The East End has a long association with immigration, offering a first home to many new arrivals to London. From the end of the 19th century the settlement of thousands of Jewish families fleeing persecution in east Europe transformed Whitechapel and Spitalfields into a cosmopolitan, vibrant district where Yiddish could be heard on every street.

Between 1880 and 1914, London’s small Jewish community was transformed by the arrival, into the UK, of 150,000 East European and Russian Jewish refugees. Fleeing economic hardship and religious persecution, up to 70% of the new immigrants settled in London’s East End swelling an already well-established Jewish neighbourhood concentrated in the area between Spitalfields and Whitechapel.

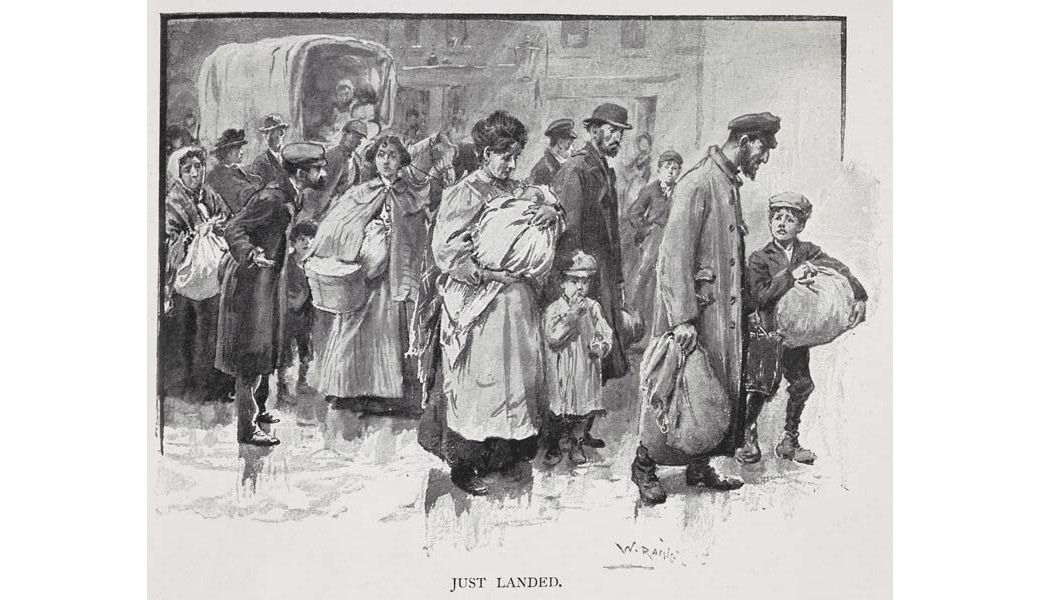

Jews coming in to London, 1902-1903

An illustration from ‘Sweated London’ by George Sims, an essay on the experiences of immigrant Jews when they land in London. (ID no.: LIB5332/MH2)

This district of London had long been associated with immigration primarily due to its proximity to the docks and Liverpool Street railway station, the point of disembarkation for those entering the capital via the port of Harwich. Arriving with little apart from the name of a relative or friend with whom they could find temporary shelter, the new immigrants were encouraged to settle in the area due to the availability of cheap housing, cultural and social networks, and plentiful work opportunities.

Where did Jewish people initially settle in London?

The impact of mass Jewish immigration on an already overcrowded East End raised some concerns amongst the authorities as well as the established Anglo-Jewish community and overstretched charity workers. To outsiders, the Jewish East End seemed an alien ghetto populated by “strange exotics”. Their unfamiliar language, diet and religion could raise suspicion and crimes that appeared to be “foreign to the English style”, including the Jack the Ripper murders, were often falsely blamed on the new arrivals.

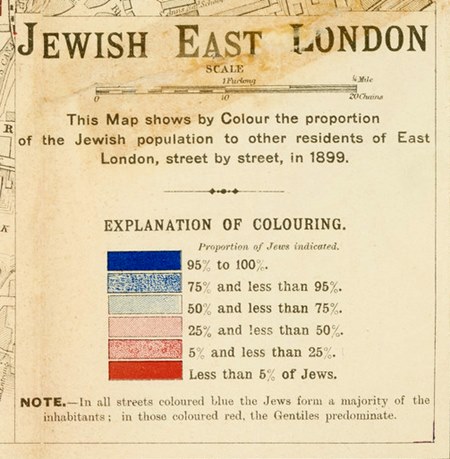

It was against this growing climate of concern that George Arkell was, in 1899, commissioned to create a map illustrating the spatial distribution of the growing Jewish community in the Spitalfields and Whitechapel area. The map was published in The Jew in London: a study of racial character and present-day conditions, alongside essays by Cyril Russell and Harry Samuel Lewis that aimed to “describe the Jewish community in London”, and assess the social and economic impact of the new arrivals on the capital. Arkell adapted the method of colour coding used in Charles Booth’s 1889 Descriptive Map of London Poverty to identify levels of poverty to illustrate, in this case, the density of Jewish residency in each street.

'The Jew in London'

The colour key to George Arkell’s 1899 map, with blue representing highest density of Jewish population, and red, the least. (ID no.: LIB26770)

Jewish families were identified by their names, their schools and the observance of Jewish holidays. However, the Jewish East End was not a segregated ‘ghetto’, and Jews and non-Jews lived side by side. Christian children known as ‘Shabas goy’ would be employed to light fires in Jewish homes on the Sabbath and many non-Jewish women were employed as cleaners and took in washing for their wealthier Jewish neighbours.

In his introduction to The Jew in London, Samuel Barnett expresses the hope that the publication will “do away with the prejudices which are founded either on the selfishness which is jealousy of the Jews’ success or on the ignorance which is irritated at their different habits and opinions” and “dissuade any attempt to check by law the entry into England”. Just five years later, however, the government passed the UK’s first immigration act.

The Aliens Act of 1905 aimed to restrict immigration solely to refugees fleeing religious or political persecution. It was also meant to allay fears of the existing population that Jewish immigrants were taking jobs from locals and keeping wages low whilst pushing up rents in the area. But while anti-Jewish sentiment could flare up in street fights and also found an official voice in the anti-alien pressure group British Brothers League, established in 1901, anti-Semitism was not a mass movement within the East End at the turn of the 20th century. Most non-Jews living in the East End within the area accepted the ways of their immigrant neighbours.

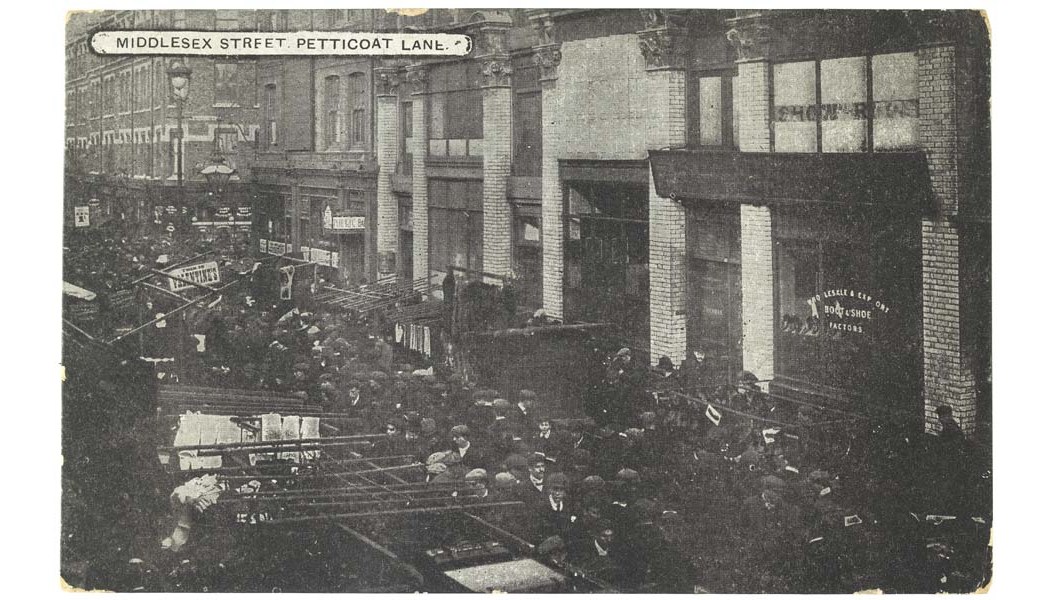

The Jewish East End was a vibrant, self-contained neighbourhood. Throughout the working week community life focused on Wentworth Street or ‘The Lane’, which resounded with the sounds and activity of Yiddish-speaking traders. On Saturday evenings, social activity transferred to the wide pavements of the Whitechapel Road as Jewish families celebrated the close of the Sabbath by partaking of ‘The Saturday Walk’. Although Polish, Russian and Eastern European Jews were culturally diverse the Yiddish language was a common bond uniting all new arrivals.

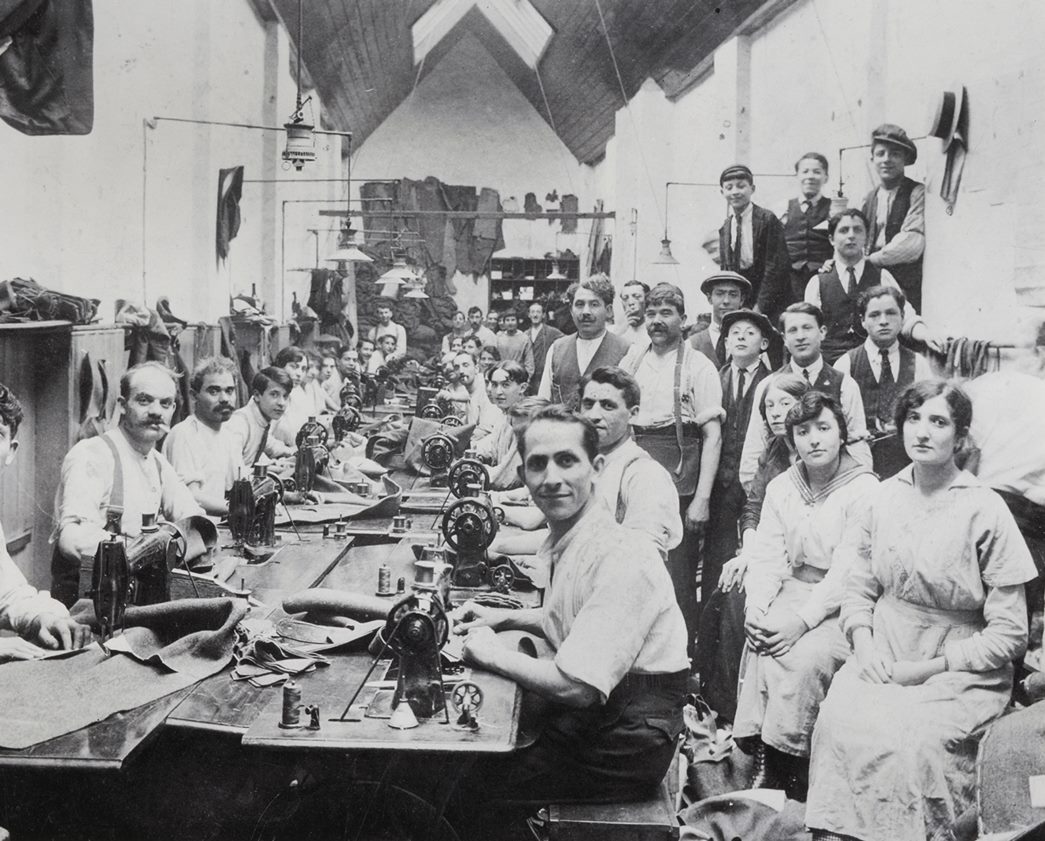

Jewish tailors in London

Many Jewish immigrants found local employment in the clothing industry which, by the 1880s, was dominated by the ‘sweating’ system of small workshops and the subdivision of labour into unskilled or semiskilled tasks. In 1889, Charles Booth’s researchers counted 571 workshops making men’s coats in less than one square mile in and around Whitechapel. Most employed fewer than 10 workers confined for long hours in cramped, damp and steamy workrooms, an ideal breeding ground for tuberculosis.

Whilst the clothing trade dominated the Jewish East End employing up to 70% of its workforce, others found employment as local market traders and shopkeepers providing the services essential for maintaining the Jewish way of life. Jewish grocery stores, bagel bakeries and kosher restaurants thrived and by 1901 there were 15 kosher butchers in Wentworth Street.

The immigrants maintained religious traditions by attending small, self-administered synagogues based on the old village communities of

Education was regarded as a means to economic and social advancement and most Jewish parents applied to send their children to the voluntary aided Jews’ Free School in Bell Lane which, by 1900, had over 4,000 pupils and was the largest school in

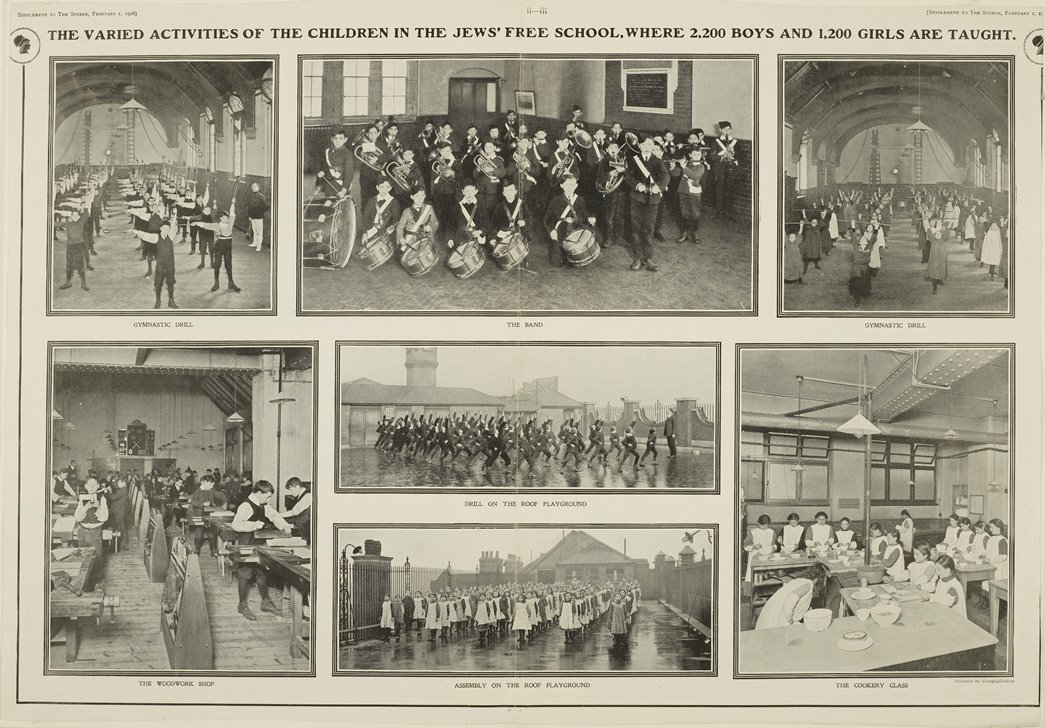

The varied activities of the children in the Jews' Free School

Images from an article in The Sphere magazine, 1 February 1908. It describes the work of the Jews' Free School in Spitalfields. (ID no.: 2006.79/25)

Creating a supportive Jewish community in London

The established Anglo-Jewish population supported the new arrivals through charitable assistance and advice. Jewish immigrants received help from a large network of relief agencies, including the Jewish Board of Guardians, which gave loans for the purchase of sewing machines, and the Poor Jews’ Temporary Shelter on Leman Street, which offered board and lodging for the first two weeks of arrival.

A young Anglo-Jewish couple on a Jewish New Year greetings card, 1891-1910. (ID no.: IN4925)

Wealthy Anglo-Jewish families, including the Rothschilds, also supported the building of affordable living accommodation for skilled Jewish workers. The first tenement block built primarily for Jewish immigrants, the Charlotte de Rothschild Dwellings, opened in 1887 in Flower and Dean Street. A second estate soon opened in Brady Street and the Nathaniel Dwellings, accommodating up to 800 Jewish workers, were completed in 1892. There was a strong sense of community within the Rothschild buildings. Many had young families and by the 1890s there was a birth in the Buildings every nine or ten days.

The arrival of the Jewish immigrants transformed Whitechapel and Spitalfields into a cosmopolitan, vibrant district filled with extended families. Despite high levels of poverty, many who grew up in the Jewish East End, such as artist Mark Gertler, comedian Bud Flanagan, diamond merchant Berney Barnato and writer Israel Zangwill found the area also provided inspiration for success in later life. Although many immigrants arrived penniless, their hard work and drive to improve their lives ensured that the East End Jewish population was socially more upwardly mobile than the surrounding non-Jewish population.

This is an edited excerpt of the essay ‘The Jewish East London, 1899’ published by Old House Books in 2012.

To find out more on how Jewish Londoners shaped global style, book your tickets to our latest exhibition ‘Fashion City’ here. The exhibition will run at the Museum of London Docklands from 13 October 2023 to 7 July 2024. You can also buy our book that accompanies this major exhibition from our online shop, and at a discount when bought alongside your exhibition ticket.

Love history and trivia? Subscribe to our free History of London newsletter for stories from our collections, displays and exhibitions.