One of the earliest known international coverage of the Great Fire of London disaster is a 1666 report from Valencia, Spain. Given the anti-Catholic prejudice in London at the time, this account tells the story of the fire from a Catholic viewpoint. Find out more about this fascinating document.

“…let those who have escaped from this punishment with their lives give their thanks to God; and (having recognised the true Roman Catholic Church) let them pray to God that he may spare them from a greater fire, namely, the fire of Hell.” (Relación nueva y verdadera del formidable incendio que ha sucedido […] en la ciudad de Londres. Valencia, 1666. Translated by J.K. Kennedy, 1923)

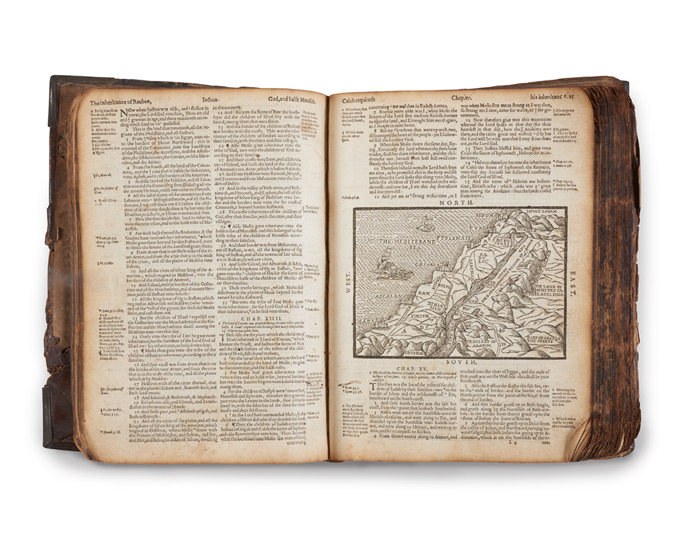

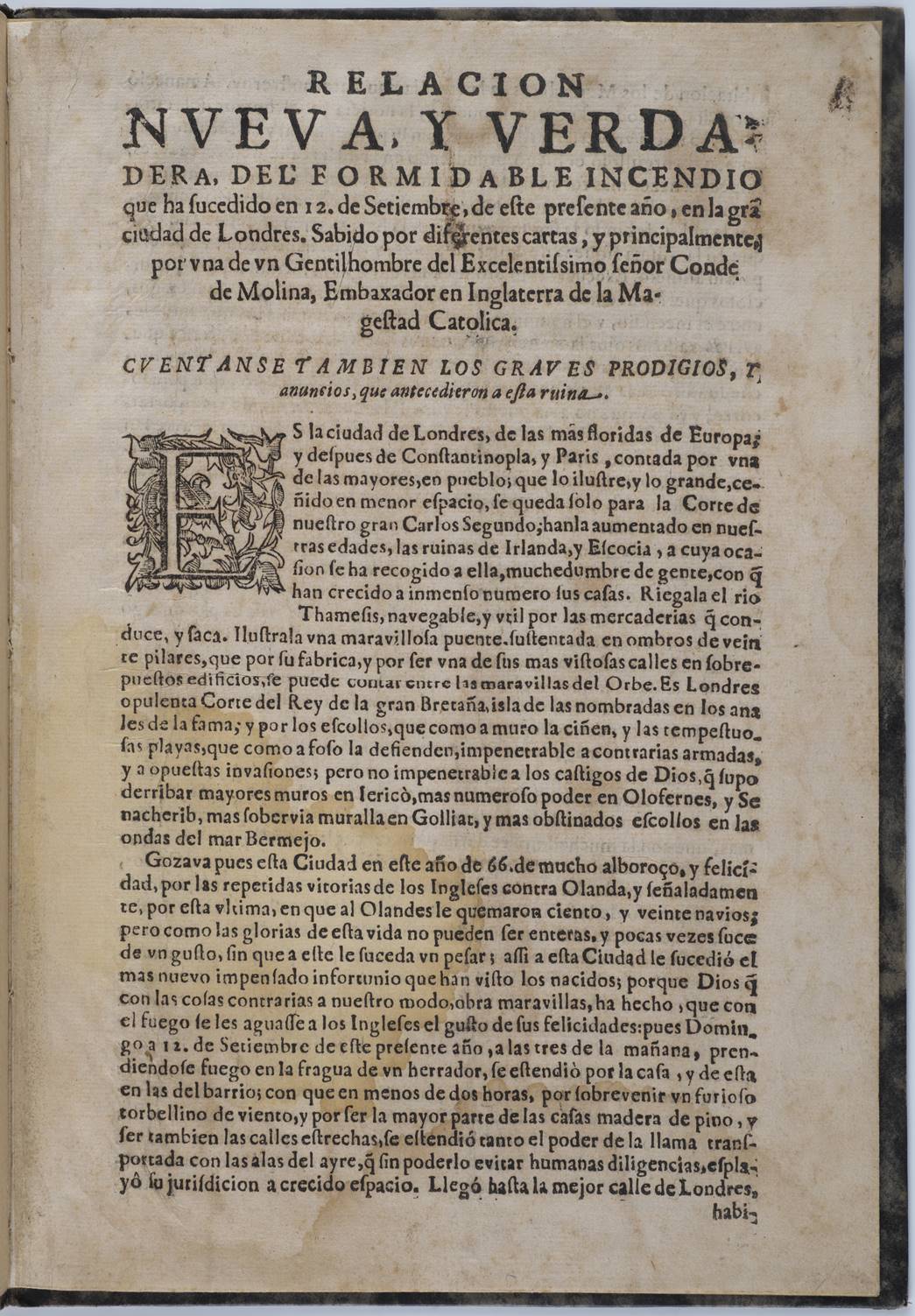

The news of the destruction caused by the Great Fire of London in 1666 spread like the fire itself across the country. But how was the incident reported abroad? One of the earliest international coverage of the incident is a 1666 report in the Museum of London’s Library — titled ‘New and true account of the formidable fire that occurred…in the great city of London’ — published in Valencia, Spain. While the title claims to be a ‘true account’, the pamphlet has some historical errors. However, it remains an important document that shows religious and political influences in international coverage from 1666.

Interestingly, given the anti-Catholic prejudice in London at the time, this account tells the story of the fire from a Catholic viewpoint (Spain being a Catholic country), informs curator Meriel Jeater. It says the fire was a judgement from God on London as a Protestant city and in punishment for the killing of Catholic martyrs. The destruction of St Paul’s Cathedral was due to the saint’s anger that the ‘false religion’ (Protestantism) was being preached there.

Here’s part of a translation of the pamphlet published by Great Fire of London expert Walter George Bell: “No doubt the great Paul, not satisfied with the worship of the false religion which went in inside its walls [referring to St Paul’s Cathedral], preferred to see the magnificent edifice sacrificed to the fire rather than left for the veneration of a heretic cult.”

The text has historical, often biased, errors, but still gives an interesting insight into how the Spaniards saw the Londoners’ way of life, which was now threatened by the fire. The author, for example, writes about the loss suffered by both merchants and farmers, everyday activities in the city that were now affected, and recounts the presence of Charles II and his brother, the Duke of York during the fire. The pamphlet also includes mentions of the unusual firefighting systems that the city had in place.

Not impressed with the warning bells, the text had this to say: “The sound of the bells noisily warned the parishioners; but since these bells were not rung in Catholic churches, their only effect was to make a noise and not to act as a help.”

The front page of the four-page pamphlet giving an account of the Great Fire of London, published in Valencia, Spain, in 1666. Read the digitised pamphlet here. (5.07MB). (ID no.: 42.39/34)

Was the Great Fire predicted?

Another aspect of this pamphlet is how the text feeds into the supernatural, with accounts of events later seen as predicting the disaster. It mentions a pyramid of fire raised from the sea three times in three days, and also the birth of a monster in London, a horrible beast with “the colour partly fiery and partly yellow, on the chest a human face, the legs of an ox, the feet of a man, the tail of a wolf, the breasts of a goat, the shoulders of a camel, a long neck, and instead of a head a tumour with horse ears.” Horrible indeed. It is also said that during the clearance of the ruins of a Puritan church a Latin inscription was found. This read: “When these letters shall be read, woe on London, for they shall be read by the light of a fire.”

How did the Great Fire of London end?

The report exaggerates the final damage of the fire. It says 140 churches and 55,000 homes were destroyed, when, in reality, these were 87 churches and 13,200 homes. To further support the theory, the Spanish text refers to 8,000 fatalities. Though we do not have a confirmed death toll for the Great Fire, the available evidence suggests it was perhaps under 20 people.

The text also says that the fire was finally stopped at the Catholic chapel at the Queen's residence, Somerset House, on the Strand. This was taken by the Spaniards as a sign from God to demonstrate the true faith. In fact, the fire was halted at the Temple and never reached as far west as Somerset House.

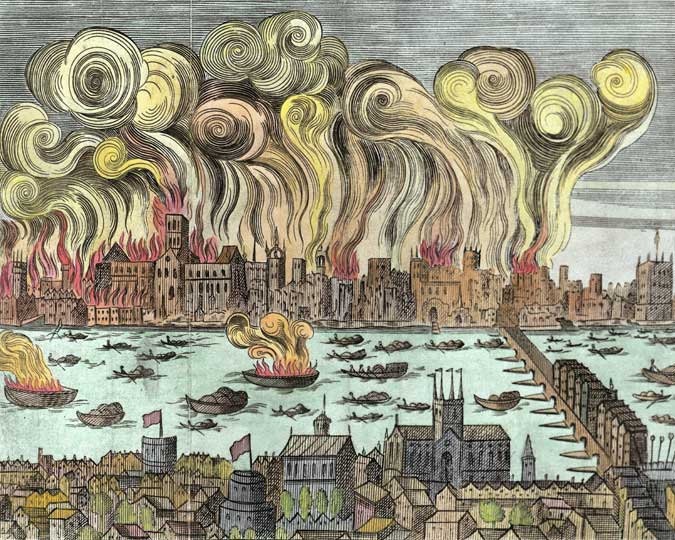

The Great Fire of London, c1666

Not signed. Taken from the West just beyond Essex Stairs. (ID no. 95.313)

Here is another section from the translation in Bell’s book: “It was observed that, in view of the direction in which the flames were extending, the first building on which they would have had to fasten, and the one nearest to them, was the Roman Catholic Church which was allowed for use of the Queen-Mother [Henrietta Maria] and her family and for the celebration of the holy sacrament. At this very point the onrush of flames was arrested: and it is very clear and certain that in this way the Almighty (who is Lord of all the elements) wished to rebuke the blindness of those heretics, and to show in what respect he held the sovereign Sacrament of the Altar. A hundred and forty churches of the heretics, including St Paul’s, and extending over thirteen principle parishes, were destroyed by the flames; but at the sight of a Catholic temple the fire acknowledged itself and was conquered.”

Many Londoners were originally unaware of the causes of the fire, and so looked at external enemies as possible culprits. “It seemed that suddenly, another building was on fire and it was, ‘Why did that happen?’ They didn’t necessarily think there was spark involved, or another natural cause… England was at war with France and the Netherlands, so it was perhaps natural to assume that there might have been some element of deliberate attack to it,” says Meriel Jeater. The Spanish pamphlet brings us the opposite point of view, that of Londoners from overseas eye-witnessing a destruction the scale of which they felt could only be explained by God’s wrath.

Read the digitised pamphlet reporting the Great Fire of London here (5.07MB). The translated text is from W.G. Bell’s book The Great Fire of London in 1666.

This pamphlet is part of the W.G. Bell Bequest in the Museum of London’s Library. The collection specialises in the Great Plague (1665) and the Great Fire (1666); it can be browsed here.

Header image: Engraving, printed in Frankfurt in 1670, by Matthaus Merian the Younger (1621-1687) of a view of London from Southwark during the Great Fire of 1666. (ID no.: A13757)

Love history and trivia? Subscribe to our free History of London newsletter for stories from our collections, displays and exhibitions.