For our City Now City Future season, we're commissioning a series of essays on how London can survive the challenges of the next century. In this first installment, journalist Francesca Perry, founder of Thinking City, looks at how London can keep moving, and if our city will grind to a halt by 2100.

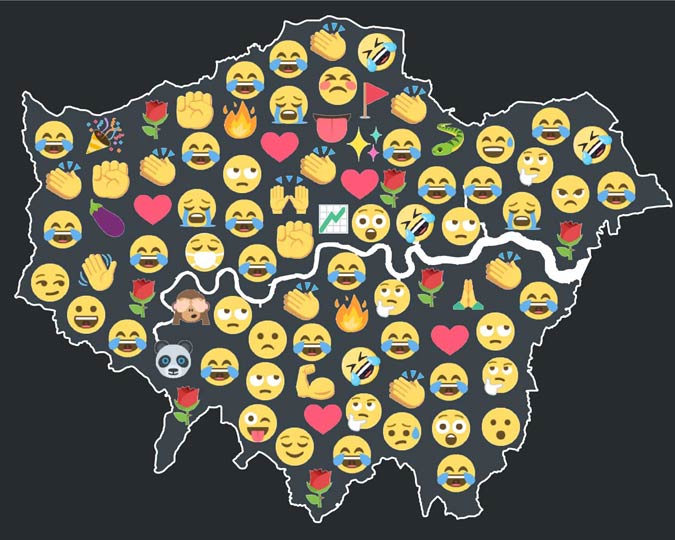

London grows by 10,000 people a month, and by some estimates we will hit megacity status of 10 million inhabitants by 2029. Without changing behaviours, modes or capacity, our urban transport system will cease to cope. But what could - or should - the future look like for how we get around the UK capital?

Choked streets

An omnibus and hansom cabs, High Holborn near Chancery Lane, 1902

Capturing the bustle of traffic in central London at the turn of the century.

Traffic in smog at night, 1956

© Henry Grant Collection/Museum of London

We’ve come a long way since the first horse-drawn bus in the capital in 1829: the city now boasts a bus network of 700 routes with 1.8bn annual users. The opening of the London Underground in 1863 sparked massive urban growth, and areas of London continue to develop as new stations are added to the 270 we already have. Private motor cars first appeared on the streets of London in the 1890s; some 120 years later, the pollution and congestion problems caused by cars in the city have reached critical levels. So might the future of London see a decline of the motor vehicle?

71% of Londoners never drive in the city, but the streets are still clogged with vehicles and journey times continue to grow each year, despite the 2003 congestion charge strategy aiming to limit the number of private vehicles in the city centre. There are roughly 5.7 million car trips made to, from and within London on an average day. Polluting vehicles mean air quality is dangerously unhealthy: over 60% of the air pollution monitoring sites in London broke legal annual limits in 2016.

Bikes, electric cars, public transport, and walking have all been championed as ways to address the city’s congestion or pollution problems. Daily bike trips are growing - cycle use in London increased by 63% between 2005 and 2015 - but the city’s cycle infrastructure still has a long way to go before it is truly safe. Segregated bike lanes are the exception rather than the norm; there are currently only six cycle superhighways, with two more on the way.

Electric cars might ease the capital’s pollution crisis, but congestion would remain the same. As it stands, fully electric cars only make up a tiny proportion of the cars on the road, but the UK has agreed to ensure that all new cars will be zero-emissions by 2050.

Design and efficiency improvements continue to be made to London’s public transport, but capacity is limited: the city streets would struggle to accommodate many more buses while new tube lines are prohibitively expensive.

Nowhere to go but down?

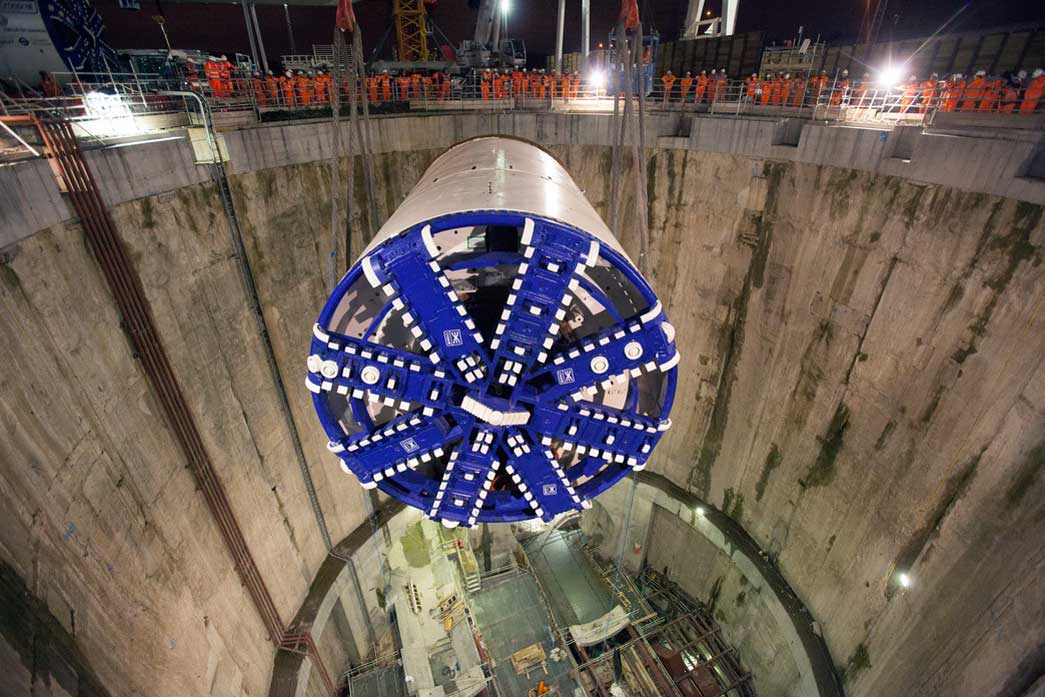

Crossrail (also known as the Elizabeth Line) aims to respond to this issue, increasing capacity in a streamlined way. The Elizabeth Line could enable people to quickly travel in to the city so they don’t necessarily need to live in it. Building on proposals for cross-London railways dating from 1941, the scheme was finally approved in 2007 and is due to open in stages from 2018. It will form a rapid east-west route across London and into the home counties, increasing central London rail capacity by 10% and carrying an estimated 200 million annual users (London Underground currently has 1.34 billion). Crossrail 2, the proposed route connecting southwest-northeast London and beyond, would open in the early 2030s if it goes ahead, and open the door for potential Crossrails 3, 4, 5 and so on.

Some fear Crossrail may not be enough to respond to London’s growing transport needs. The former head of Transport for London, Sir Peter Hendy, has predicted that the Crossrail lines will be "immediately full" as soon as they open, such is the burgeoning need for increased travel capacity in London. So do our transport plans need to be even more ambitious?

Pie in the sky

Photograph inside the Emirates 'Air Line' cable car

Photo by Romazur, CC BY-SA.

Radical ideas have been proposed over the years – to varied reception. In 1967, architect-planner Brian Waters - backed by the Conservative party - proposed replacing London’s buses with a monorail network in order to increase road space for motorists - but the plans vanished within a couple of years. Designs for a North Greenwich cable car at the turn of the millennium fell through due to fears over user numbers, only to be revived - and built - in 2012 by mayor Boris Johnson. As predicted, the number of people using the transport link is low, and figures suggest almost no one uses it for a daily commute.

Architecture firms have recently put forward novel ideas for the capital. Foster + Partners proposed “SkyCycle”, a 220km network of bike lanes constructed above overground railway lines, accommodating up to 12,000 riders per hour. NBBJ imagined transforming the Circle Line into a continuous giant moving walkway travelling at 15mph. Gensler’s “London Underline” involves turning abandoned tube tunnels into subterranean bike pathways. The CarTube, dreamt up by PLP, proposes a network of tunnels beneath the streets for automated cars.

Some of these have been supported - Network Rail and Transport for London backed SkyCycle - but others have been dismissed as unrealistic gimmicks. How, for instance, would we find the space under London to build an entirely new network of car tunnels?

A radical development that is becoming more realistic, however, is driverless cars – with some suggesting they will be widespread by 2050. In visualisations of a driverless car-filled London, people work or relax in sleek vehicles with picturesque views of a city apparently void of traffic, accidents, or even rain. But the addition of “robot cars” to the city would create new problems and require new kinds of physical infrastructure. Self-driving technology may be there, but it is not technology alone which changes people’s travel habits.

The future of transport in London needs to consider some key things: significant population growth, budgetary constraints, environmental sustainability, and public health and safety. It isn’t - and shouldn’t - just be about increasing transport capacity ad infinitum. Sci-fi visions of flying cars - or even just robot cars on the road - focus too heavily on vehicular and private transport. The fact is in the future we need to travel less, and when we do travel we need to take up less space by using bikes or public transport. Transport should tie up to new approaches to housing and work - people should be able to afford to live near where they work and walk, or work remotely.

Dream small

'Have fun on a bike!'

Bicyclists at Soho Fair, 1958. Roger Mayne.

Bikes take up far less space than cars, so promoting cycling and creating widespread safe infrastructure for it can only be a good thing. We could have more frequent, more affordable river buses on the Thames, ensure all vehicles on the roads are electric, and build more light rail - the most affordable way of increasing public transport capacity. Building roads is not the solution: the more you build, the more people will drive.

Many transport developments such as driverless vehicles tap in to the futuristic “smart city” vision, where disruptions and inefficiencies are eliminated from urban life. But life, and transport, is not problem-free. We should plan for a future of travel which is wise, sustainable and integrated, rather than completely radical.

Visit our free exhibition, The City is Ours, to learn how people around the world are learning to survive and thrive on our urban planet.

Watch out for more articles on the future of work, food, housing and freedom in London throughout the City Now City Future season, an exploration of urban living with over 100 events from now until April 2018.