Meet the women behind ‘Weaving London’s Stories,’ a project delivered by the Museum of London in partnership with the Osmani Trust in Whitechapel, capturing the experiences of British Bangladeshi women and children in Tower Hamlets in relation to dress and identity.

‘Weaving London’s Stories’ is part of ‘Curating London’, a programme at the museum collecting objects, photographs and oral history interviews to represent the experiences of Londoners today. A key part of this work is ensuring the museum collection is as representative as possible of the experiences of the wide range of people who call London home. This includes identifying current gaps in the collection and delivering collecting projects to fill those gaps.

After engaging with local women and children through a series of activities, events and workshops, the museum collected 23 items of clothing and jewellery, 4 photographs and 17 oral history recordings which explore how different generations of British Bangladeshi women negotiate their relationship with traditional and non-traditional South Asian dress. The oral histories collected also explore a variety of other themes present in the lives of participants, including family life, cultural traditions and experiences of migrating to London.

The project begins to uncover similarities and differences in the views of those involved, including how some people’s dress is influenced and inspired by their cultural identity, whereas others define who they are by choosing not to wear traditional South Asian dress. One participant in her early twenties shares how important wearing a headscarf is to her own identity.

Q: Mmm. Is there anything in particular that stands out for you, that you think is part of your identity now.

A: Mmm. [pause] Like clothing items?

Q: Yeah.

A: I mean, I guess the most obvious thing that would come to mind is the scarf, because that’s you know, like I’ve been wearing that since I was eleven. So even - like I don’t always think about it, because I’ve just been wearing it for so long, but obviously nowadays there’s like lots of talk around like the Hijab and like Islam in general, so there is more attention drawn to it. Erm, and I think that does mark me out as having, maybe a different identity to, like, people who don’t, erm or people who wear it differently, because obviously I wear it a certain way, other people will wear it more like a turban, or like loosely or something like that. So, it’s just like a piece of fabric right but it is an interesting part of obviously one’s identity, including my own.

"I’ve always been interested in Zardozi, that’s just anything that’s Zardozi"

Lothfa has lived in Tower Hamlets her whole life, first on Brick Lane before moving further into Shoreditch. Here she describes her experiences growing up with her five siblings.

We used to go to school and straight after an hour later when we came home we used to be packed of the Bengali school, where we learned Bangla and then after we came home we’d eat and then an hour later we'd be off to Arabic school and we'd be home at nine o'clock and then it, then it meant one hour telly and then we'd be off to sleep and that was our daily routine Monday to Friday, and Saturday Sunday we’d spend with our cousins and our family. So I have four sisters and one brother so it was quite a big family and, you know, we're really close although we fought a lot and I remember my mum always telling us that, you know, she couldn't afford us like clothes and stuff and she would go past the shops and she would look at dresses and she'd be like, oh, you know, and then so when she took up being a seamstress, she'd be working like all hours of the night, the morning, you name it. She was just always on that sewing machine and what she'd do is she'd buy curtain fabric and she sewed us like jackets, dresses and stuff and everyone was really jealous of our dresses. Well, I remember going down Petticoat Lane Market and we had like Japanese or Chinese tourist surrounding us and taking pictures, because those five little girls wearing the same coat in floral curtain fabric [laughs]. So yeah, I do, like I remember having a really happy childhood, and then when, when we went to Bangladesh in year seven, when we came back from Bangladesh, we've moved houses to Shoreditch and that's when we moved away from like such a really close-knit community. To coming from that to Shoreditch which was, you know, a very mixed area. Where we lived it was 99.9% Bangladeshis where I went to school was 99.9 Bangladeshis we were always surrounded by Bangladeshis, so it was like this comfort zone that I came out of and when we went there, we experienced quite a bit of racism, you know, real shock like, you know, like I've never experienced this before, but yeah, no over the years they've gotten used to us and you know we’re bit more friendly now, but yeah it was like a huge like culture shock and it’s in London. Shoreditch and Brick Lane is like just a stones throws away, but yeah.

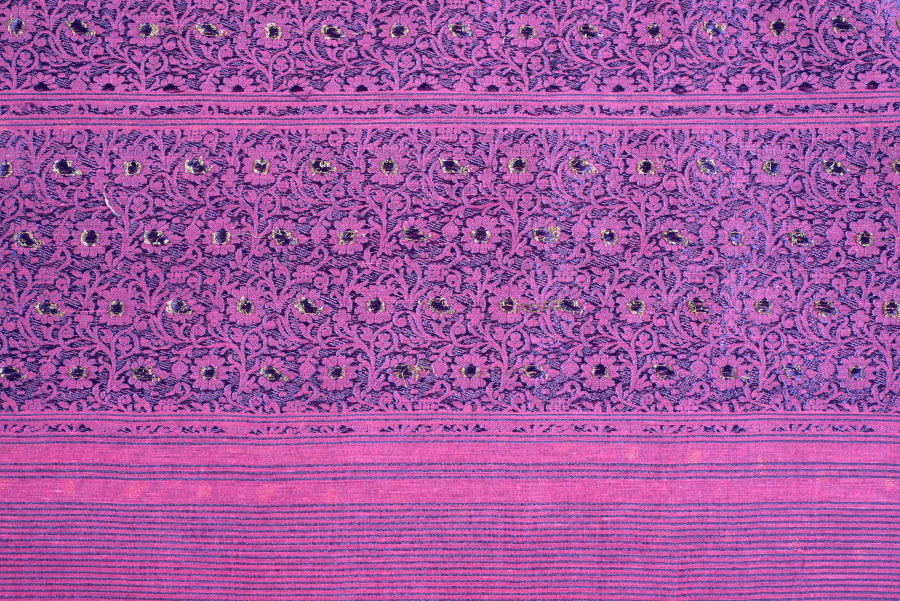

Close up of decorative zardozi embroidery on kameez

Lothfa donates a salwar kameez decorated with Zardozi, a type of embroidery using gold and silver threads to make designs on cloth. The outfit was worn by Lothfa on the third day of her wedding ceremony. On this day, it is tradition for the newlywed couple to visit the house of the bride’s parents, giving chance for the groom to bond with family members. Lothfa’s oral history recording describes her experiences of the wedding ceremony, explaining the different activities traditionally undertaken on each day. On the second day of the wedding Lothfa took part in a fish cutting ceremony, fish is an important part of Bangladeshi culture and cuisine. In this ceremony, the couple act out a scene in which the bride cuts up a fish purchased by the groom, which is then cooked and eaten by the couple and family members.

"My favourite items of clothing are still wearing jeans and t-shirts and tops with trainers. Because it’s comfortable, it’s practical, I can do whatever I need to do. Also I can be taken seriously, so people aren’t concentrating on what I’m wearing, it’s not distracting them in any way."

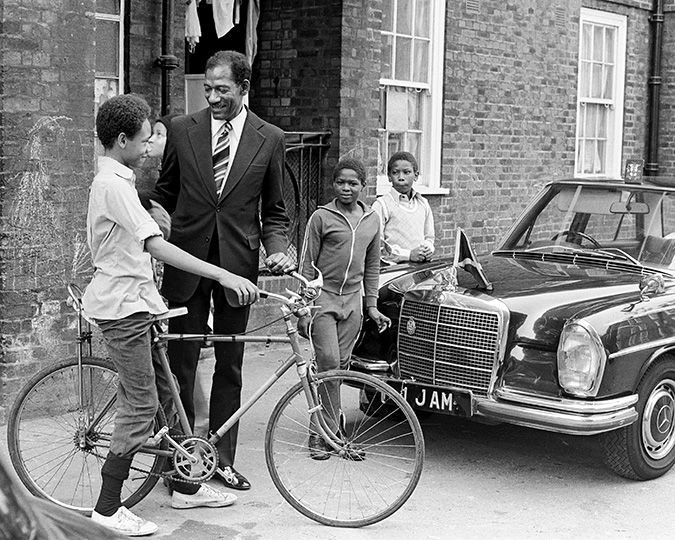

Julie Begum was born in Stepney and is chair of The Swadhinata Trust, a secular Bengali community group that works to promote Bengali history and heritage amongst young people. The first clothes Julie remembers wearing are 1970s style flares, turtlenecks and platform shoes. She describes standing out in secondary school as one of the few Asian or Black children and says there was ongoing tension and violence between people of different backgrounds.

Julie with friends at the wedding

© Delwar Hussain

A lack of South Asian dress shops influenced Julie’s choice of dress, along with her family’s open attitude to her wearing clothing of her choice. Although Julie is now an atheist, growing up in a Muslim family, the concept of modesty still has a big influence on the way she dresses.

Julie donates an outfit worn for a friend’s wedding, which combines traditional and non-traditional Bangladeshi dress, combining a salwar kameez with a vintage animal print coat.

Kia (third from left) with family members at Eid celebrations

© Peter Watson

“I

mean I have seven siblings so there's eight of us, and my nieces and nephews

ran out of different khalas, you know bawro khala, mezo khala, choto khala”

Kia Abdullah is an author and travel writer who now lives in the Yorkshire Dales. She grew up in Tower Hamlets with seven siblings. Her quote above describes how her nieces and nephews ran out of names to call their aunties as there were so many of them. In Bengali bawro khala is used for the oldest maternal aunt, mezo khala to the middle in age and choto khala to the youngest maternal aunt.

Kia donates a purple shalwar kameez worn for Eid celebrations, and a pair of jeans. Kia tells of the expectations to wear traditional clothing growing up, especially at her secondary school where the majority of students were Bengali and wore a shalwar kameez. Kia describes wearing jeans as a mark of her independence. Kia has always been strong-minded, knowing from a young age that she wanted to prioritise getting a good education and job ahead of marriage. Regardless of this, Kia loves to see her sisters in saris, and still wears traditional South Asian dress for special occasions. She has a great pride in the dress of her Bangladeshi culture, describing it as ‘beautiful,’ and enjoys having two cultures to draw inspiration from.

Mm, and in terms of Bengali culture, do you see that being expressed in...in your dress, or in...in the different, um, occasions that you might see or find yourself in?

A: Sure, yeah, so on Eid, you know, I'll be in salwar kameez, at weddings, engagements and so on, so formal events I'll always be wearing what, you know, what we would refer to as Asian clothes.

Q: Mm...

A: In my day to day basis probably not, you know, I just...I have a wardrobe full of Western clothes but I do love seeing all my sisters in sarees, you know, dressing up, and all...the six of us will always take pictures on Eid Day...

Q: Mm...

A: ...and, you know, the dress of our culture is so beautiful, you know...

Q: Mm...

A: ...it's so colourful...

Q: Yes...

A: ...the textures, and I'm really proud that that's part of my culture too. I'm really proud that I have these two cultures that I can tap into.

Q: Yes. Yeah. And there's a real celebration...

A: Absolutely...

Q: ...when it comes to these, um, particular days or events. There's, um, a shared sort of, um, celebration of that culture...

A: Yeah...

Q: ...in...in the dress...

A: ...and you almost...

Q: ...particularly for women.

A: Exactly, I was gonna say you almost feel sorry for men then because they're either in suits or they might wear a sherwani...

Q: [laughs]

A: ...but the women are the ones that look amazing.

Q: Yes, it's true actually. Yeah, I...I notice in the Boishakhi Mela how beautiful the girls and women are. I mean the men do look wonderful in their panjabis...

A: Mmhmm, mmhmm...

Q: ...as well but it's the women and girls that stand out...

A: Yeah, absolutely...

Q: ...you know, they are really decorative, you know, in their clothes and it's a very sort of, uh...uh, special moment really, to be on display in a way...

A: Yeah, yeah...

Q: ...that it's not really expected for...

A: For a man...

Q: ...boys or men in the same way...

A: Yeah...

Q: ...although they try and make up for it.

A: [laughs]

Sari worn by Baroness Manzila Uddin for her wedding ceremony

"I alongside, many other Bangladeshi women across the world, love wearing sharees, particularly Rajshahi Silk which originates from my birthplace. Sharees come in so many shades and hues which embody the rich colours and fabrics of women's lives. Sharees have a timeless elegance whether adorned by women working in the paddy fields or the boardroom. Most importantly, the six yard woven into a sharee symbolise the evergreen strengths, beauty and pride of being a Bengali woman."

Baroness Manzila Pola Uddin was born in Rajshahi, Bangladesh in 1959. In 1973, at the age of 13, she migrated to London with her mother and four siblings like many other families at that time, following the Bangladesh Liberation War and joined her father who had lived in London since early 1960’s.

Manzila was heartbroken having to leave her much loved and treasured extended family in Bangladesh particularly her aunt and grandfather who had been been intrinsically influential in her early childhood.

Having become a mother to two boys in 1980 she took up her post as a youth worker which heralded a longstanding passion commitment and career in community led activism. Whilst studying for her social work qualification in 1990 she became the first Bangladeshi woman to be elected as a councillor for Tower Hamlets Council. In 1998 she became a Member of House of Lords, being the first Bangladeshi and Muslim woman to sit in British Parliament.

Close-up of sari

Manzila has always been rooted in the communities of Tower Hamlets and has gifted her wedding sharee, bought from Modern Saree Centre, Brick Lane.

She was married in Bethnal Green at the age of sixteen and recalls it as a bitterly cold and snowy winter's day, with her feet absolutely frozen in her sparkly wedding sandals. Along the joy of her marriage she also experienced overwhelming feeling of loss, being alone for the first time, separated from family as her family did not approve of her marriage that time . However Manzila reconnected to her family soon after her marriage and family relationships are most significant in her life and in particular her mother who remains her greatest source of inspiration and support.

Manzila lives in Tower Hamlets and is blessed with five grandchildren and five children.

Lutfun recording her oral history interview

© Julie Begum

"It is my culture… I’m [at] work I’m wearing sari, and at home I’m wearing long dress, it’s comfortable and outside I’m always wearing sari."

Lutfun Hussain was born in Cumilla, Bangladesh before moving to Tower Hamlets in the winter of 1969. The year of her arrival was the first time Lutfun had seen snow, which she wrote home to tell her brother and mother about as she did not have access to a phone she could call them on. Lutfun’s family helped prepare her for the move, her brother buying her a jumper and her mother preparing a box of spices for her to bring with her. Lutfun found life very hard when she first arrived in London. She was often lonely, especially as there weren’t many other Bengali people in the area at the time, and describes crying often throughout the early months.

A traditional Bangladeshi boy's outfit bought by Lutfun for her grandson

Lutfun now runs the Coriander Club at Spitalfields City Farm, a gardening and cookery club founded in 2000 as a way for Bengali women to get together, socialise and grow the vegetables they would use in the cooking of traditional Bangladeshi dishes. Lutfun donates a traditional Bangladeshi boy’s outfit which she bought for her grandson.

"When it comes to clothes, if ask me about one outfit or one form of clothes that defines me, who I am, then that’s undoubtedly the sari. I look for opportunities to wear sari."

Leesa Gazi moved to London from Bangladesh in 1999. She has since worked in TV and theatre, co-founding the theatre and arts company Komola Collective, dedicated to telling stories which often go unheard from the perspective of women. Plays include ‘Indigo Giant’ a play based on the Indigo revolt, an 1859 uprising of Bengali farmers against exploitation and oppression by Indigo planters during the British Raj.

Leesa describes the sari as the one item of dress that defines her. She donates a red sari and range of jewellery items.

A: I love to wear bangles. And it doesn’t have to be gold or silver. It has to kind of call me.

Q: Yes. So why are bangles important for Bengali women as well as Sari?

A: Bangles signify so many things. I think that –

Q: Give an example.

A: Like you have to wear bangles if you are married is one thing. I mean, you have to like – even if it’s a very thin kind of Churi, which is a thinner bangle. You have to have that that’s the sign –

Q: The noise.

A: Yeah. The noise.

Q: The things on your hand. I have some distinct memories of going to Mellors in Bangladesh and buying some glass bangles.

A: Oh, my God. I love them.

Q: With my relatives. And just being so delighted by that activity. And we’d have an arm full of bangles.

A: Yeah, yes. And glass ones.

Q: Um, in particular.

A: Yeah. And the noise they do make. It’s just really [noise imitation].

Q: So as girls you do that?

A: Yes, yes.

Q: What else?

A: Oh, I should have brought tip that’s hugely, hugely me. I didn’t, but I will send you because –

Q: What is a tip?

A: A tip is a – it’s some stick-on –

Q: It’s a sticker you put on your forehead between your eyes.

A: Yeah, between – and it is – it actually signifies our culture as well. Like, I mean, a Bengali girl without Bindi – I wouldn’t say others. When I think of me, when I wear sari, when I wear a kind of [inaudible 0:53:40] kind of outfit, I have to have a tip.

Q: And some bangles.

A: And some bangles.

Q: And a sari.

A: And some earrings. And some [mullah 0:53:50]. I’m greedy, aren’t I?

Q: Yes, no. But that is normal, isn’t it, to have a necklace, some earrings, some bangles?

A: Yeah.

Q: And a sari with a tip.

A: And also, it doesn’t matter if it’s glass bangles or –

Q: No, the quality is not important.

A: It doesn’t matter. It’s just your heart’s desire, you just need to.

The items collected as part of ‘Weaving London’s Stories’ only just begin to scratch the surface of the huge diversity of experiences related to dress within British Bangladeshi communities in Tower Hamlets. A person’s relationship to dress takes into account a variety of factors, including tradition, practicality and the influence of fashion movements and trends. In this final oral history clip Aniqa and Anisha speak about the intersection between their culture and faith, as well as how the ways people relate to dress are constantly changing as attitudes and trends continue to evolve.

S2 That’s the thing with certain things that aren’t seen as….

S1 Acceptable within the community.

S2 Acceptable in the way of how you’re supposed to behave and do. You kind of have to hide it, in a sense.

S1 Yeah.

S2 So, it’s like, I know a lot of people that are from the area. They would do certain things, but because it’s not in their character, or like, when it comes to being Bengali—and it is heavily to do with gender, as well.

S1 Yeah.

S2 They’d have to go off somewhere and hide and do certain things because that’s a part of themselves, like, that isn’t part of their image here as a Bengali person. Especially with Muslims as well. Because if you’re a Bengali and Muslim as well, there’s even more added pressure of what you’re supposed to be like.

S1 Yeah. I think I was looking at that a few days ago. I was thinking about how say, like, we’re Bengali, but then a lot of our traditions don’t actually follow up with the Muslim kind of thing.

S2 Yeah.

INT Whereas I think it depends, like, where you grow up. So, say, like, my parents would put more of enforcement onto the Islamic point of view. And I think a lot of our Bengali traditions—

S2 Whereas mine is more open.

S1 Yeah. The Bengali traditions are more based around—I think when you look at it, it’s more like Indian cultures. And, you know, like, the parties and certain things like that. And I think a lot of people are like—you know, when they follow that it’s like, it works. Kind of like religion and our kind of like background, it’s two different things.

S2 Own traditions, yeah.

S1 And I feel there’s a fine line, like, separating them because certain things won’t be accepted.

S2 And people pick and choose.

S1 Yeah. Certain things are unacceptable in our religion—

S2 That’s what it is.

S1 —that aren’t acceptable. Like, say even when you look at clothing. Like, say a sari. Like, the blouse, this bit of your stomach would show, and this, and—

S2 And that’s not allowed.

S1 So, it’s not acceptable in religion. Whereas—and, you know, in religion, you have to be covered.

S2 But it acceptable with our traditions, with….

S1 Yeah. So, I was kind of like, there’s a—there’s a very, you know—there’s like a balance and it’s kind of like hard to juggle both, isn’t it? You have to, like, kind of choose one that has to, like, become your main identity in a way. Yeah.