We’ve all seen London’s iconic landscape on canvases from across the centuries, but what happens if you try to make a less obvious image of the city, one that captures a more personal vision? Here we explore how contemporary artists Gayle Chong Kwan, Anne Desmet and Vera Lutter have all employed unconventional or disruptive techniques to make new work about London.

There are many ways artists can approach London, from depicting familiar landmarks — the Houses of Parliament, St Paul’s Cathedral, Tower Bridge — to capturing those areas with personal meaning.

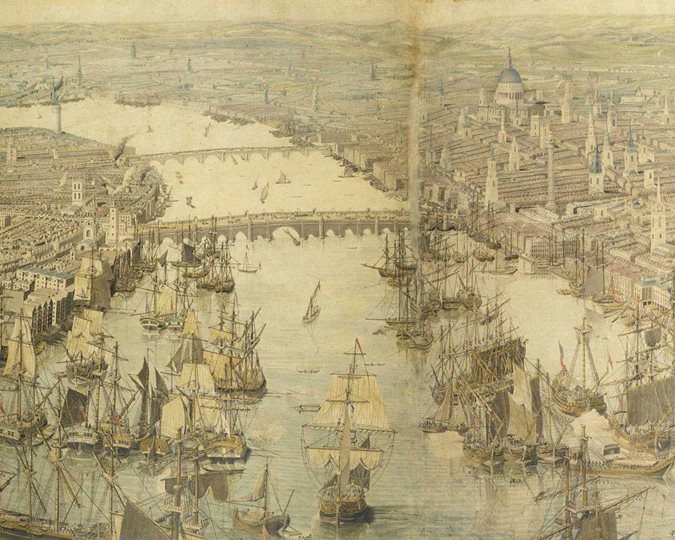

The Thames offers broad, panoramic vistas of the city, which seem to gather together those skyline icons. Unsurprisingly, its banks have often been used as a vantage point by artists. Amelia Long’s watercolour, Blackfriars Bridge (1811), is a good example of such a view. Prominently featuring St Paul’s, one of the defining features of the city, it was painted from around the site of the yet-to-be-built Waterloo Bridge. Alongside the cathedral, the spires of the City churches punctuate the horizon, while the first Blackfriars Bridge spans the river. Dominating the foreground is a now demolished landmark, the Shot Tower.

Blackfriars Bridge (1811)

Amelia Long, Lady Farnborough (1772-1837); Watercolour and pencil on paper. (ID no: 61.74)

But, what happens if you try to make a less obvious image of the city, one that captures a more personal vision? Contemporary artists Gayle Chong Kwan, Anne Desmet and Vera Lutter have all employed unconventional or disruptive techniques to make new work about London. Whether using social media, worn-out linoleum or a room-sized camera, their work provokes us to think about London, place, and history in fresh and surprising ways.

The Golden Tide: Gayle Chong Kwan

Through immersive environments, installations, photographs and films, Gayle Chong Kwan explores themes of consumption, waste and the environment. Her photo series, The Golden Tide (2012), follows the course of the River Thames from London Bridge, through the creeks and marshes of north Kent, towards the farther reaches of the Thames Estuary. Initially conceived as a social media project, it takes a close-up look at the detritus washed up on the river’s shoreline — from tobacco wrappers to banana skins and lollipop sticks.

Over time, Chong Kwan recorded these overlooked strandings, creating a stream of digital snapshots that were uploaded onto Instagram, a then relatively new social-media platform. By applying Instagram filters, she created effects reminiscent of vintage analogue photography.

When displayed in the gallery, as they were for the Museum of London Docklands’s 2013 exhibition, Estuary, the placement of the photographs on the wall reflected where they were taken along the Thames. The specific locations were: London Bridge, Rochester, Queenborough, Sheerness, Birchington–on-Sea and Margate.

The Golden Tide was initially commissioned by Film and Video Umbrella, as part of the project Our Mutual Friends, in which artists used social media to create new work responding to the life and work of Charles Dickens. In its original form, however, as a regularly updated social media feed, the project echoed the constant flow and evolution of the river. Reworking the born-digital images and presenting them as an installation for Estuary was a further development of the project.

Through its tight focus on the mundane, The Golden Tide reveals how our casually discarded rubbish infiltrates the river and wider environment. At the same time, these fragments record the fleeting human presence, almost like a form of contemporary archaeology.

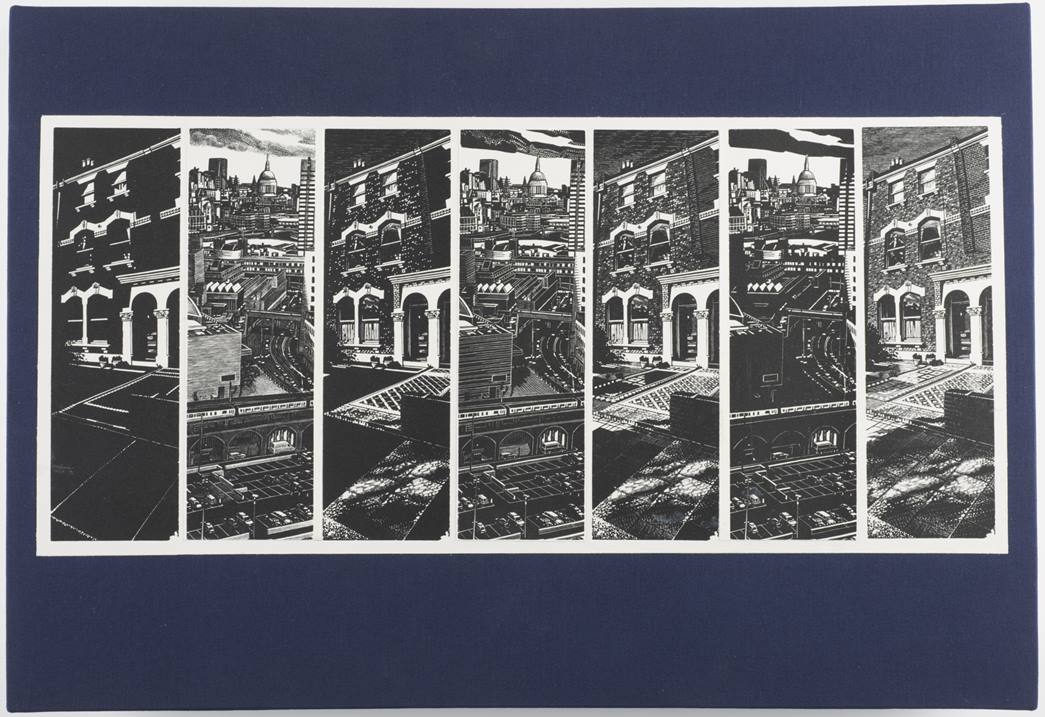

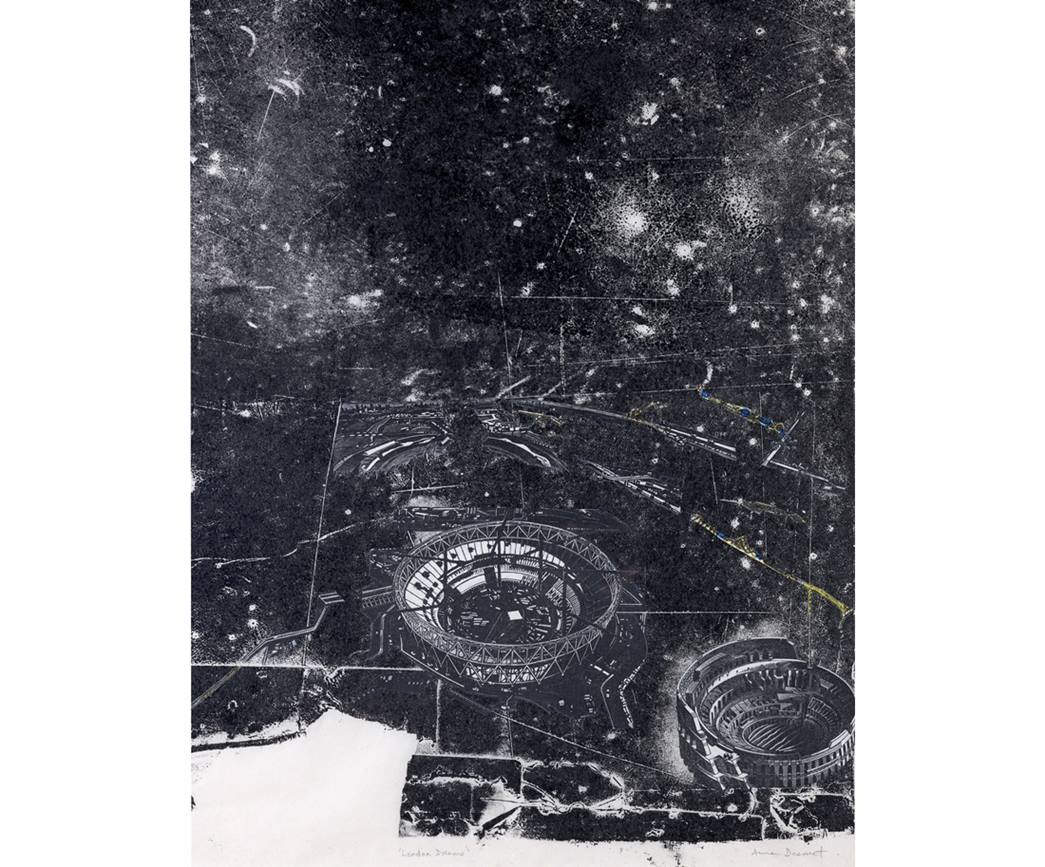

London Dreams: Anne Desmet

Anne Desmet is one of the country’s leading printmakers, working chiefly with wood engraving, usually on the theme of urban or architectural transformation. In 2008, the Museum of London acquired Our London, a book of prints resulting from a project between Desmet and Lauriston School, Hackney. The book included two of her wood engravings, alongside 50 prints by Lauriston pupils with comments about their homes. It is one of two (not identical) versions of the book she compiled using the schoolchildren's prints. The other copy was given to a school in Beijing as a gift from one Olympic city to another.

Desmet’s 2010 print, London Dreams marks a departure for the artist in terms of scale and technique, whilst being closely related the Our London project. In fact, the ground print is the impression taken from a piece of linoleum salvaged from Lauriston School during a refurbishment project. Years of chairs, desks and shoes had scratched and pitted the lino surface so that, when inked-up and printed, it creates an ambiguous but suggestive image: a star-field of marks recalling the nocturnal, lamp-lit city seen from a plane. Onto this, Desmet has collaged wood engravings of the Olympic stadium (under construction and complete) and the Colosseum (a nod to London’s Roman past), and East End houses and roads, creating a composite image around the 2012 Olympics, the changing face of London, its history and connections, and the passage of time more generally.

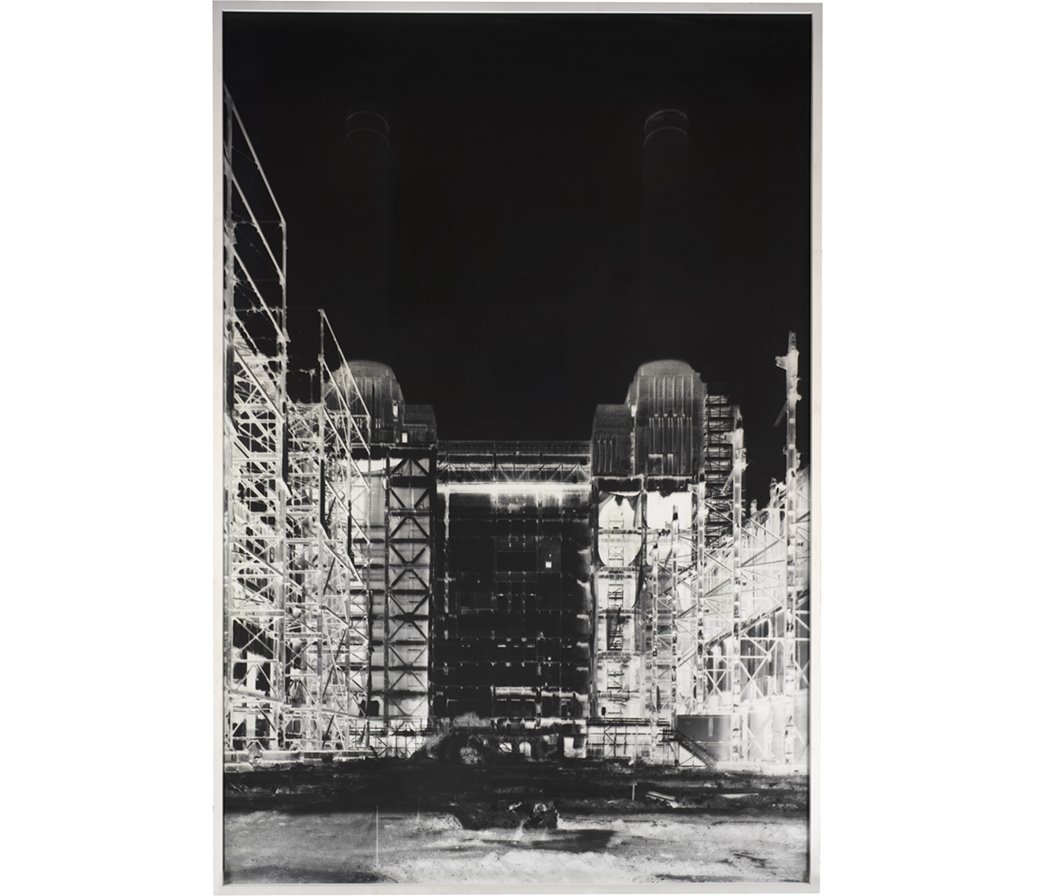

Battersea Power Station XVIII: Vera Lutter

Unlike, Gayle Chong Kwan and Anne Desmet, who examine the city from unusual viewpoints, Vera Lutter takes on one of London’s most iconic buildings, the Battersea Power Station.

Lutter has forged an international reputation for her dramatic, large-scale images, often of industrial sites. Each of her photographs is a unique print made in a custom-made, camera obscura around the size of a shipping container. Light passes through a tiny aperture — in what is essentially a huge pin-hole camera — and casts an inverted image of the outside world onto the back wall, where Lutter places large sheets of light-sensitized paper. The exposure times involved are considerable, lasting days, sometimes weeks, recording not only static features, but ghostly imprints of things in motion.

In 2004, she undertook a month-long project to photograph Battersea Power Station. She was particularly interested in the site as a place in transition, a remnant of the past about to undergo transformation. The outcome was a series of 23 unique, large-scale single- and multi-panel prints, each approaching 7ft tall, documenting the interior and exterior of the empty building. While the exterior shots see the power station from a distance, the interior shots are more claustrophobic and brooding, emphasising the dereliction of the structure, which fills the image. That it has no roof, for instance, and is empty except for the complex armatures lining the walls, lends these photographs an atmosphere of faded grandeur.

Although the monumental size of Battersea Power Station XVIII answers the imposing scale of the power station, it simultaneously conveys an impression of immateriality. Since camera obscuras dispense with negatives, so the final print is itself a negative, rendering the power station curiously insubstantial. Its familiar soaring white chimneys fade into the black sky, whilst the internal architecture is transformed into a skeletal trellis hovering in a void. The image conveys the fragility of the decaying fabric, whilst preserving the imposing character of the structure through rigorous framing, pin-sharp focus and sheer scale of the print.