London’s East End has long been a centre for the manufacture of clothing and textiles. In the 1960s and ’70s, the trade was predominantly taken over by Bangladeshi Muslims. Many of those businesses started and thrived in homes just like that of Asma Begum’s. Here’s the story of how her parents travelled from Bangladesh and built a life in the East End.

My parents were first-generation Bangladeshi migrants who settled in the East End in the 1960s and ’70s. Both of them worked in the East End ‘rag trade’ in leather garments. My father was a machinist and my mother worked from home as a seamstress.

Their story is an integral part of London’s story, and representative of the many British-Bangladeshis who made London their home, with humble beginnings in the rag trade. Many Bangladeshi women in the 1970s and ’80s used to work from home, while raising their families. Their toiling was unseen though clearly heard as the continuous drone of sewing machines formed an integral part of the East End’s soundscape. I grew up in one such household.

But, first, let me introduce my parents.

My mother Anwara Begum was born on 3 June 1954 in Sylhet (now in Bangladesh), as the sixth child to Mojumdar Ali and Lotifa Khatun of Sreeramshi village. Anwara married my father, Ashab Uddin, on 4 June 1972 in Bangladesh at age 18. On 16 May 1975, Anwara and her first child, Amina, joined my father in the UK.

My father Ashab Uddin was born in 1945 in Sylhet (now in Bangladesh). He was the seventh child of Asrab Ali and Kudaja Khanom of Kochrakali Village. His early years were spent in the hardships that followed the Bengal Famine of 1943 and the Second World War.

Orphaned at age seven, he was raised by his elder brothers. He studied diligently, and as a young adult, Ashab strived to better his life despite adversity. He went on to teach at a small village school in East Pakistan (now Bangladesh) in 1962. Times were hard and good jobs were scarce. Looking for other avenues, Ashab applied for a ‘work voucher’ under the Commonwealth Immigrants Act, 1962, and migrated to the UK the same year.

Ashab Uddin (centre) in 62nd Precinct, Kensington High Street, 1970. (Courtesy Asma Begum)

In 1967, Ashab Uddin was working for a leather factory run by Jewish employers on Princelet Street. He worked as a machinist for most of his adult life. On 8 March 1978, he took out a lease to start up his own leather factory — ‘Chicago Suede and Leatherwear’ — on Heneage Street, E1. Ashab then opened a unit in Kensington High Street called ‘62nd Precinct’, where he sold his many creations and leather garments.

In 1972, Ashab married Anwara. Three years later, when Anwara moved to the UK with their eldest child, the trio moved to a house on Quaker Street, off Brick Lane, the heart of the leather garment industry at the time. They had three more children and stayed there until 1996. I am the youngest.

Building a home and business in the East End

For over 250 years, Spitalfields and its surrounding areas have been a centre for the production of clothing and textiles. This started with the French Huguenots weavers, followed by a large number of Jewish settlers in the 19th century, who worked across the board in the textile/clothing business and owned factories. Eventually, the clothing trade was taken over by Bangladeshi Muslims, who continue on to this day. Many of those businesses started and thrived in homes just like mine.

Growing up, I remember my parents’ bedroom housed a clunky, industrial sewing machine in the corner. The machine was imposing and a stark contrast to the rest of the furnishings, like the frilly pillowcases and pleated valance sheets. But, somehow, my mother made it work in the Feng Shui of bedroom-y things. The room also had various sewing paraphernalia on the shelves. All around were spools of thread, decorative biscuit tins containing haberdashery, miscellaneous items and a greasy WD-40 can.

My childhood escapades of growing up in the 1980s consisted of predicaments such as being waist-deep in wool wadding, being disappointed at biscuit tins containing sewing stuff, being scolded for using the fabric scissors for my school projects, and going to school with a trail of thread attached to my clothes. I used to prop myself on the black bin bags of wadding as if it were a bean bag, play thread figures with yarn and watch my mother sew dexterously hours after hours as she listened and sang to Bengali songs. If mum wasn’t sewing for work, she was sewing as a pastime.

Anwara Begum, with the author, sitting next to her sewing machine at their home in 1982. (Courtesy: Asma Begum)

In 1984, my mother underwent an open-heart surgery and developed a chronic heart condition. Undeterred, Anwara Begum did not delay getting back to work to help bring in a household income. She was resilient in the face of adversity, passionate and formidable.

All this had cultivated within me immense admiration for the skill of sewing and for the machine that bought in a livelihood. Today, the Shoreditch area — though vastly gentrified — still has remnants of old factory buildings and textile shops dotted amid the myriad of Bengali-Indian curry houses. Echoes of times past. Even after the end of the rag trade in the late 20th century and closure of garment factories, many Bangladeshi households like mine hold on to our industrial sewing machines for sentimental value.

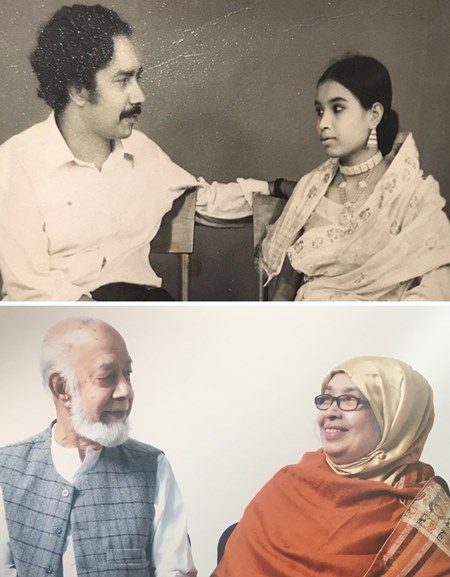

Ashab Uddin and Anwara Begum, just after their wedding, 1970s (top), and together in 2016. (Courtesy: Asma Begum)

Honouring the legacy

Unfortunately, both my parents passed within weeks of each other in the autumn of 2018. Having grown up seeing both parents sew, I felt I needed to pay homage for the dexterous skill that has intrinsically become a fibre of my being (pun intended). I grew up enjoying sewing over the years — from a hobby to delivering classes during the COVID-19 pandemic. Maybe, it was also subconsciously my way of connecting and giving back to my parents, and continuing their legacy. So, when I was honoured with an award for my contribution to the local community in Tower Hamlets, the recognition was sweeter.

The most emotional process after mum and dad passed was going through their belongings. I cried silently over mum’s beautiful saris, still immaculately folded, and after I found dad’s spectacles. Over the months, I sifted through an array of things, but one thing that was glaring at me was the family’s sewing machine. Idle and quiet, but one glance and there was a flood of fond memories. It was our family heirloom.

The Brother sewing machine

In the months preceding her death, my mum had told my siblings and I, to never dispose of the Brother sewing machine. My brother once referred to it as the Holy Grail and said that it must be preserved.

In 2018-2020, I got involved in a community-led book project exploring the untold stories of Bangladeshi seamstresses in London’s East End. We interviewed several Bangladeshi women in their 60s and documented their oral histories. Sadly, my mother had passed away so I gave a presentation of my first-hand observations as the daughter of a seamstress, growing up in the rag trade. In February 2020, our family’s sewing machine and I featured in the well-acclaimed BBC4 documentary, A Very British History: British Bangladeshis (Season 2, Episode 3). I was overjoyed as my parents would have been so proud to see their sewing machine appear on TV.

Subsequently, I donated the sewing machine to the Museum of London to showcase the achievements of Bangladeshi migrant diaspora who contributed to London’s history. What better way to carry on the legacies of Anwara Begum and Ashad Uddin than by sharing not only their story, but that of the Bangladeshi community in the East End garment trade with generations to come.

London-based Asma Begum is the daughter of Anwara Begum and Ashab Uddin, mother to four children, a writer and sewing enthusiast.

Anwara Begum’s story and her Brother sewing machine form an important part of the Museum of London’s exhibition ‘Fashion City: How Jewish Londoners shaped global style’ until 7 July 2024. You can also buy our book that accompanies this major exhibition from our online shop, and at a discount when bought alongside your exhibition ticket.

Subscribe to our fashion newsletter to read more stories from our collection, and see upcoming events and exhibitions.