The public execution of King Charles I has captured public imagination for centuries. The Museum of London has several garments reputedly worn or carried by the King at his execution on 30 January 1649. We take a closer look at some of them.

Portrait of Charles I as a martyr king, c.1660-70. (ID no.: 46.78/539)

In any collection — public or private — items connected to the monarchy always generate great interest. The Museum of London is no different. Of the wide range of objects in the museum’s royal collection, the history of those allegedly associated with Charles I and his execution at Whitehall over 350 years ago is particularly intriguing. More so, since, according to former Museum of London curator Kay Staniland, they may be “the sole survivors of that cold January day in 1649 when English history took such a dramatic turn.”

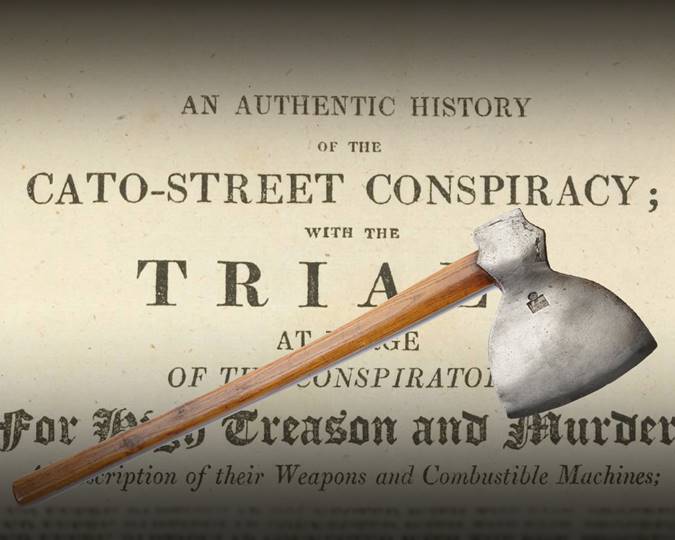

In an extraordinary act by Parliament, Charles I was tried and convicted of “High Treason and other high Crymes”. His death warrant was signed by 59 men, including Oliver Cromwell who later ruled the country as Lord Protector. The King was sentenced “to be putt to death by the severinge of his head from his body”.

But what was Charles I’s act of high treason?

In 1642, Charles I’s failed attempt to arrest five MPs for treason led to angry protests in London. The King fled the capital plunging the country into civil war, with royalist armies fighting those of Parliament. Held prisoner by Parliament, Charles I secretly arranged that a Scottish army would invade England to help him regain his throne. Parliament tried the King for treason and sentenced him to death.

He was beheaded on 30 January 1649 in front of the Banqueting House in Whitehall, before a crowd of men and women who had come to witness the extraordinary first state execution of a monarch in England’s history.

The location for Charles I’s public execution was hugely symbolic. The sumptuous Banqueting House represented the extravagance of Charles I, his oppressive rule and belief in the divine right of kings. The magnificent ceiling, painted by the artist Rubens, was a celebration of these divine principles.

An eyewitness claimed, as Charles was beheaded, “there was such a groan by the thousands then present as I never heard before and desire I may never hear again”. The reaction is particularly interesting as it was a crime to “speak, preach or write against” the King’s execution at the time.

Relics of King Charles I

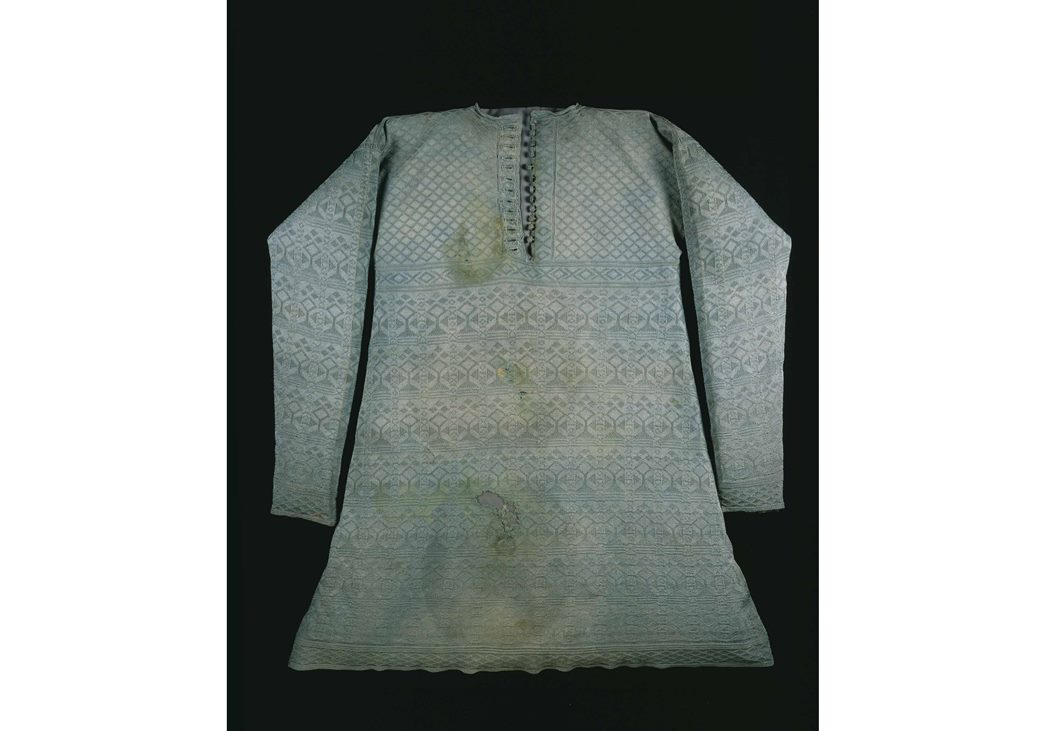

The Museum of London’s collection contains several garments reputedly worn by Charles I at his execution. Their material and style indicate they are of the correct date and quality to have been owned by the King, but we cannot be sure they were used on his final day, and some are currently being re-evaluated. There are conflicting accounts of what the King wore and who took the items after his death.

Thomas Herbert, the King’s attendant during his last two years, describes in his 1678 memoir how, on awaking on the morning of his execution, his master “…appointed that Cloaths he would wear; ‘Let me have a Shirt on more than ordinary,’ said the King, ‘by reason the season is so sharp as probably may make me shake, which some Observers will imagine proceeds from fear. I would have no such Imputation. I fear not Death!’”

The London Museum (the Museum of London’s predecessor) acquired the undergarment in 1924, along with a note claiming it had been worn by Charles I at his execution and “from the Scaffold came into the Hands of Doctor Hobbs, his physician who attended him upon that Occasion”. The vest remained in the physician’s family until the late 19th century, when it was sold and resold several times.

According to Staniland’s research, there are at least two linen shirts and a satin doublet that have been associated with the King’s execution. However, none has been conclusively proven to be genuine.

It has also been recorded that Charles I gave many small mementos to his companions during his last days. The museum holds several pairs of gloves, fragments of a cloak, a handkerchief and a silk sash reputedly owned by Charles I and gifted to loyal subjects.

The fragments are all that remain of a black cloak Charles I is thought to have given to his attendant, Sir Thomas Herbert, before he passed through a passage broken through the wall of Banqueting House onto the scaffold outside. One of Herbert’s daughters allegedly gave the cloak to Countess Johanna Sophia of Hohenlohe-Langenburg, who was based at the English royal court in the early 18th century.

The gloves too come with an interesting story of their own. These fine leather gloves with silver embroidery are said to have been given by Charles I to Bishop William Juxon, who accompanied the King to his execution. Several pairs of gloves have the same supposed origin. Embellished gloves like this were popular gifts. The wardrobe accounts of Charles I list more than 1,000 pairs of gloves suggesting he often presented them to others.

Contrary to the other ornate relics, the fine linen handkerchief in our collection is unusually plain for a royal accessory. However, it is embroidered with the King’s initials, “CR”, in red silk, and is said to have been carried by Charles I on the day of his execution.

The sash — made from silk and metal thread — is said to have been associated with Charles I but the connection to the King cannot be proven. Decorated with silver-gilt lace and spangles, the sash would have been a very expensive, high status item, worn across the body or around the waist, over a doublet or coat.

Memento mori

While these are some of the relics directly — and allegedly — associated with the King, it was recorded at the time that spectators dipped their handkerchiefs in the blood spilled from the scaffold. But what of those who did not witness the execution, or retained their loyalty to the King, despite his misdemeanours? The museum’s collection has a number of examples of memento mori, or mourning objects, including pendants and badges, either depicting a portrait of Charles I or with tearful dedications to his memory. One such example is of a heart-shaped silver locket with an inscription on one side: “Quis temperit/ A lacrymis/ January 30/ 1648” (meaning “Who can refrain from tears”) over an eye shedding three tears. On the other side is another inscription: “I live and dy/ in loyaltye” over an engraved heart pierced by two arrows.

Edited by Shruti Chakraborty, Digital Editor (Content). This article contains edited excerpts from Executions: 700 years of public executions in London, written by Thomas Ardill, Meriel Jeater, Beverley Cook and edited by Jackie Keily. Buy the book here.

Header image: Charles I after his execution with his head stitched on, British School, 17th century (ID no.: 46.78/537)

Executions closed at the Museum of London Docklands on 16 April 2023.

Explore the Executions online audio tour, which tells the fascinating stories behind some of the objects in our 2022-23 exhibition. The tour is a story of the executed, the Londoners who witnessed their deaths and the impact of public executions on the capital’s landscape, economy and society.