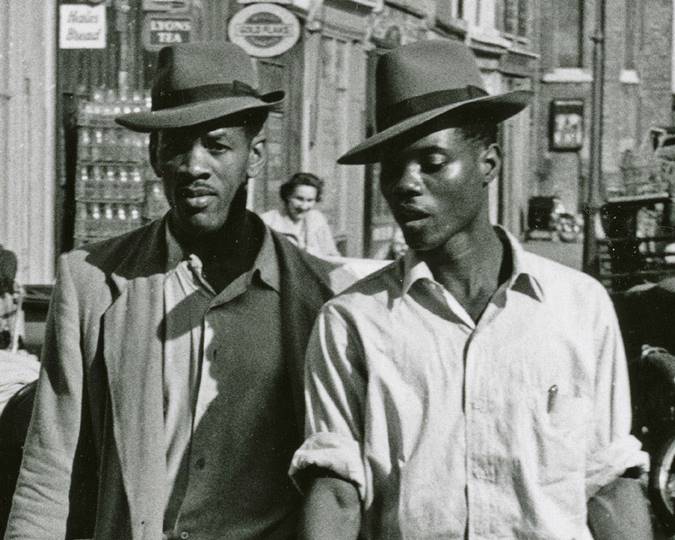

They’re not just hand-me downs, each strand threads a story with it. Be it a child’s dress made from her mother’s wedding gown, or one that has a legacy of multiple generations spanning 140 years, upcycled clothes have wonderful lives of their own! We showcase five lovely stories from our collection.

Many of us, especially those with larger families, have been on the receiving or giving side of outgrown clothes that — once refitted — are given a second life. Add the practicality of that to greater awareness of the environmental impact of fast fashion, and we are encouraged to seek more sustainable alternatives when adding to our wardrobes. The Museum of London holds many examples of altered garments in its collection, including those that have been completely remade from an existing piece of clothing. We focus on five ‘recycled’ garments, concentrating specifically on children’s clothing, a category that is a particularly rich source for interesting and ingenious renovations.

A sporty nightdress

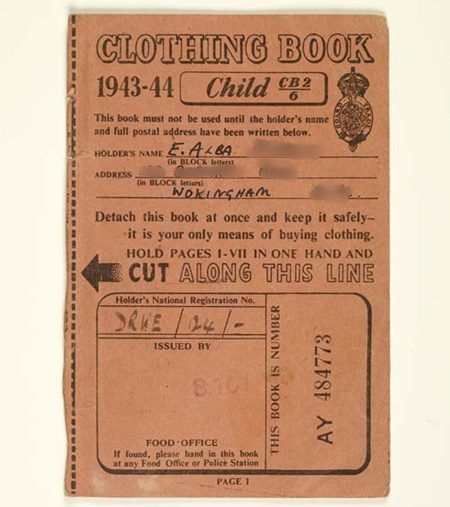

Child's clothing ration book for 1943-1944. (ID no.: 76.81/19)

This child’s nightdress was made in the early 1940s, a period when the impact of World War II made repurposing old clothes a necessity. With many textile manufacturing spaces being adapted to producing uniforms and military textiles, etc., the capacity to produce civilian clothing was severely limited. Alongside clothes rationing, the government-backed “Make do and Mend” campaign was launched in 1943. It promoted guidance on how to make clothing last longer, fabric care and repairs, as well as advice on making new clothes from ‘tired and worn garments’. The campaign was heavily marketed, and altering an adult’s clothing to create children’s garments was frequently suggested. Ideas in Gertrude Mason’s 1945 guide NewLife for Old Clothes include making a child’s dressing gown out of an old winter coat, and a detailed tutorial on creating two boy’s suits from a used dress.

In keeping with such transformations, this nightdress — made for a young Jeanne Clarke by her mother — has been fashioned out of an old Viyella sports shirt. A trademarked cotton and wool blend, Viyella was well-regarded for its comfort and, therefore, an appropriate choice for sleepwear. The clearest evidence of the nightdress’s structural renovation is at its sleeves, where prominent hand stitching is visible across the shoulder seams.

The original machine-made sleeves would have been unpicked, recut to the appropriate length, and re-hemmed at the cuff before being hand-stitched at the shoulders. It is likely that the garment had been shortened at the hem too, and the yoke (the horizontal panel at the top of the bodice — typical of nightdresses) was added later. Its collar has been carefully hand-embroidered with a floral design in pink and blue. Trimmings were encouraged as a simple and effective way to update a garment giving “a freshness to a tired or out of date garment and a note distinction to a remodelled one”, wrote Mason.

Legacy shorts

A surgeon’s cut

These shorts (right) for young Mark were made from his famous surgeon uncle Cecil Rowntree’s gown in 1948. Portrait by artist T.C. Dugdale. (Image courtesy Manchester Art Gallery; ID no.: 2010.2/12)

This pair of white linen shorts with integral cross braces were made a couple of years after WWII ended, in 1948. Clothes rationing, however, continued until March 1949 and these shorts are very much in keeping with the ‘make do and mend’ ethos. They were sewn for four-year-old Mark Rowntree by his mother Barbara, using fabric from the surgeon’s gown of Mark’s uncle, Cecil Rowntree, who had died in 1943.

It’s a garment that mixes practicality with poignancy, using fabric inextricably linked to a career Mark’s uncle had excelled in. Rowntree (1880-1943) had a long and distinguished career in medicine, qualifying in 1902 and going on to work as a consultant surgeon at the Cancer (now Royal Marsden) Hospital, London. He served as medical officer to the Queen's Westminster Rifles during WWI and was a senior, later emeritus, surgeon at the Woolwich and District War Memorial Hospital.

White, while not the most practical colour for a young boy’s outfit, was standard for hospital gowns at the time. It was considered the easiest colour to clean and was also favoured for its connotations of hygiene. Nowadays darker colours, such as blue and green are used for surgeon scrubs to avoid eye-strain in the bright, white environment of an operating theatre.

The fabric’s heavy weight, necessary to withstand the frequent high temperature washes required to sterilise hospital linen, made it a hard-wearing material — well-suited to withstanding the activities of a young child! The unstructured, voluminous nature of a surgeon’s scrubs meant little unpicking of seams would have been required, offering Barbara plenty of fabric out of which to fashion her son’s new outfit. Nevertheless, the very narrow hem implies the material had been used carefully, with none going to waste.

Heart on her sleeves

Family is also at the heart of our next garment — one of two children’s dresses fashioned from a single dress sleeve! This 1860s girl’s dress of white watered silk, profusely trimmed at the hem and neck with blue ribbon, was made for a five-year-old girl from the sleeve of her mother’s wedding dress. An unusually placed diagonal seam across the back of the skirt and a triangle shaped insertion at its front hints at the dress’s former construction. However, these seams are cleverly concealed beneath an overskirt comprising panels of embroidered white net. Whilst there is a practical element to the dress’s reuse of fabric from a garment that is by its very nature single use, this is superseded by the symbolic and sentimental value imbued in the wedding’s new incarnation — a material link between mother and child.

While it may seem surprising that a whole outfit, even one for a young child, can be made from just one sleeve, the voluminous puffed sleeve — which was the fashion at the time — provided ample material. This 1905 brocaded pink silk dress with pearl button fastenings comes from the sleeve of a 1890s dress. The 1890s saw a revival of the large ‘gigot’ or leg-o mutton sleeve, gathered towards the wrist and often expanding past the shoulder in a balloon-like silhouette.

Just like today, fashion is cyclical, and the gigot had been in vogue some 60 years before, during the 1830s. Fashion historian and former Museum of London curator Valerie Cummings commented that by 1895 the gigot was “monstrous”, requiring 2.5 yards of material before immediately falling out of favour in the mid-1890s. Perhaps, this child’s dress was seen as an opportune way of reusing good quality fabric when the original garment’s design was no longer fashionable.

140 years in the making

The value and quality of a garment’s fabric is integral to the story of our final garment — a girl’s party dress worn in 1927 by 13-year-old Celia Henderson, made by her mother Sylvia. It is machine sewn, but hand-finished with trimmings of black velvet ribbon and gold and black rosettes at the neck, cuffs and waist. The dress’s slightly dropped waist and gold and black colour scheme are certainly 1920s in style. On closer inspection, however, it is apparent that the fabric, which is brocaded with small sprays of widely spaced pink and white flowers, is much older. The dress was actually made from the “very wide skirt” of an 1840s dress worn by Sylvia’s aunt Mary. Yet the material is older still, for it is, in fact, a 1780s Spitalfields silk. That gives Celia’s dress a lifespan of 140 years!

Spitalfields had been at the heart of Britain’s silk-processing industry in the 18th century. The arrival of skilled French Huguenot weavers to the area in the 1680s had accelerated London’s already flourishing silk trade. However, by the 1840s, when Celia’s Great Aunt had the fabric made up into a dress, the hand-weaving industry was in decline. Industrialisation and increasing foreign silk imports meant Spitalfields silk no longer commanded market dominance as before. Yet, the quality of the material was highly valued well into the 19th century. Additionally, for a dress with a highly structured silhouette, a crisp silk such as this would have been a more appropriate choice than a manufactured fabric with more drape.

Eighty years later, it must have been incredibly exciting for Celia to wear an outfit made from a material with such a long and important history, passed down through several generations of her family. While we might not all be as lucky to have a 140-year-old fabric at home to fashion ourselves a new outfit from, we hope that these garments have given our readers with a creative streak inspiration for their next project.