Looking through the Museum of London’s collection is an opportunity to discover and share surprising stories that sometimes connect seemingly unrelated items. Three such objects are a seemingly sinister Valentine’s Day card, a man pictured on a polka dot pony and a Georgian garter advert.

There are over 1,700 Valentine’s cards in the Museum of London collection. Most were donated by Jonathan King, an Islington-based stationer who ran a card making studio. The cards tend to be beautifully decorated and propose generic romantic gestures that would not seem out of place in valentine’s messages today. Others have not dated so well, unless you find the invitation to go and do your lover’s washing and ironing an attractive one.

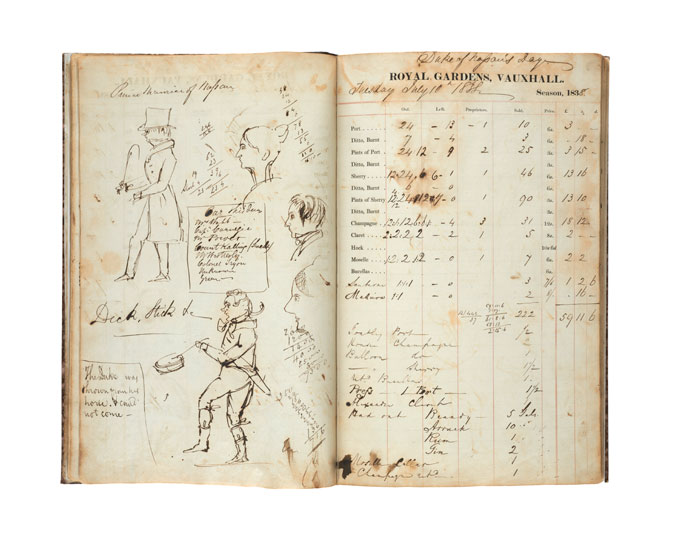

One particular card stands out as so strange and sinister that through the eyes of a modern audience it is hard to comprehend the motivation behind it. Within an embossed border, the illustration has a caption handwritten in blue ink: ‘My late dear wife preserved in a glass case. She was such a darling pet that I had her stuffed. Will you be my second?’. The central image depicts a bell jar containing a woman with flushed cheeks and a grin, presumably the preserved body of wife number one.

Valentine’s Day card

Valentine’s Day card with cream lace border, 1825-1850. 34.170/390

Just like internet memes today evolve to tell stories of current events, this Valentine’s card likely reflects a contemporary tale. The card dates from around 1825, so to better understand how such a card could be given as a token of affection it is worth taking into consideration popular gossip from the time. The reference on this card could well be explained by a series of events involving an eccentric dentist, Martin Van Butchell, and his first wife.

Sadly, as with the written records of many women in history, there is very little information remaining about the first wife of Martin Van Butchell. The majority of information left from the time is about him, she is often merely mentioned in passing as his first wife. She is sometimes referred to as Mary, and other times Maria in written sources. It may be that the name Maria was anglicised to Mary, which could explain these discrepancies. In Martin’s own records he refers to her as ‘my wife’. It is not unusual to have so little information about a seemingly prominent individual’s wife. Women had very few rights at the time and when a woman married she legally became united with her husband and what was hers became his.

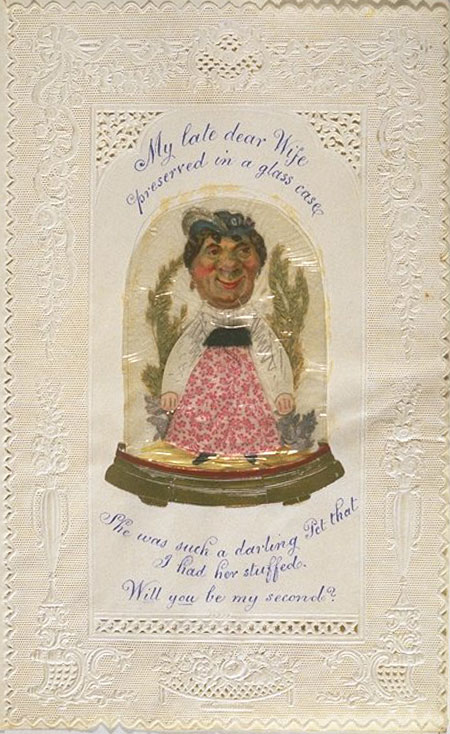

‘The Famous Mr Martin van Butchell’

Acquatint depicting ‘The Famous Mr Martin van Butchell’ on a horse, 1759-1775. NN27767

On January 14, 1775, Martin’s first wife died of natural causes at the age of 36. Her husband had trained under John and William Hunter, brothers who were prominent surgeons and enthusiastic anatomists. It’s not recorded why Martin wanted to preserve the body of his wife, whether it was because he could not bear to be without her, or if a clause in their marriage settlement gave him more control over property while his wife remained ‘above the ground’. A reassuring epitaph in newspapers at the time suggests the more romantic former of the two. Regardless of the reason, or if she had agreed to the process, less than 12 hours after her death, her body started to undergo embalming. Her preservation was carried out over the next few days by William Hunter, William Cruikshanks and Martin himself.

Preserving and displaying the body of one’s first wife in the home was not normal practice in Georgian London and would certainly have been the talk of the town. We know that Martin had to post a notice to reduce the number of visitors to his house to view his wife’s remains.

His decision to display his embalmed wife wasn’t the only unusual aspect of Martin van Butchell’s life. In the Museum of London’s collection there is also a black and white printed illustration of Martin on a pony. It doesn’t look too unusual until you learn that his pony was often painted with purple spots, black stripes, or occasionally completely purple.

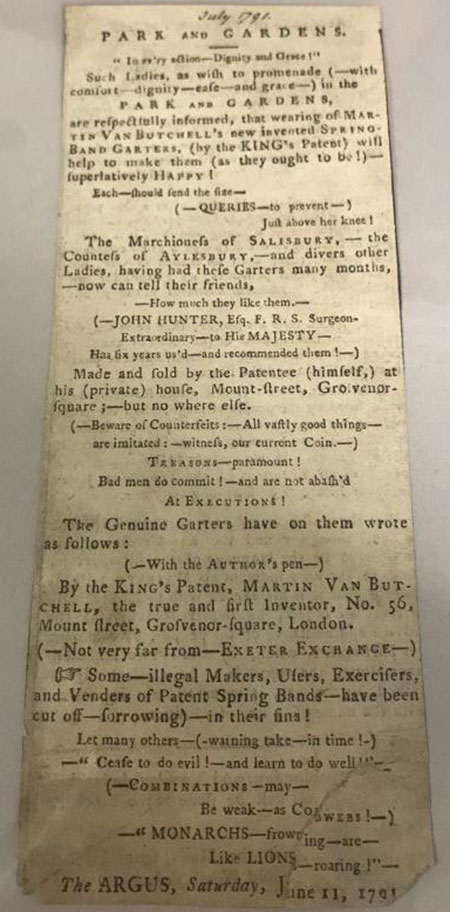

Newspaper cutting

Newspaper cutting advertising Martin van Butchell's 'new invented spring-band garters (by the King’s patent)', 1791. NN36380

Martin, for all his idiosyncrasies, appears to have been a respected dentist during his life. His fees were high and unusually for the time he refused to go to house calls, once turning down a massive 1,000 guineas to visit a patient at home. He also had a sideline selling trusses and garters for men and women, for which an advertisement exists in the museum’s collection. In fact, the advert implies that these garters were so sought after that fakes were made to replicate them.

Martin died on October 30, 1814 at the age of 80. In the year after his death his first wife’s remains were offered to the Board of Curators of the Royal College of Surgeons by Martin’s son. Her preserved body was put on display in the Hunterian Museum in London, - a practice that would have different ethical and legal implications today - and her unusual story was still in living memory at the time that this Valentine’s card was produced. Sadly, her embalming did not age well. A visitor in 1857 recorded her remains as ‘shrunken’ and ‘hideous’, but with a ‘remarkably fine set of teeth’. It is probable that she would have stayed there if it had not been for a fire caused by a bombing raid in May 1941 that destroyed her remains together with a large part of the museum’s collection.

Although we can’t be certain that this Valentine’s card is referring to these specific events, it certainly seems to mirror the unique story surrounding an eccentric purple-spotted-pony-riding dentist and his wife who lived in Georgian London.