As part of the Museum of London Curating London programme, funded by Arts Council England, staff from our curatorial and engagement teams are working together on London Eats.

Over the course of the year, the project aims to understand and reflect upon Londoners’ relationship with food and drink through new collecting.

We’ve started to consult community groups and school children to find out what food means to them. We’ve also looked at audience research commissioned over the past ten years, to understand people’s feelings towards food and drink. These insights and discussions will help inform the objects and stories we collect over the coming months.

We’re also researching in more detail food items in our collection. Which objects do we have, which stories they tell, and what is their relevance to Londoners today? Here we share some of these objects, and how they relate to the contemporary food issues we’re discussing with others.

Food justice, class and inequalities

What we eat can be an indicator of sharp inequalities. Even in a city of plenty, many still go hungry.

Fish porter's hat

‘Bobbin’ hard hats like this were worn by porters working in Billingsgate Wholesale fish market. Made from thick leather nailed together and finished with tar, the flat top meant they could balance cases of fish easily on their head, whilst the thick upturned rim is designed to catch escaping icy water, and any fish juices. Each hat weights up to 1.5kg and could survive 40 years of use.

Which clothing today is unique to London’s food traders?

Oysters

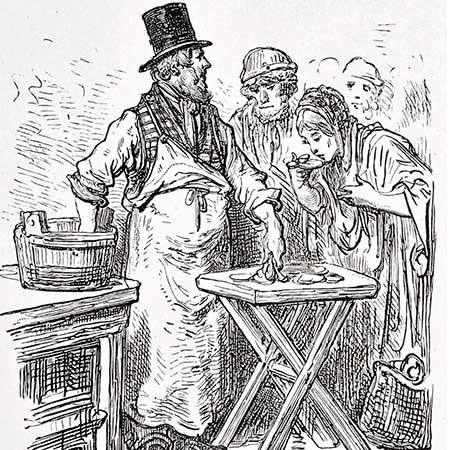

The Oysterman

A book illustration by Gustave Doré, 1872

While oysters today are on the menus of London’s finest restaurants, in previous centuries they were eaten by wealthy and poor people alike. In the medieval times for example, they were viewed as a medicinal food and given in quantity to London’s hospital inpatients. Back then oysters were so cheap and plentiful that they were the food stuff of the very poorest.

Which of our commonplace foods will be the elite foods of the future?

Loaf of bread

Loaf of bread

On display in our People’s City Gallery at Museum of London, London Wall

This small loaf of bread was given to a Suffragette serving a term of imprisonment for militant action in Holloway Prison. She kept it, uneaten, as a souvenir. Many of the 1,000 Suffragettes who went to prison in their struggle for the right to vote refused to eat, and often drink, to force a response from the authorities.

The Suffragette hunger strike protest, which led to the brutal force-feeding by the authorities, remains one of the most poignant and disturbing aspects of the Votes for Women campaign.

When does what the choice of food we eat, or not eat, become a political act?

‘The Pretty Bar Maid’

All eyes are on the young woman who works in this public house in this satirical print by John Collett. At the centre, an elderly officer raises a spoon from a custard cup to his mouth as he stares at the serving woman. Custards in the 18th century were often eaten from delicate little glasses, and could be creamy or set, sweet or savoury. In the background you can see bowls, bottles, glasses and lemons.

The opening of tea-houses such as Lyon’s in the early 20th century revolutionised eating out by providing women with respectable, safe and affordable places to eat and relax.

Where do you feel most comfortable eating out?

Food, emotions and conviviality

Food can transform a gathering into a celebration, connecting people across time and space.

Iron Age tankard

This 2,000 year old tankard was designed to hold approximately four pints of beer or precious imported wine, far more than one person would drink. It’s made from oak wooden staves covered in beaten bronze sheeting with a small cast handle. We believe the tankard would have been used at large ceremonial feasts where people came together to share food and drink, stories and news would be told and relationships built and renewed. Sharing food and drink on important feast days is common in many cultures.

Which are your most cherished memories of sharing food with others?

Fuddling cup

Fuddling cup

On display in our War, Plague and Fire Gallery at Museum of London, London Wall

Puzzle pots of various kinds were hugely popular in Tudor and Stuart London. This vessel was designed to ‘fuddle’ or confuse since it would have been impossible to drink from without getting wet!

Fuddling cups were a common type of joke drinking pot from the 17th century. The three separate vessels are joined together like a 3d puzzle so that you could not take a drink from any vessel without spilling the contents of the other two.

Can you think of any fun games played with food or drink?

Food heritage, and diaspora groups

Past and present migrations have shaped what we eat and drink today. Coming together to eat or drink can also be a catalyst for change.

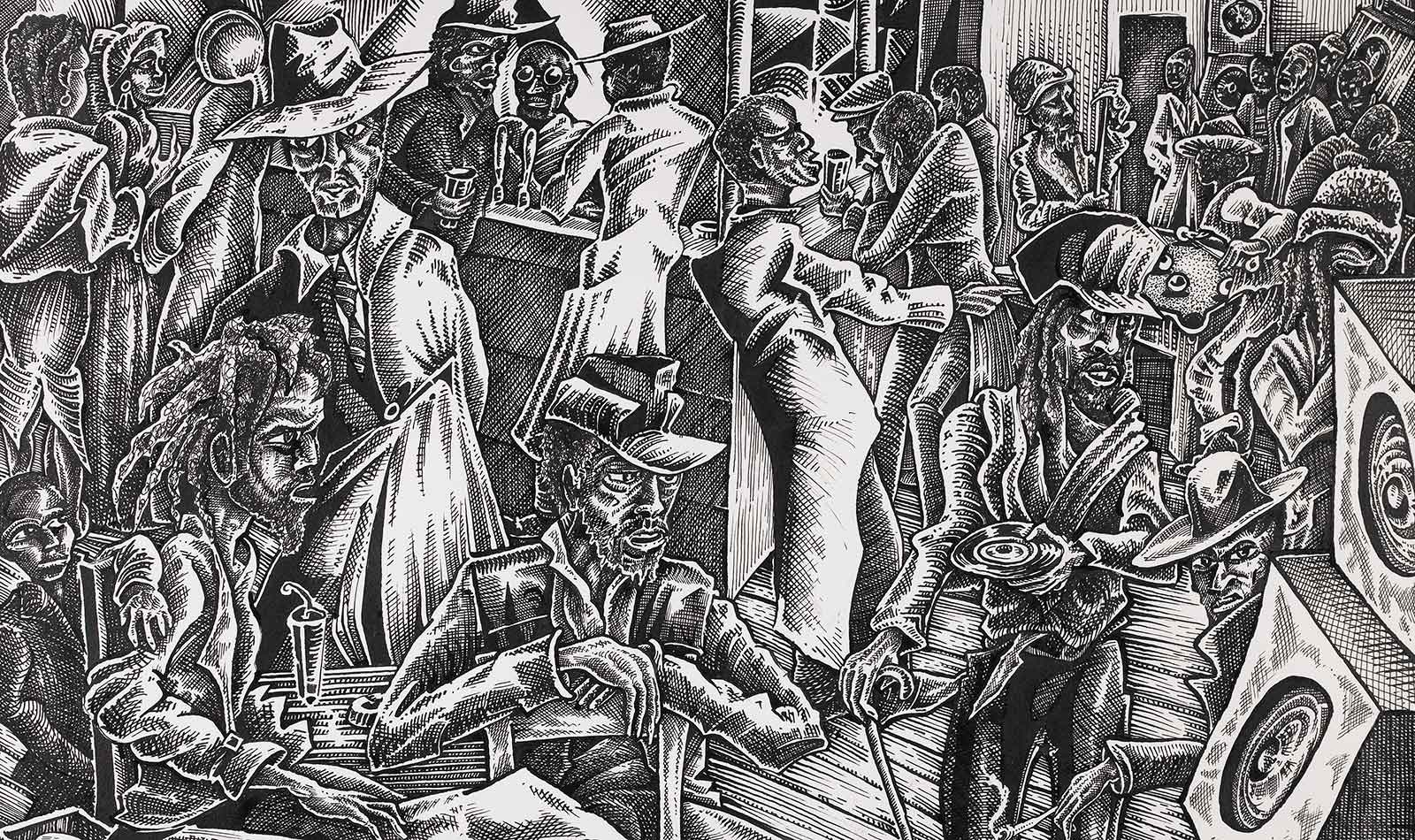

'Atlantic', Coldharbour Lane

This drawing shows customers in the Atlantic pub in Coldharbour Lane in Brixton in 1980. The Atlantic pub was one of the first in Brixton to employ Caribbean women as staff. It became very popular with the local West Indian community, especially as many pubs in London refused to serve African and Caribbean people in the 1950s and 60s. It was a very cosmopolitan space where people from different backgrounds met – indeed, the son of the pub’s English landlord married a West Indian woman in 1965.

By the 1970s the Evening Standard was describing the Atlantic with its spontaneous live jazz as ‘a predominantly West Indian pub, with its customers spilling out of the bars and on to the pavement. The nearest thing in London to a New Orleans bar’. It became known as Brixton’s most visibly black pub, and an unofficial community centre. As the area gentrified, the pub was taken over, refurbished with government money, renamed ‘Dogstar’ and aimed at a more white clientele. It found itself one of the targets of the 1995 Brixton riots, when it was looted and set fire to.

Can you think of a pub that brings a community together?

‘The east view of Wandsworth'

From around 1600, many Flemish and Dutch gardeners moved to the Surrey bank of the Thames to Battersea, Bermondsey and Wandsworth to plant a variety of crops such as cabbages, cauliflowers, turnips and parsnips. This success marked the beginning of intensive market gardening in London, driven by migrants teaching English gardeners new skills and cultivation techniques.

By the early 18th Century common vegetables were very cheap and were beginning to be used by all as an accompaniment to meat. Prior to this they have been used only as a staple food of the poorer classes who couldn't afford meat. By the end of the 18th Century fruit and vegetables were in daily use by every section of society.

Which food or drinks do we enjoy today, thanks to migration?

Food materiality, technology and ingredients

The ingredients and tools we use to prepare a meal can tell fascinating stories about Londoners’ food habits.

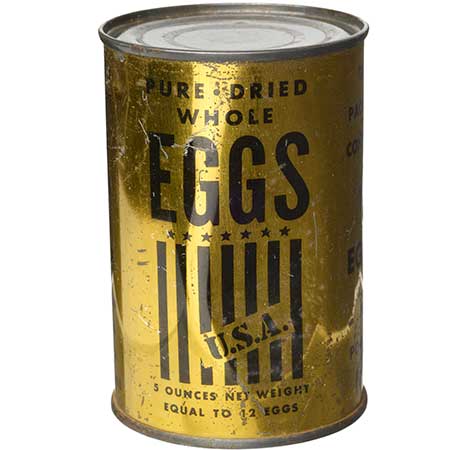

Tin of pure dried whole eggs

Tin of pure dried whole eggs

On display in our People’s City Gallery at Museum of London, London Wall

During the Second World War, a shortage of grain to feed hens led to eggs becoming rationed. Nicknamed ‘Ersatz eggs’, dried eggs began to be imported from the United States of America. This tin contains the equivalent of 12 eggs, and a family would have been allowed to purchase one of these tins every eight weeks, alongside their fresh egg ration.

Government campaigns tried to convince sceptical housewives that they were just as tasty and wholesome as the real thing. Even in London, many families resorted to keeping their own hens to have fresh eggs instead.

Which food substitutes have you tried, and enjoyed?

Medieval ‘spork’

Post-Medieval sucket spoon, 1660-80

On display in our War, Plague and Fire Gallery at Museum of London, London Wall

The fork end of this post-medieval cutlery was designed to spear sticky suckets. Sucket, from the French word ‘succade’ (juicy) was applied to fruits or citrus rind preserved in sugar syrup. The fruit could be speared with the fork while the small spoon was used for supping up the flavoursome liquid. Combined forks and spoons were used in England in the early medieval period, but most surviving examples, like this one in silver, date from the mid- 17th century onwards.

Do you use any special tools to eat particular food?

Reindeer bone

Tool made from reindeer antler

On display in our London Before London Gallery at Museum of London, London Wall

Around 10,000 years ago this tool may have been used to straighten the wooden shafts of arrows. Arrows were vital to hunt birds and animals providing food and other valuable resources. Every part of the animal was used, with nothing wasted. The meat provided food, the hide was made into clothes and shelters, the bone and antler shaped into tools.

This tool was made from reindeer antler. Reindeer roamed through the area that is now London as the country was in the last grip of an Ice Age. This was a time where people lived a hunting and gathering lifestyle. They had a deep knowledge of the landscape, knowing which plants were edible, when fruits would be ripe and plentiful, the movement of migrating birds and animals and how to catch fish. They carefully managed the resources to make sure there would be plenty in future seasons.

Do you forage any food in the city?

Food production, waste and sustainability

By looking at how food is produced, consumed and disposed of we can learn more about London’s past, present and future.

Gardening tools from Roman London

Cultivating plants and crops in and for London’s urban spaces is nothing new. Even when the walls were built around the Roman city, green spaces were part of this enclosure. Whilst wealthy Londoners probably had formal gardens with flowers and fruit trees, the city would also have been home to people with farms outside the walls. These tools may have worked land inside Londinium, or have been bought or repaired here before being used elsewhere.

Do you grow your own food?

‘Tom Sugar Cane, A West Indian’

Tom Sugar Cane, A West Indian

A caricature of Tom Sugar Cane a British Sugar Planter, 1830' by G. Spratt. On display in our Expanding City Gallery at Museum of London, London Wall

This is a caricature of a British sugar planter settled in Jamaica to earn their fortune. His body is made from produce – his chest a barrel of Jamaica Rum, his arms and thighs made from sugar loaves. He sits on a barrel of Molasses whilst enslaved Africans work in fields in the background.

The sugar plantations of the Caribbean and their use of enslaved labour was driven by the British craving for sugar. Even after the abolition of the British slave trade in 1807, it took another 26 years to emancipate those already enslaved. Once emancipated, slaves received no compensation and were expected to work without wages for a further number of years to ‘earn’ their own freedom.

How is modern slavery connected to the production of the food we eat today?

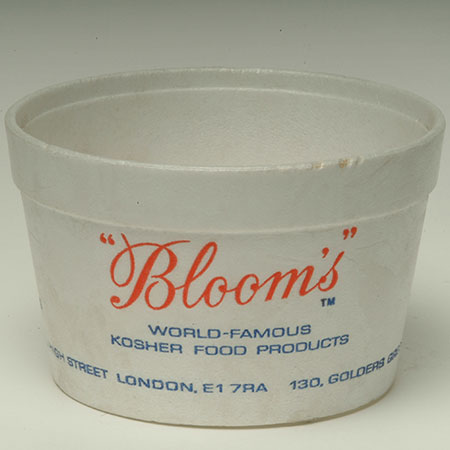

‘Blooms, World Famous Kosher Food Products’ polystyrene tub

‘Blooms, World Famous Kosher Food Products’ polystyrene tub

On display in our World City gallery at Museum of London, London Wall

This polystyrene takeaway container was designed to enjoy a takeaway portion of rollmops, fish balls or other items at the famous Kosher restaurant Blooms.

Blooms opened in Whitechapel, the heart of London’s Jewish community, in the 1920s and established a further branch to serve the local Jewish residents of Golders Green, until it eventually closed in 2010.

More recently, many charities campaign against polystyrene and other plastics which have a detrimental impact on the environment. The EU is set to ban expanded polystyrene, oxo-degradable plastics and some plastic items with its EU Single Use Plastics Directive. In the UK, the devolved administrations will develop their own appropriate measures.

What impact do our takeaways have now on the environment?

Do you want to join in with our food discussions or attend a food-related event? If so, please email us on [email protected].