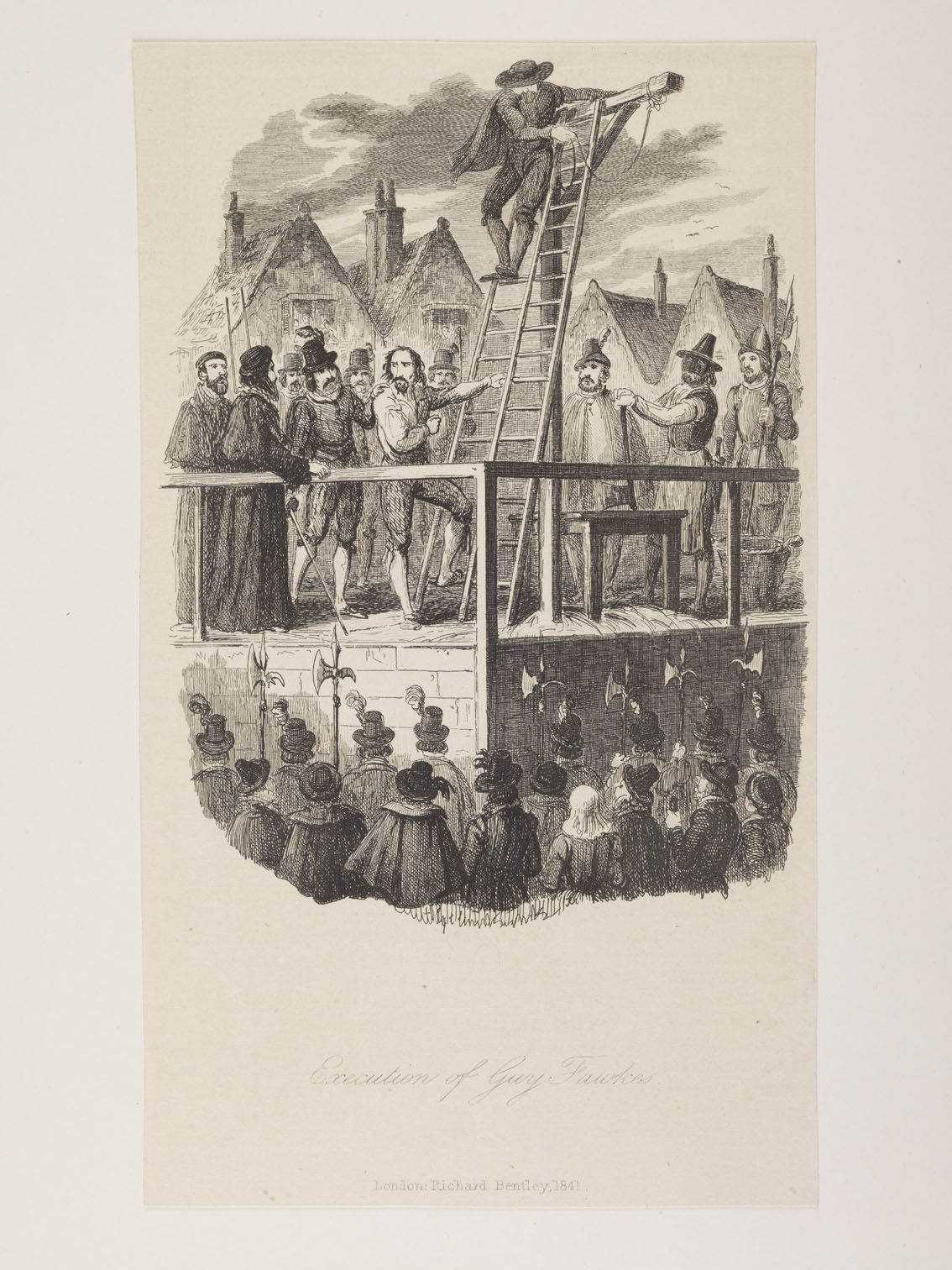

Due to his military experience, Fawkes was responsible for planting and detonating the explosives. But, there was a tip off, he was discovered, arrested and then tortured to extract a confession. Found guilty of treason, Fawkes and some of his fellow conspirators were sentenced to be executed on 31 January 1606 by the gruesome method of hanging, drawing and quartering.

(left) An oil painting by Arthur T.F. Clay showing the enactment of the searching of the crypt by the Yeomen of the Guard, 1894. And a theatrical portrait plate with engraving of the actor O. Smith as Guy Fawkes, 1844-56. (ID nos: 27.147, 99.132/189b)

The start of a tradition

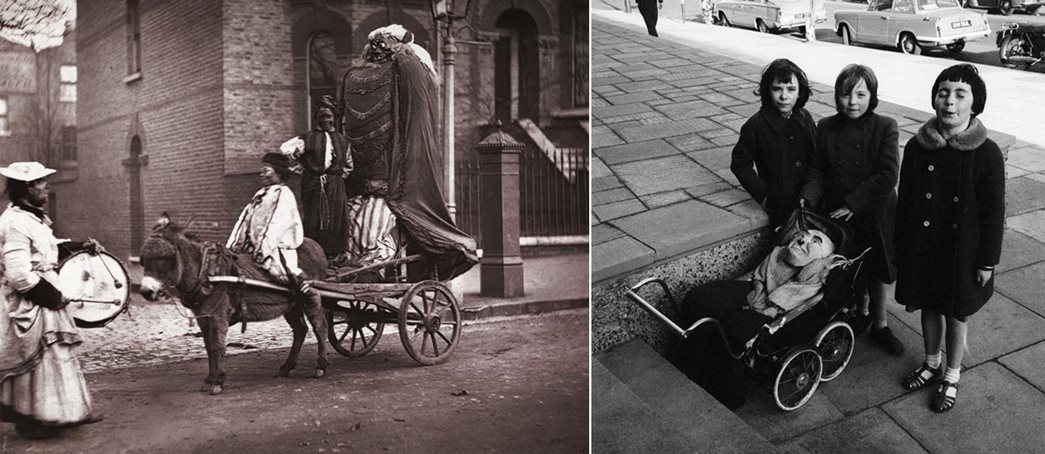

In 1606, to celebrate the failure of the plot, Parliament passed into law ‘An Act for a Public Thanksgiving to Almighty God every Year on the Fifth Day of November’. Bonfires were to be lit, and services and sermons delivered commemorating the event, making it an annual feature of English life. A custom also developed, in the run up to Bonfire Night itself. Children made effigies of Guy Fawkes from old clothes, pillows, newspaper, cardboard, or anything handy. These figures were wheeled round the neighbourhood, with the kids stopping adults to ask “penny for the Guy?” This was sometimes done to raise funds for a good cause but, more often, it was a ruse to earn some extra pocket money. On the night of 5 November itself, the effigies were ceremoniously burnt on the bonfires. Today the custom has largely died out, not least because it has been supplanted by Trick or Treating.

A tradition continued

(left) A c.1877 photo showing a ‘November effigy’ (sometimes of unpopular public figures like Guy Fawkes) being paraded through the street. And a 1962 photo of three girls with their Guy Fawkes effigy shows how the tradition has continued. (Courtesy: IN646; ©Henry Grant Collection, HG1541/73)

Immortalising Fawkes

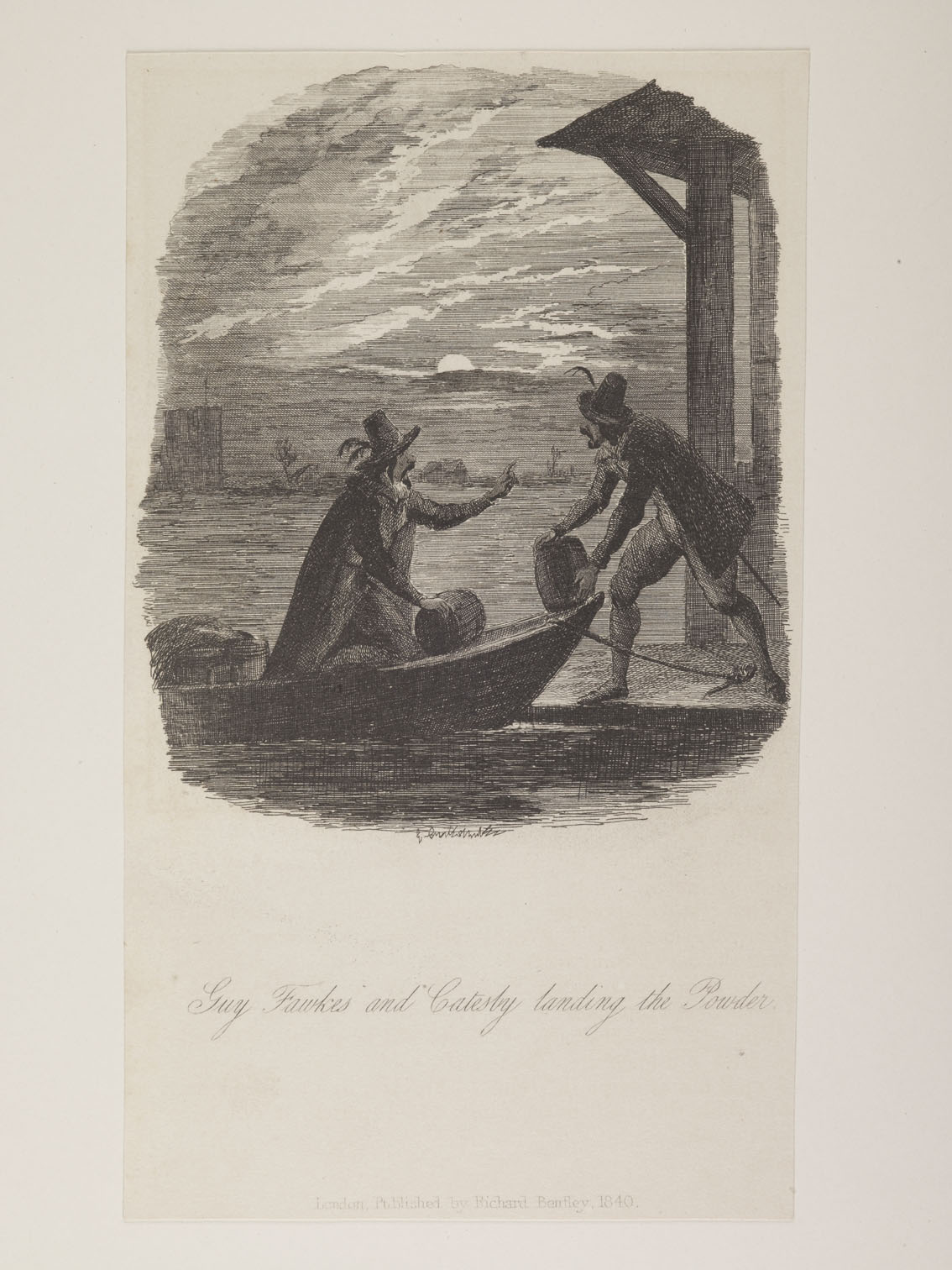

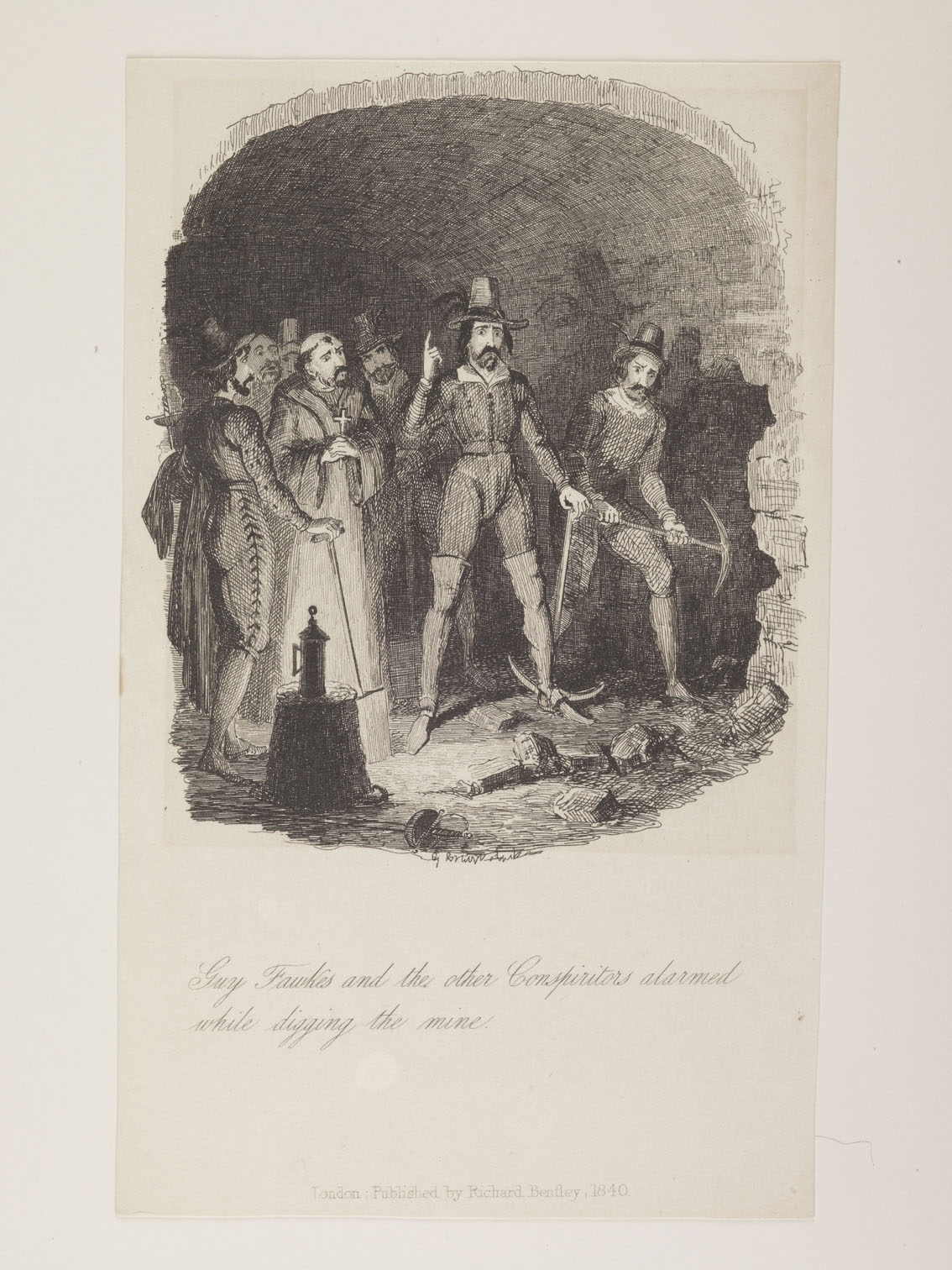

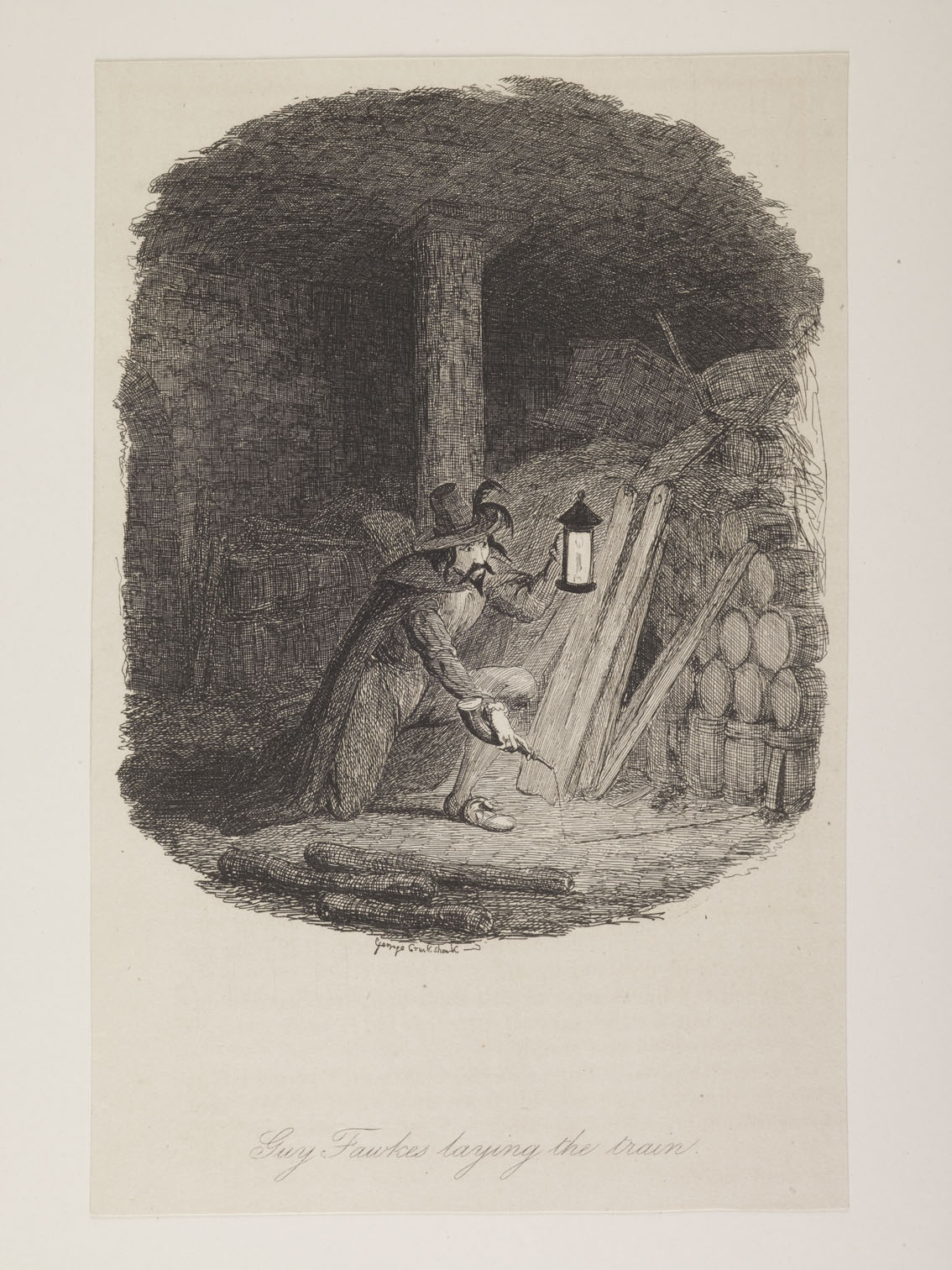

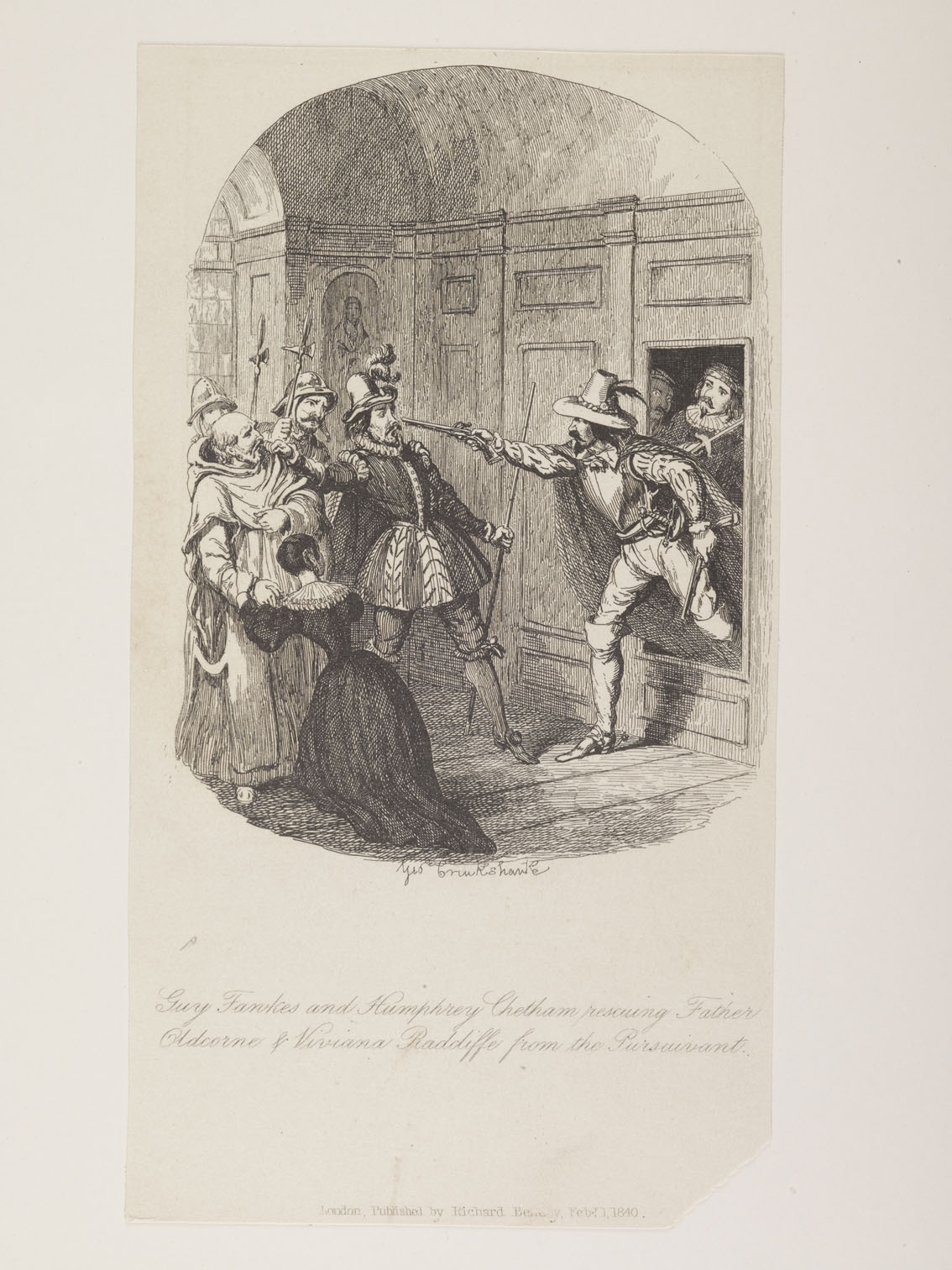

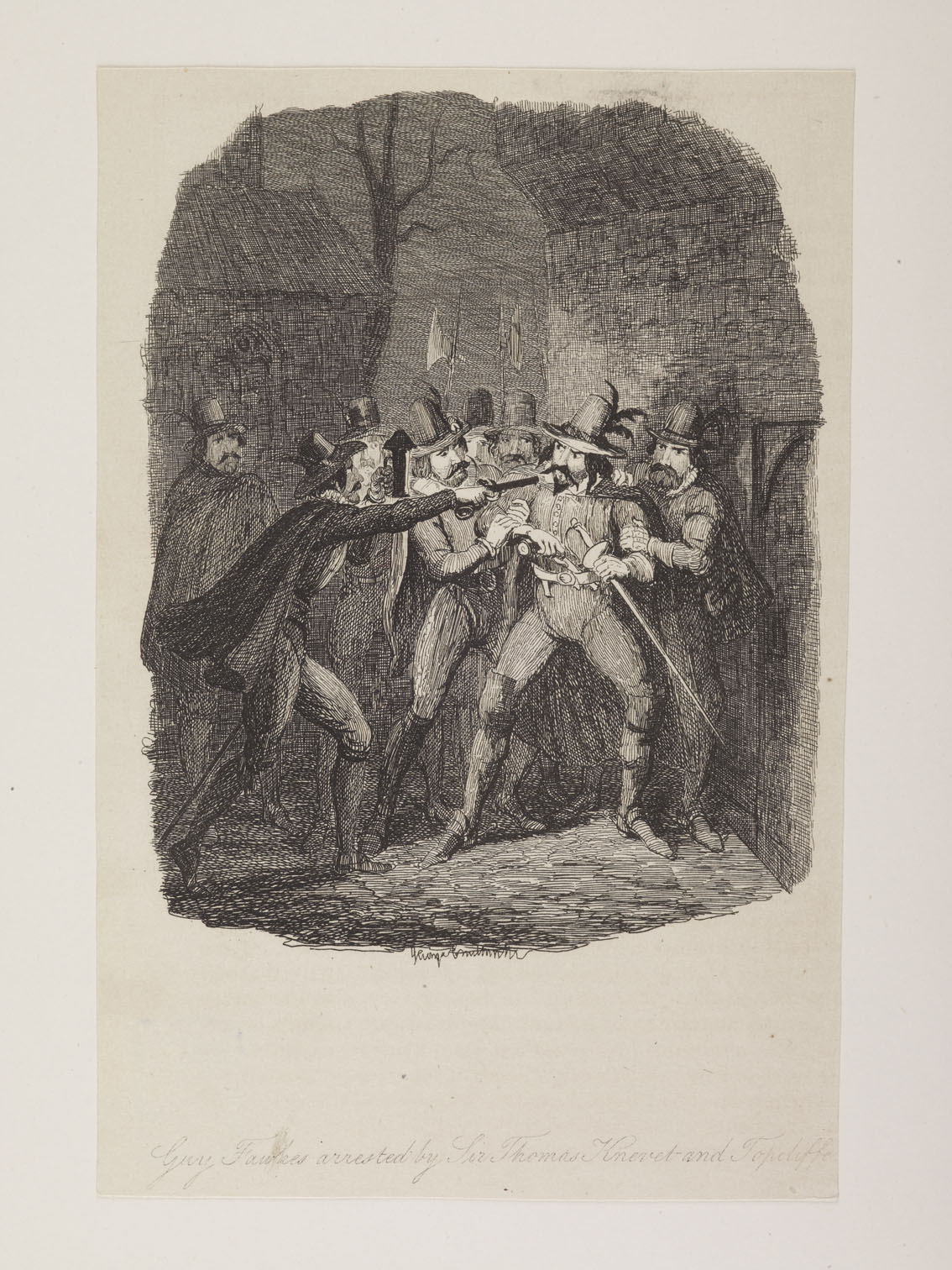

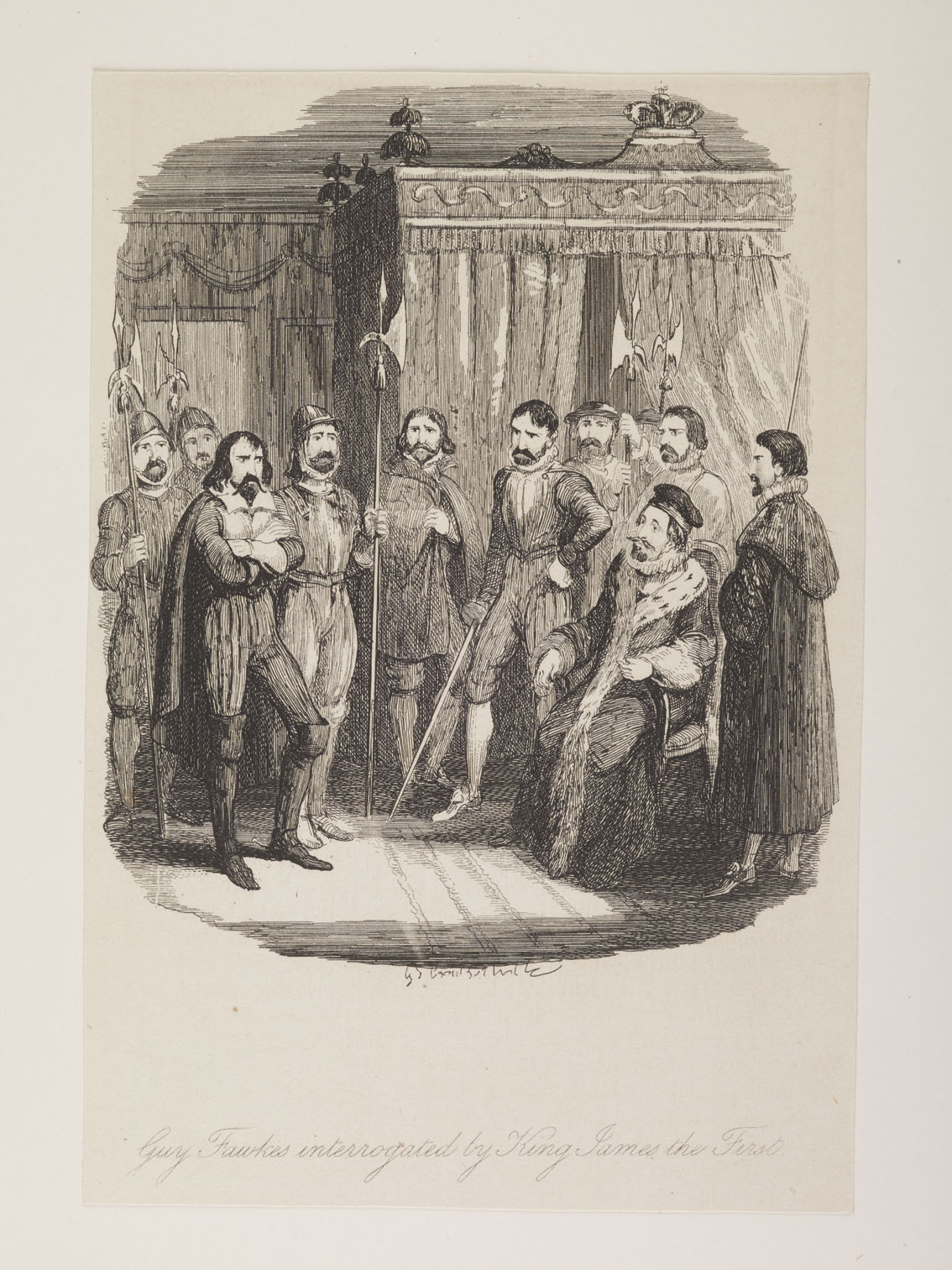

Guy Fawkes was not the leader of the conspirators. That role belonged to Robert Catesby. But it is Fawkes who became synonymous with the Gunpowder Plot. The others have been forgotten, except, perhaps, in the classroom. And, although he became a folk devil, to be burnt in effigy as a traitor on bonfires celebrating the deliverance from harm of James I, over time Guy has become, paradoxically, a figure of romance: a freedom fighter against oppression. William Harrison Ainsworth’s 1841 novel, Guy Fawkes, made a significant contribution to the redefining of Fawkes as less of a villain than a flawed anti-hero. Although largely unread today, the novel’s combination of historical fact, high drama and romantic embellishment made it a success at the time of publication.

George Cruikshank’s illustrations for the novel certainly helped visual the narrative and imprint events such as Fawkes’ torture or his meeting with King James on popular culture. Cruikshank worked as a caricaturist and illustrator, becoming the most celebrated satirical artist of his day. In the 1820s, Cruikshank had moved into book illustration, working closely with Charles Dickens. By the time he worked on Ainsworth’s 1841 novel, he was a well-known figure, sometimes known as ‘the modern Hogarth’. Among the museum’s collection of Cruikshank’s works are 22 etchings from the Guy Fawkes novel, illustrating the various events in what is now popularly called ‘The Gunpowder Plot’.

Significantly, in the wake of this popular novel, Fawkes began to appear in plays and children’s books.

A symbol of resistance

A mask acquired from the St Paul’s camp of the Occupy London movement in 2011. (ID no.: 2011.83/2)

In the 20th century, in Alan Moore’s 1988 graphic novel, and subsequent film, V for Vendetta, the character V, an anarchist, fights a tyrannous state wearing a stylised Guy Fawkes mask. David Lloyd, the original illustrator of V for Vendetta was explicit about his aim in drawing the mask, saying he wanted “to adopt the persona and mission of Guy Fawkes – our great historical revolutionary”. The image of Fawkes (or V) as a symbol of revolutionary protest has grown throughout the 21st century. Members of the Occupy movement wore similar masks during the global anti-capitalism protests around 2010. Online hacktivists, Anonymous, use the mask image in web forums and at in-person protests. Although inspired visually by Moore’s graphic novel, these groups nonetheless testify to legacy of the Gunpowder Plot in popular culture, and in particular, the figure of Guy Fawkes as a symbol of resistance against an oppressive state.