The Museum of London is planning to pack its bags and move to West Smithfield. Moving house is always an exciting new start and when you scale that up to a museum of our size, the prospect is filled with possibilities. This is an opportunity to reimagine, reinvent and transform the Museum of London for its new home- West Smithfield, a site which has already seen some dramatic transformations over the years.

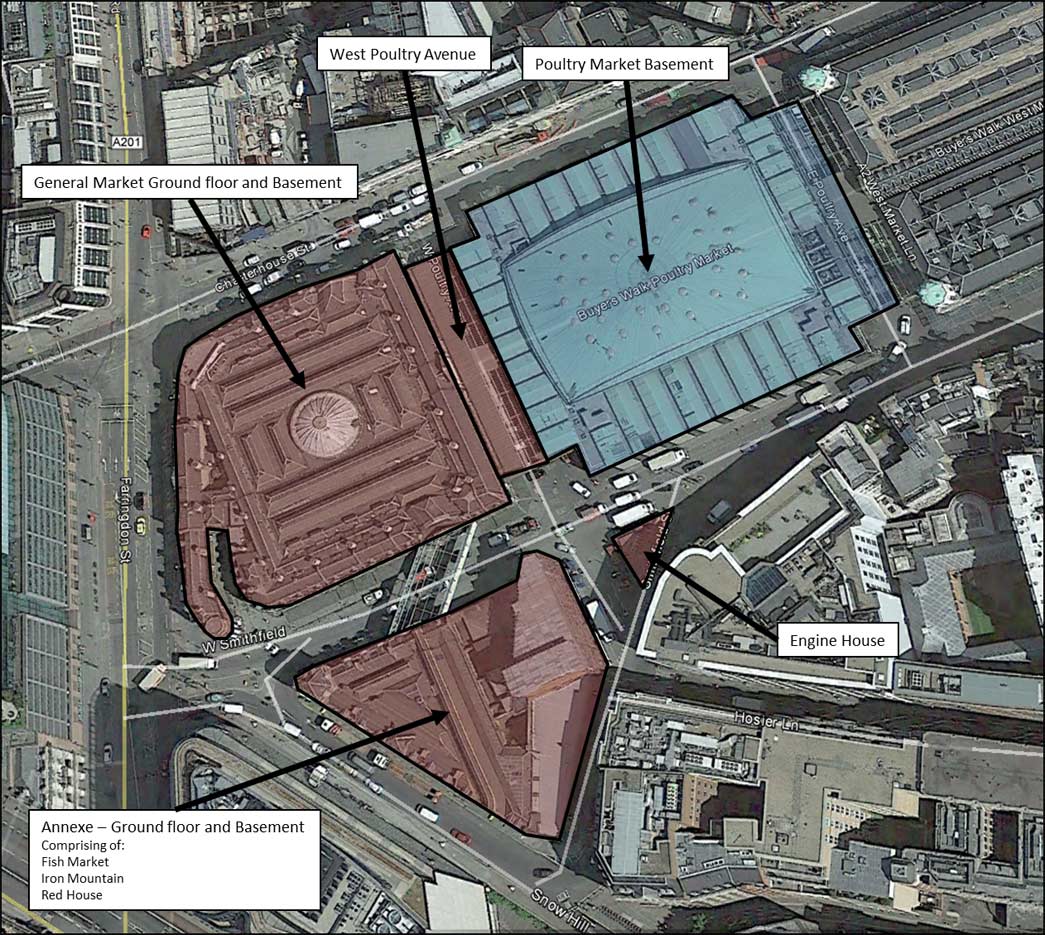

We are moving just half a mile to the west of our current location at London Wall. Our new home includes the Smithfield General Market (next to the Poultry and famous Meat Market) and also a suite of buildings known as The Annexe, which includes the Fish Market, Red House and Engine House.

First of all, the history of this site is extraordinary on so many levels. William Fitzstephen recorded a horse market at Smoothfield as far back as the 12th century. During the medieval period this expanded into an open air market selling livestock. In 1381 the City authorities banned slaughter of animals within the City of London, and the market moved just outside the City walls to Smithfield. Due to the presence of the livestock market more manufacturers and traders moved to the area, selling diverse goods to the crowds of people that were drawn to the area, often making use of the waste products such as the bones from butchering animals. The market moved under covers and by the 19th century its permanent buildings were constructed.

The market buildings were designed by Sir Horace Jones (the architect behind Tower Bridge, Billingsgate Market and Leadenhall Market). The first building completed was the Meat Market in the 1860s. Then followed the Poultry Market in 1875, the General Market in 1883 and finally the Fish Market in 1887 (Sir Horace Jones died in 1887, this was completed by Andrew Murray, Jones’ assistant).

The rectangular shape of the site containing the Meat and Poultry Markets was already established by the 18th century, and the buildings simply fitted into the space previously occupied by animal pens. The General Market was added onto the same alignment, but this was replacing the medieval street layout that ran alongside the River Fleet. The site also had the added complication of the Metropolitan railway running underneath, so Jones had to be creative with his design of the General Market.

Form meets function

Jones was innovative and experimental and his designs for Smithfield beautifully blended aesthetics and function. The creation of the General Market used cutting-edge Victorian technology. One part of it, the Red House, added to Jones's design by later architects, was one of the first refrigerated cold storage units in the country, powered by the adjoining Engine House. (Later on the small triangular Engine House was used as a public toilet, a slightly less glamourous transformation.) These principles of embracing the new and being daring align with our ethos at the museum, showing what a great pairing this is going to be.

The General Market was originally designed for the sale of fruit and vegetables, but by the time the building was completed in 1883 it opened as a fish market. By 1889 it transformed again, this time into an extension of the meat market. Little traces of its original function survive, such as the pineapple that sits atop the entrance on Charterhouse Street and also the collection of fruit on the pediment on West Smithfield. On the nearby Fish Market there are statues of boys riding on dolphins.

There are two architectural

elements to the General Market that cause it to stand out:

The Phoenix columns

Phoenix columns were a new development, patented in 1862; they are made from sections of wrought iron that were riveted together. This technique meant they were very strong, fire resistant and could withstand vibration. This innovation emerged from the Phoenix Iron Company, Pennsylvania, USA, thus the name.

Phoenix columns were crucial to the development of modern architecture. Compared with the loading capabilities of cast iron columns, Phoenix columns could take a far greater weight. Their strength and ability to withstand movement allowed the creation of more complex bridges, high railways and the development of sky scrapers.

The above qualities made the columns ideal for solving the

problems associated with the General Market site. Horace Jones used sixteen Phoenix columns

with connecting lattice girders to support the entire roof, creating the open

floor plan perfect for the safe movement of goods and people. Four of these columns span the distance from

the basement up to the roof. The columns

could flex and withstand movement, ideal for dealing with the vibration from

the railway. They were resistant to fire

and also corrosion as they could be painted and the interior of the columns

filled with concrete (this also helped to deaden sound).

Jones used 16 Phoenix columns with connecting lattice girders in the General Market to support the entire roof. 4 of these columns span the distance from the basement up to the roof. Phoenix strength meant that less columns were needed to support the roof, and created a very open internal plan. Although Phoenix-style columns were used world-wide, there seem to be only two known uses in this country, Smithfield and Redhill railway station. In fact, Jones didn’t even refer to them as Phoenix columns in his plans for the General Market. Perhaps he thought the City of London would reject this new-fangled American technology as untested, too dangerous to take a chance on.

You can learn much more about the curiosity of the Smithfield Phoenix columns in a report by Dr. Jenny Freeman, written for SAVE Britain's Heritage.

The Roofscape

Onwards and upwards, to the detail of the roof. Again Jones combines the practical with the pretty, there is a mansard roof, characteristic of the French influence on late Victorian architecture, around the outer edge. In the centre there are a series of louvres with a large central concrete dome.

Postcard showing Harts Corner in 1915

Inscription refers to the Japanese village, as Smithfield was nicknamed

This dome only dates back to 1953, before this there was a large wooden lantern-shaped structure. This looked like a Japanese pagoda and earned the General Market its nickname “the Japanese village”, later shortened to just “the village”. The whole design of the roof- the lantern, corner pavilions and the louvres and even the materials used- was intended to help the circulation of air and provide diffuse light, minimising direct sunlight that might spoil produce.

The roof trusses were made of laminated timber instead of ‘light iron’ because this would be cooler (iron would absorb and retain the heat from the sun). Jones was creating a large open space with a controlled environment year-round and a roof designed to effectively deal with rain and snow. Coincidentally this is similar to the requirements for a museum- except that instead of protecting delicate fruits and vegetables, we are preserving the city's history.

The final element is the floorplan. Jones was designing not just to ease the flow of vehicles but also to allow the movement of traders and customers around the space. Above ground the use of the Phoenix columns allowed for a large open space and below ground Jones built large basements to increase storage capacity, of course working around the railway.

Jones met all the tough practical requirements within the tight space available but he also carefully planned the aesthetic of all the market buildings and ensured they flowed harmoniously together and had a visual impact. He continued the use of red brick and Portland stone across the market buildings, and also added the embellishments of the pavilions, pediments, dormer windows and statuary in a style known as French-Italian Renaissance.

The Second World War

Unfortunately, Jones’s beautiful market design has not survived unscathed. World War II brought about a dramatic transformation. At 11:30 on the 8th March 1945 one of the last V2 rockets to hit London struck the corner of Charterhouse Street and Farringdon Road. The rocket blasted through Harts Corner and went through to the railway tunnels. The bomb had one of the highest casualty rates of any V2 attack: 110 people died and many more were injured. The surviving section of the Harts Corner was subsequently pulled down, and later the corner was rebuilt and Jones’ pavilion and entrance stairs were replaced with a modern concrete structure of modern, clean lines and uncluttered appearance.

The Fire at Poultry Market

Smithfield’s next major transformation came about due to a huge fire, which destroyed Jones’ Poultry Market building on 23 January 1958. The fire raced through the complex of basements and swiftly escalated because of the fat-soaked matchboards. It burned for 3 days and 1,700 firefighters fought to get it under control. 2 firefighters lost their lives and many more were injured. The flames shot up through the market building and caused its total destruction.

The Poultry Market was rebuilt in 1962-3 with the striking roof that currently stands. The roof was the largest clear spanning concrete dome roof in the world when it was constructed. The colour echoes the copper-tiled pavilions on the corners of Jones’s markets. It also visually links with the concrete dome that was built on the General Market in 1952.

What's next?

The buildings are currently in a terrible state with huge amounts of damage and rot, a lot of work will have to go into the buildings just to make them safe and then there will have to be the modifications to transform a market site into a museum.

The architectural competition for the new museum has now closed and we eagerly await the next transformation of this space. Whilst this next change has a wealth of exciting possibilities, the museum is also approaching Smithfield General Market as part of our collections; we will curate, conserve and continue to research these amazing buildings.

Learn more about the Smithfield site.