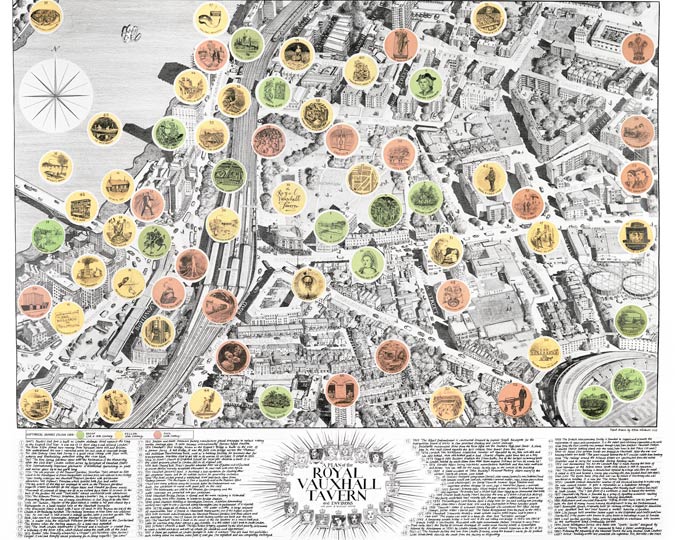

How has London’s LGBTQ+ nightlife changed over time? How might we remember it during a lockdown? When Queen Mary students Georgia, Eve, Kirsten and Keir from Quest Radio began listening to our Oral History collection as part of the Listening to London project, these are the questions they wanted to explore.

Beginning the project in the depths of lockdown when spirits were low and tensions were high, listening to the experiences of the LGBTQ+ community was uplifting for us. At a time when G-A-Y, Heaven and The Dalston Superstore and many other iconic LGBTQ+ spaces remain closed during the pandemic, listening to Londoners’ first experiences of these places was a treat.

The piece we created features LGBTQ+ voices from Oral History interviews which touch on themes of inclusivity, discrimination and identity in relation to nightlife.

You’ll hear about the emergence of gay clubs in London and their importance as uniquely safe spaces for the LGBTQ+ community. Many of the people we listened to describe how club spaces were central in coming to terms with their own identities, from the 1980s to today.

You’ll also hear about the darker side of going out, fears of walking home and discrimination. Moreover, the loss of nightlife for queer and dyke-identifying women and the closure of lesbian bars across London.

We finish by bringing you to our current pandemic; we chose to record our friend sharing the sadness of not being able to go out in London. He talks about missing being able to watch people doing and wearing silly things and the fun he would have with his friends on nights out in London watching drag queens be catty. Even the daft things become so precious when we have nothing to do in lockdown that seems worthwhile.

We hope you enjoy listening to London’s LGBTQ+ stories from then and now, and that you take time to reflect on London’s nightlife with the hope of returning to the dance floor in the future.

Listen here:

‘Narrator’: “This collection is an amalgamation of recordings all centred around the LGBTQ+ community and its relationship to nightlife. It covers themes of inclusivity, discrimination, identity and how the modern world is impacting the nightlife scene. We hope you enjoy this collection.”

‘Victoria’: “I am an artist and a drag queen and I work a lot in nightlife doing performances in club spaces. Gay clubs are so, you know they’re spaces where gay people can go and like you know unlike the rest of the world they can go and be surrounded by people who are also gay, where they won’t get all these micro-aggressions, where they won’t experience homophobia um so the space of the gay club has always been incredibly important and it birthed these beautiful things like drag, um you know these spaces where people can finally be what they want to be makes people also then um do these extraordinary things when they feel safe enough to do them um like transgress gender. I don’t think it would have existed without nightlife.”

‘Judy’: “Visually when I started seeing you know, all the Steve Stranges and Princess Julias and Boy George and all that when they first started dressing up and I started going to the Blitz and then also another club had just opened in London, a big club called Heaven and I hadn’t really come out to myself until then, so when this big gay club opened and I got a job there, then I realized, I mean I knew I was gay but I didn’t know any gay people really on the punk scene but when I came to London and it was all these flamboyant new romantics and I got a job at Heaven gay club”

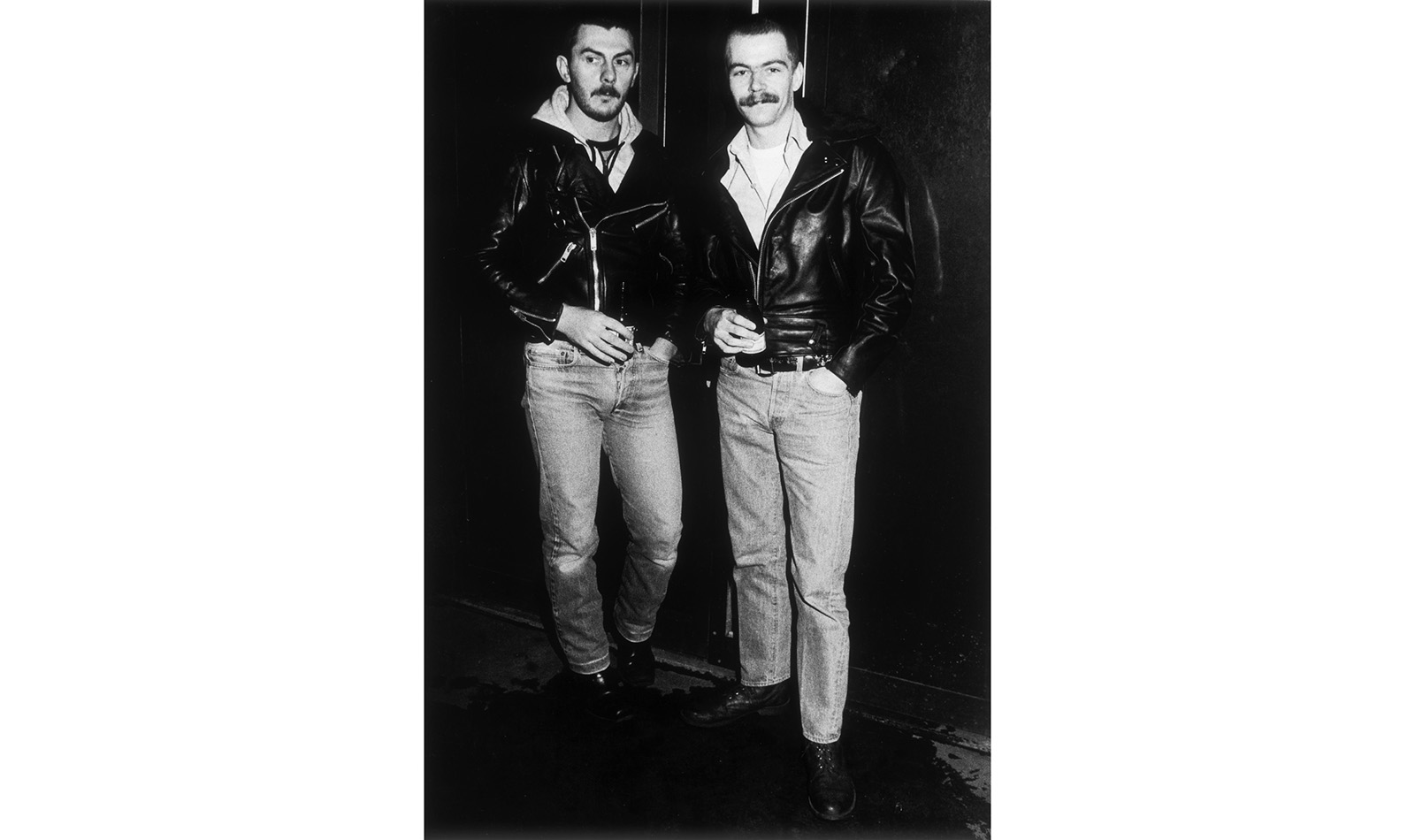

‘Ajamu’: “At 18 I went to my first gay club. March the third 1983. The Gemini club and and I went in it was a Thursday night and there was only kind of one black guy at the club called Desmond and then kind of here and then became my boyfriend that night. And then in turns of the club it was like a white men, the men were coming out wearing leather trousers, white t-shirts and basically caps. And so then so then now, I’m coming to terms with my sexuality now, walking around Huddersfield - a black guy - in leather trousers, white t-shirt, a leather cap thinking this is what gay means.”

‘Victoria’: “This kind of difference and this kind of attention that we pay to femininity and the different ways we pay attention to femininity becomes like incredibly important, um it’s often the case that as I say within nightlife, within spaces like club spaces, um, people like drag queens, people like trans women, um people who are like really outrageous with their femininity, are as I say like applauded. But once, as soon as they step outside, the world becomes like an incredibly dangerous place, um and you know as most people who were socialised as female know you don’t walk home alone if you’re wearing something that’s like a little bit revealing or you know you don’t, or just yea, walking home alone in general is a scary thing. Um and er yeah that sucks. So er yeah, I guess that’s the relationship between nightlife and harassment and it’s kind of a sad situation but I think yea it’s something I’m trying to draw attention to with my work and femininity and how it’s performed in different spaces and how it’s treated in different spaces and often those things are a reaction to each other.

I mean yeah I think London is bustling, but one thing I will say is that like compared to other cities, the um the kind of like, what’s happening for queer like women, um like the lesbian scene is pathetic in London, there’s one gay bar, sorry one lesbian bar and it’s it’s okay it’s not, I don’t know I wouldn’t go there you know, um like there’s not that many nights. When I moved to London there was a lot of lesbian nights, which was like amazing, I thought it was like this great queer woman or like dyke-identifying like utopia, but still there weren’t any permanent, or no yes there were like five lesbian bars and slowly they all closed and the nights kind of dwindled and now there doesn’t seem to be much. Um there is like a growing drag king community which is often a community that happens in lesbian and dyke spaces, um which I think is amazing, but you know there needs to be more like you know I think it’s a little bit, I think it’s a little bit sad and a little bit pathetic, come on London.”

‘Alberto’: “I can remember I can remember there being people around who would say that they were openly gay I mean that it’s certainly because I kind of got caught up a bit in the new romantic thing you didn’t even question it then you know to see George flaunting around in his kimono or whatever pre culture club or Steve Strange or whatever but it was like you didn’t even think about it because you’d been involved in this world for two years prior to that or er yeah two years because that would be around ‘80 right so you are no longer even questioning but it it it just, I’m not even talking about the gay clubs that I was saying earlier but actually going to The Roxy or something you know it wasn’t, The Roxy towards the end became very horrible it became you know the whole punk thing it moved on, all the great bands had got on to the circuit and were doing big venues The Roxy was stuck with I don’t know the sewer rats and the tube the ticket collectors or whatever kind of eight generation punk bands, by the end of ‘77.”

‘Ajamu’: “I knew that there was a gay club there and I’m about six months before I would stand across the main street. ‘Gemini’ was on one street and the black club ‘Venn street’ was on the next street, so you to pass either one to get to the club, from about six months before I stood across the main street and just wanted to go into the club. I just stayed across the main street just watching watching watching, then this night I then decided I’m going to go in. Then I’m I remember seeing a white gay guy going to the club and I just darted across the main street straight into the club and then I was in.”

‘Joe’: “In one sense the clubs closing was terrible because it meant obviously that we couldn’t go places, we couldn’t do things it was the centre of going out in London for me and all my friends, it was the only thing we did together that we really all enjoyed, or at least that we were all good at pretending we were enjoying, we all sort of had a good time being there. We didn’t really club, if this is the word, we more went to watch drag queens be catty and enjoy what other people were doing, there were a lot of people that looked brilliant, I mean some people just looked terrible, you know I don’t know why sort of fishnet crop tops ever became a thing, but we sort of used to sit and sort of bask in the really kind of beautiful, really beautiful people and beautiful clothes and then we would watch drag queens slate naked members of the public and that was kind of our thing. We would go to Heaven and that was what we did, and then all of a sudden it just stopped and I miss more interaction, I don’t miss clubbing. In a way there’s a kind of pressure release that I don’t have to prepare for it, I remember thinking all day what I was going to wear, what I was going to do and I hate that, I hate it so much because I really don’t care, but I have to care because everyone else cares, so it becomes a thing, and suddenly that thing was completely lifted from me. It’s the same with everything, there is no pressure on anyone anymore, but I think for me, it was kind of a relief - for about a week, then it was horrible. And suddenly, everything I thought was horrible, I realised I loved and nothing was as horrible as the thing I have to do now which is nothing. Nothing is as horrible as nothing.”

Research for this piece was carried out by Kirsten Johnson, Eve Caroline Bolton, Keir McEwan and Georgia Wood, from Quest Radio as part of the Listening to London project at the Museum of London, supported by The Esmé Fairbairn Collections Fund – delivered by the Museums Association.

Extracts used in this piece were selected from oral history interviews in the Museum of London’s collection, including London Look (© Museum of London), Punk London (© Alberto Umbridge), London Liberationists (© Museum of London) and Tales of the Night Bus. (Tales of the Night Bus was created and produced by Jo Barratt, Jessie Lawson and Michael Umney, part of ‘London Nights Late: Join the Night London Council’ curated by Flying Object in collaboration with the Museum of London. Supported by Arts Council England).