What can fragments of a 19th-century child’s mug tell us about British sign language? A lot! While sign language or fingerspelling has been around for centuries, the 19th and 20th centuries were very significant for its development and acceptance, despite an extended ban. We find out more from these unusual fragments in our collection.

The Museum of London collects archaeological material excavated from all around Greater London. The Archaeological Archive collection includes over 9,000 site archives dates between 1928 and today, among which sit three intriguing fragments from a creamware children’s mug, produced between 1820 and 1840.

While such creamware pots and mugs aren’t uncommon in London homes or even at the museum, what makes these three fascinating is a pattern of fingerspelling or an earlier version of British Sign Language (BSL) printed in clear blue! This indicates that there was a fair bit of interest and market for BSL crockery as far back as the early 19th century!

An unusual find!

The fragments were found in a small excavation in St Stephen's Road, Bow, in 1975 by the Inner London Archaeological Unit. Interestingly, the Museum of London has the world’s largest archaeological collection, with hundreds of thousands of ceramic objects (many with names, lettering and pictures) — but we’ve found only three such tiny fragments with prints of sign language, that too from the 1820s–40s, among them!

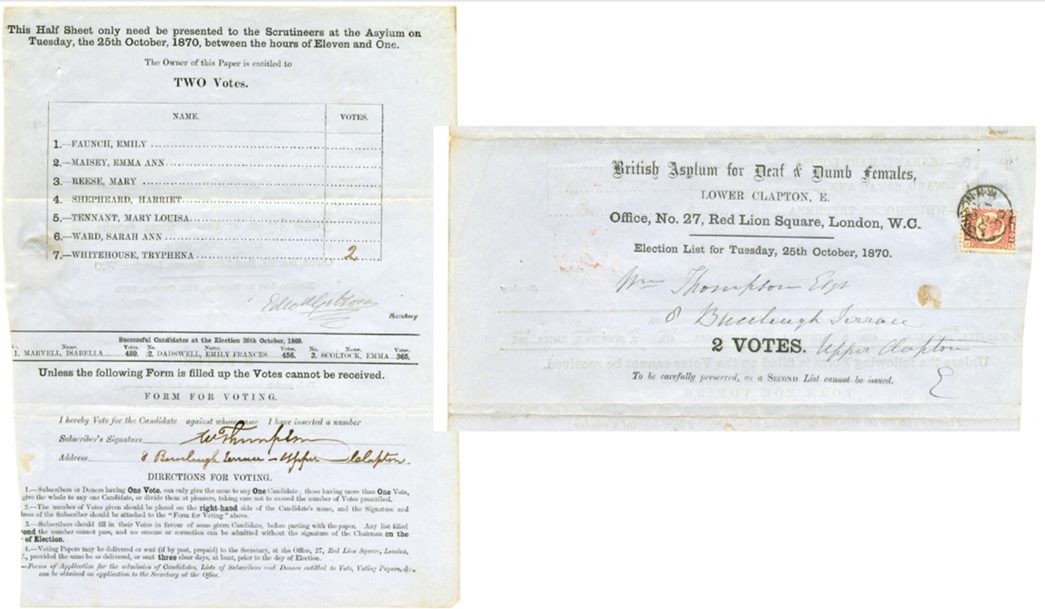

A leaflet with a drawing showing Queen Victoria using sign language at the bedside of a 'deaf mute'. (ID no.: 82.718/7)

Thereon began the research to find out the history behind these fragments. Some online instances of similar fully intact mugs were found in museums, private collections and auction houses. However, those examples were few. The fact that the little mug in the museum’s collection does not have a maker stamp means that we don’t know exactly where it was produced. However, since white earthenware with blue glaze was somewhat of a Staffordshire speciality, says Curator of Making Danielle Thom, it would be safe to suggest it was made in Staffordshire, one of England’s biggest pottery regions at the time.

Not just a child’s play

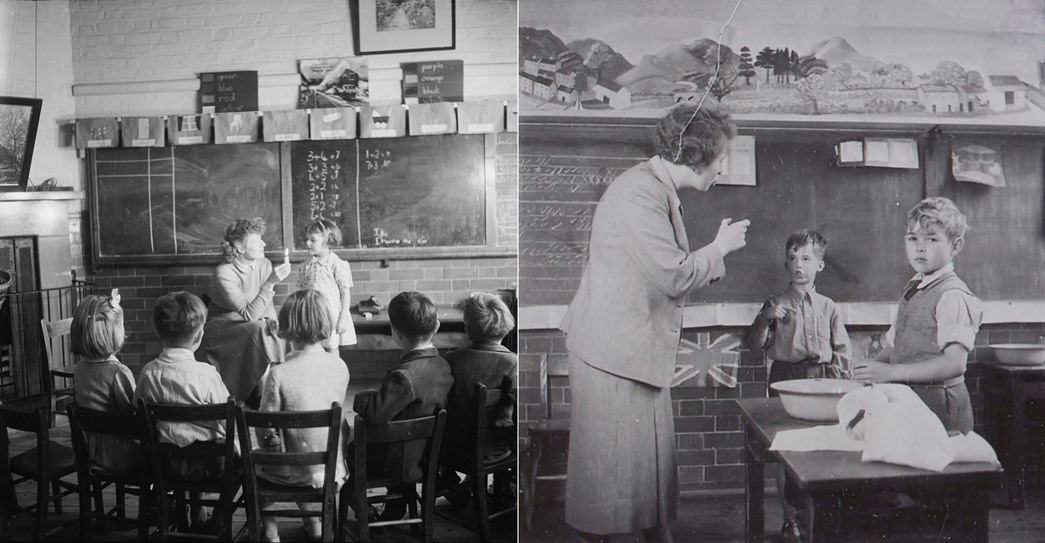

The mug’s size and subject indicate that it was meant for children. Called ‘children’s ware’ in museum-speak, such mugs and plates were quite popular during the 18th and 19th centuries, especially as presents. While wealthier children were given Chinese porcelain or silver mugs, most children would receive similar decorated ceramic plates and mugs. Some adults might have even kept them as collection/decorative items.

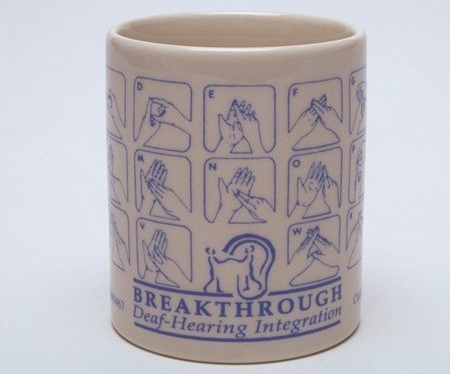

A ceramic drinking mug transfer-printed with the fingerspelling alphabet. (ID no.: 2000.178)

We find some of the earliest examples of such nursery ware from the early 19th century. Designs included depicting children playing, in household settings, country life, etc., some with short quotes and poems, and others with alphabets. The fingerspelling mugs — while much fewer in production — would fall in the last category. According to mudlarker Richard Hemery, who has seen fellow mudlarkers come across similar sherds as those in the Museum of London’s collection, “there are two transfers used on mugs around the 1830s–40s, with two colours of transfer (blue, black) and two different handle shapes. This implies there was a substantial output… I think they should not be regarded as mass produced, just one of the many sidelines made by factories”.

A transfer-printed china teacup and saucer, part of a doll's tea service (1908-1912). (ID no.: 65.74/53)

Thom explains further: “The nature of transfer-printing means that it doesn’t make sense to only produce a small number of something, because you have to prepare an engraved metal plate with your design, which is then inked, transferred onto a flexible ‘bat’ (usually some kind of rubber), and then the inky bat is transferred in turn onto the surface of the ceramic. The preparatory work was sufficiently labour-intensive that it was only justified by using the metal plate multiple times.”

Thus, while it seems that such mugs were not rare, they were definitely unusual. The non-existence of makers’ marks and lack of proper documentation — even the printing plates — on these creamware make it difficult to gauge their circulation. Though a fingerspelling Staffordshire mug is known to be part of a museum in the US, suggesting that people travelled with them.

A place in history

What makes finding these mugs even more significant is that around 50 years later, the 1880 Second International Congress on Education of the Deaf, in Milan, infamously passed several resolutions declaring that sign language was inferior to oralism, and ought to be banned! (Of all the delegates, only one was deaf.) While this led to a noticeable shift in deaf schools across the world, according to Thom, the existence of sign language plates and mugs from the late 19th century suggests that there was still some market for these wares in Britain. Some bearing the mark of the famous “H. Aynsley & Co (Ltd)”, but those are closer to the 1900s and thereafter.

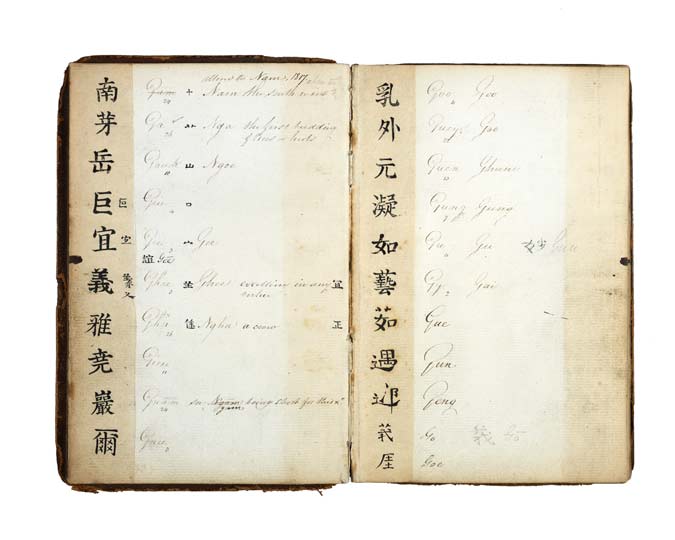

When one looks at the history of the British Sign Language, it has been found that different versions existed since almost the 7th century. However, one of the earliest known records dates back to a 16th century marriage registry. Another well-known reference is in Samuel Pepys’ diary, where he writes that a young deaf boy “made strange signs of the fire” to describe the Great Fire of London to his friend Sir Georgie Downing and himself. He wrote:

But, above all, there comes in the dumb boy that I knew in Oliver's time, who is mightily acquainted here, and with Downing; and he made strange signs of the fire, and how the King was abroad, and many things they understood, but I could not, which I wondering at, and discoursing with Downing about it, "Why," says he, "it is only a little use, and you will understand him, and make him understand you with as much ease as may be."

It took around 30 years more for the foundation of BSL as we know it now to be laid. And it wasn’t until late 18th century that Thomas Braidwood opened the first formal schools for deaf children in Edinburgh and London. However, these schools were private. General access to a deaf school had to wait until 1792, with the opening of the London Asylum for the Deaf and Dumb in Bermondsey.

Coinciding with the industrial revolution, a growth in population meant a rise in the community of people with hearing and speech impairments community as well. The original mug — of which the museum now holds the sherds — with the glazed print of a version of BSL would have been made around this time. Hemery is “certain they would have been bought by schools and institutions, to be used in a practical way, and as rewards to give children”.

The case of the unusual mug

So whom did our mug belong to? We do not know. It could have been given to a child as a reward or gift, or part of a ceramic collector’s collection. Maybe it was used every day, or maybe it was kept on a shelf to symbolise something dear to the owner. We cannot know for sure.

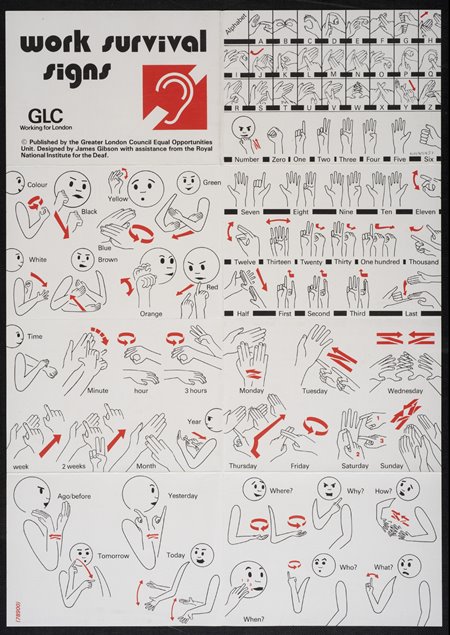

A poster printed with work survival signs. (ID no.: NN40437)

What we do know, is that it’s an important but little explored part of British Sign Language history. And as such examples stand along with a shelf full of alphabet-ware ceramics, it represents crucial steps in the path to recognition, inclusion and education.

It took around 90 years after the 1880 ban to fingerspelling,

for sign language to be reintegrated in schools. And it was only in 2003 that

the BSL was recognised by the British government. After members of Parliament backed the BSL Bill in its third reading in March 2022, it is finally set to get legal

protection, giving a sense of official acceptance to a language signed by at

least 87,000 deaf BSL users in the

UK.

The three sherds of presumably a child’s mug carry behind their blue glazed print, a story of hope, future, inclusivity and positivity among London’s strong deaf community.