The museum’s collections hold a wide variety of headwear, dating from the 16th century to the present day. Here, we take a close look at four very different hats and the cap-tivating stories of the people who wore them.

From health to style and ritual, people have covered their heads for a variety of reasons. No wonder, then, that the Museum of London holds a vast and varied collection of headwear, dating from the 1500s to the present day. The latest audit recorded more than 600 of them! These include everyday work hats, fashionable caps and bonnets, those that have survived battles, and even those with hat-tricks. Here, we train the spotlight on four very different hats and the cap-tivating stories of the people behind each of them.

The slap-hat!

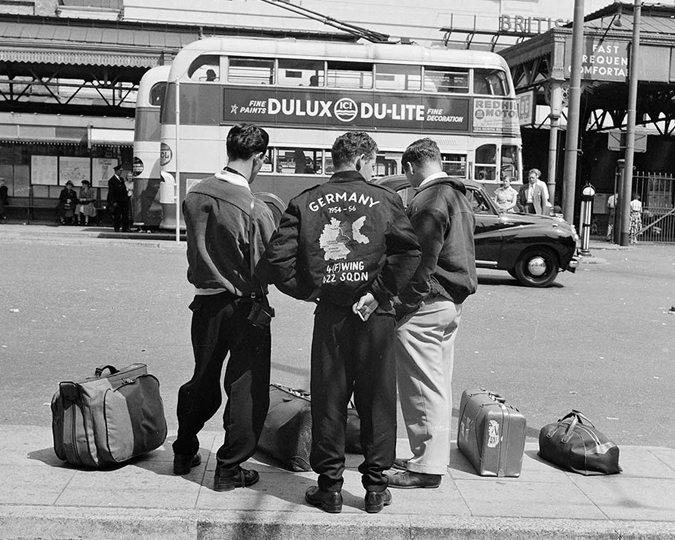

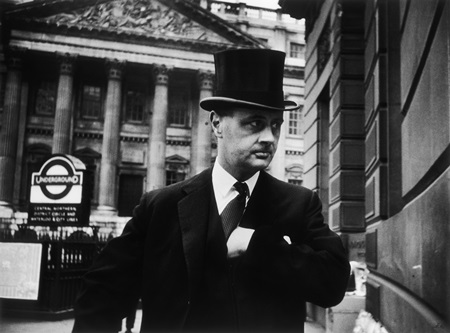

This is how the top hat would have looked, when worn, 1961. (ID no.: IN16496)

Combining practicality with elegance is what functional fashion is all

about. Much like the fold-down bicycle of today that allows a London commuter

to easily board a busy train, this collapsible top hat would have made life

easier for its wearer, Thomas Dickson

(1878–1972).

Dickson worked at the London stockbroking firm Pinn, Vaughn and Co. for an incredible 75 years, commuting by bus daily from his home in Streatham to his office at London Wall until the age of 95!

Whilst on first sight, the hat — made by Henry Heath, a well-regarded Oxford Street hatter — doesn’t appear particularly extraordinary, it holds an intriguing capability. When pressure is applied to the top of Thomas’ hat, its black silk sides collapse inwards, reducing its overall height to just a few centimetres.

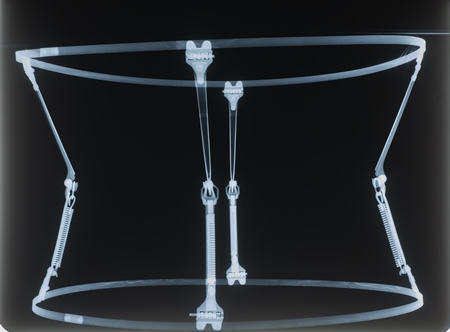

An x-ray image of a similar hat showing the internal mechanism. (ID no.: 34.50)

An x-ray image of a similar hat gives insight into how such a dramatic change is achieved. Concealed within the hat’s silk covering is a metal frame comprising two hoops joined by four hinged supports. The upper part of each support incorporates a spring that stretches when the hat is collapsed. Force applied to the stretched springs causes the hat to snap back open to full size. That an ostentatious tap was all it took to open up the hat gave rise to another name “chapeau claque”, or “slap hat”.

The invention of this type of mechanism is most associated with the Gibus family of Parisian hatters, who first submitted a patent for their design in July 1834. A setting where the ‘Gibus’ made its mark was at the theatre and opera. The tall dimensions of a traditional top hat were impractical for storing in a cloakroom or at a theatre seat. In contrast, the collapsible top hat could be stowed under a seat during a performance, leading to another epithet ‘Opera Hat’ for this type of headwear.

A chapeau claque with its case. (Courtesy: Hallwyl Museum / Samuel Uhrdin / CC BY-SA)

We cannot be sure if Thomas was a keen theatre goer, but from our records we know he “loved London and spent every spare minute when on his errands exploring its by-ways and churches”. So he could very well have frequented playhouses, and one imagines the hat was a practical option as well — easily portable on bus journeys around the city.

While Thomas Dickson’s hat equipped him for life and work in London, our next hat — while similar in style — tells a very different story. Made of hard leather, now cracked and containing several small holes, it belonged to a Royal Navy officer, William Gilbert Roberts.

Through the heat of battle

Born in 1791, William joined the navy at the standard age of 12, serving as a midshipman on the HMS Terrible. Life at sea was dangerous; when William was just 15 the Terrible was caught in a hurricane that lasted for a day and a half, losing its masts in the process.

Le Tonnant, at the Battle of the Nile (1798), by French painter Louis Le Breton. (Courtesy: ©National Maritime Museum, Greenwich, London)

On 14 December 1814, a 23-year-old Lt William wore this hat while serving on the HMS Tonnant in a campaign against the United States during the War of 1812 (1812-15). During one of the battles, William was shot at, and seven bullets passed through his hat. Although he suffered serious head wounds, he miraculously survived! Barely two months later, he found himself in danger again, when he was caught up in another storm, narrowly escaping before his boat sunk.

We know little of William’s life after this.

The hat ended up in the possession of his brother, Admiral John Roberts-Gawen (1787-1874). A label on it bears the admiral’s name, as well as a hand-written account of what had happened to his “beloved brother”, who had been “mercifully spared” from death. The hat and its bullet holes may have served as a reminder to John not only of his brother but also of the dangers of life at sea, which, as a fellow naval officer, he would have known only too well.

Family is also an important factor in the story of our next hat.

It’s all in the family

In the form of a soft, gathered circle, this hat is made of wool with a green warp and a dark grey weft. It is decorated with an embroidered motif on the top of the crown and trimmed with blue and green braid and embroidered flowers in blue, red, pink, green and yellow.

The hat is made of the same fabric as a suit in the museum’s collection, which was made in the early 1900s for the London-born artist Louisa Starr Canziani (1845-1909). In 1867, Louisa was the first woman to win the Royal Academy’s gold medal for history painting. The hat, however, was made in the 1950s by Louisa’s daughter, Estella Canziani, when she altered the suit for her own use. It is likely that the material came from offcuts from the original skirt.

Like her mother, Estella was a painter. In addition to this she was an interior decorator, and had a keen interest in folklore and tradition, writing on the working class costume and traditions of Savoy, a region of Europe incorporating parts of modern day France, Italy and Switzerland. These influences can be seen in the design of the hat, from the way that the material has been gathered with curtain tape to the vintage style — although made in the 1950s, it is more 1920s in design.

This hat is a lovely example of how clothing can be recycled and repurposed, in this case maintaining the link with Estella’s mother and their shared profession through its creation from her suit skirt — while at the same time bringing in more of Estella’s own personality and interests in the alteration.

A female familial bond is also at the heart of the creation of the final item of headwear explored in this article — a small, trimmed straw bonnet dating from 1875–90.

A bonny business

Elegantly trimmed with blue and brown silk ribbon, the smaller proportions of this bonnet is in keeping with 1870s and 1880s headwear fashions for women. It would have been worn on the back of the head, allowing much of an intricately styled chignon or bun to be visible.

A label in the bonnet’s lining reveals it was made by ‘Emelie’ on 246 Regent Street, London. Despite this French-sounding name, Emelie belonged to two Somerset-born sisters, Emily (1838–1913) and Rhoda (1841-1934) Wyburn. At the time the bonnet was made, Emily and Rhoda were well established hat makers. In 1861, in their early 20s, the sisters were already working as milliners in Bridgewater, Somerset. Their elder sisters had also worked as milliners, but left the trade upon marrying. For unmarried women like Emily and Rhoda, millinery was a trade that offered women the chance to gain significant self-sufficiency and independence.

An 1884 fashion plate from Myra’s Journal of Dress and Fashion, showing off the latest dress style, including the bonnet. (ID no.: 64.8/136)

Their move to London around 1870 is testament to the sisters’ successful enterprise. Presumably seeking the increased opportunities that operating in the Capital would offer, they were first located on Lupus Street in Pimlico, before moving to the prestigious and fashionable Regent Street in 1875.

Their central new address is printed on the bonnet’s label, alongside a coat of arms that signifies that ‘Emelie’ held a Royal Warrant. This meant the sisters were supplying hats to the Royal family, and most likely their clientele included members of the upper echelons of London society.

Emily and Rhoda ran their Regent Street shop for nearly 40 years. In 1911, Rhoda — aged 69 — was still recorded as working as a milliner and shopkeeper. Emelie’s success enabled the sisters to live an extremely secure and comfortable lifestyle. In 1890, they purchased Hadley Manor, on the outskirts of London, subsequently becoming well known for their charity work in the local area.

Today, Hadley Manor no longer survives, although a “Wyburn Avenue” is just a short walk away from the site it stood. Moving from small town milliners to creating hats for London’s high society, this bonnet is a tangible reminder of the long history of female entrepreneurs in England.

The stories of the hats held in the museum’s collections are inextricably linked with the lives of the people who made, owned, and wore them. Those we’ve covered here are only a fraction of the stories ready to be told, but if they’ve grabbed your (h)attention, you can discover more by exploring our Collections Online.

Header image: Hat designed by Philip Treacy for display on the Louisa Harwood mannequin in the Pleasure Garden (ID no.: SC230/6)