As focus on the ‘Windrush generation’ has risen in the past decade, recognition of one group of Windrush migrants has remained low — the Indo-Caribbean community. We asked three Londoners of Indo-Caribbean descent about their family histories.

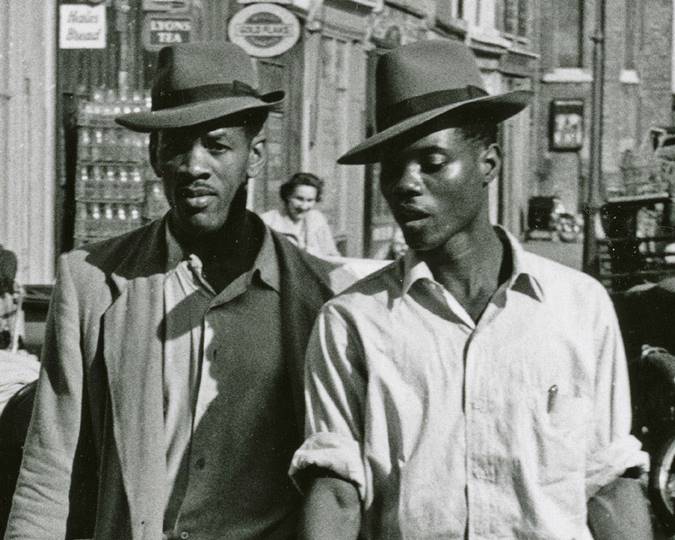

This year, Windrush 75 events are taking place across the country to mark the anniversary of what was the start of around 500,000 Commonwealth citizens settling in the UK between 1948 and 1971. These people were invited here to take up jobs in nascent or struggling industries at a time of rebuilding for Britain after the Second World War. As focus on the ‘Windrush generation’ (as they are often referred to) has risen in the past decade, from both an increased acknowledgement of their impact but also news of the Windrush scandal, recognition of one group of Windrush migrants has remained low — the Indo-Caribbean community.

Many Indo-Caribbeans were part of the Windrush generation but it is difficult to ascertain the number in Britain even today, with no Indo-Caribbean category present on the 2021 census. Perhaps, the most significant reason why the Indo-Caribbean community is so underrepresented is the lack of knowledge here on their history, despite it being intimately tied to that of the British Empire. The Indo-Caribbean community originated with the system of Indian indenture, the focus of our our 2023 temporary display Indo + Caribbean: The creation of a culture at the Museum of London Docklands. Between 1838 and 1917, British planters transported nearly half-a-million Indians under contracts to work on Caribbean plantations. The Indo-Caribbean community that formed from this migration share a culture of mixed Indian and Caribbean influences.

Here we explore the Indo-Caribbean Windrush story through the personal histories of three Indo-Caribbean Londoners — Vedia Maharaj (a psychotherapist of Indo-Trinidadian heritage), Salina Jane (a mixed-media artist of Indo-Guyanese descent) and Jana Ally (of Indo-Guyanese and Egyptian descent working in fashion).

So, why did Indo-Caribbean Windrush migrants come to Britain?

As with many Windrush migrants, the answer to this question is essentially opportunity. Britain was offering jobs to people from the Commonwealth, who were also now British nationals as per the 1948 British Nationality Act and, therefore, welcome citizens. Anthropologist Steven Vertovec, in his 1993 essay Indo-Caribbean experience in Britain: overlooked, miscategorized, misunderstood, highlights that even Indo-Caribbeans from the islands with the biggest Indian presence, Trinidad and Guyana, were underrepresented in fields such as civil service and faced economic discrimination. Britain was then viewed as a place where they could achieve career progression. The Windrush journey of Vedia Maharaj’s family was spearheaded by an ambitious NHS recruit, her mother Anoopia, who came to England in the early 1960s to be a nurse.

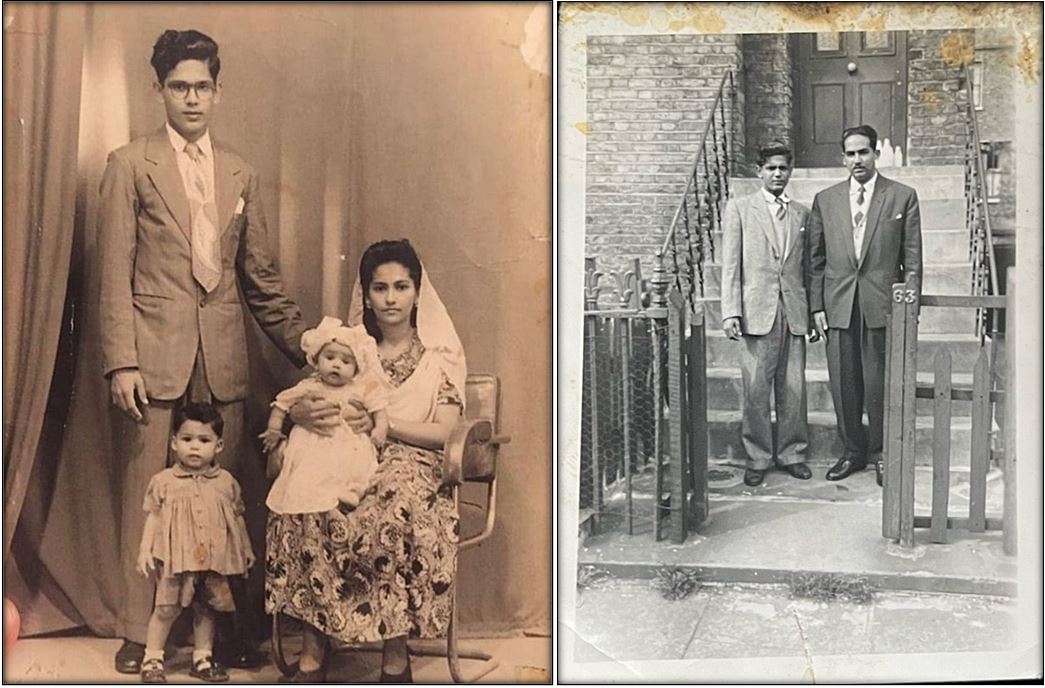

Anoopia’s story hints at another reason for migrating — educational opportunities. Across the Caribbean education was highly valued. Academic David Dabydeen, in The Other Windrush (2021), explains that access to schools had allowed Indo-Caribbean families to escape the indenture system, and examples of educational success included Indo-Guyanese William Hewley Wharton, who graduated in medicine at the University of Edinburgh in 1899. Such stories would have filtered down the generations to Indo-Caribbean Windrush migrants. Jana Ally’s grandfather, Nazeer, emigrated from Guyana in 1952 and she highlights educational opportunities as a key reason for his decision to move.

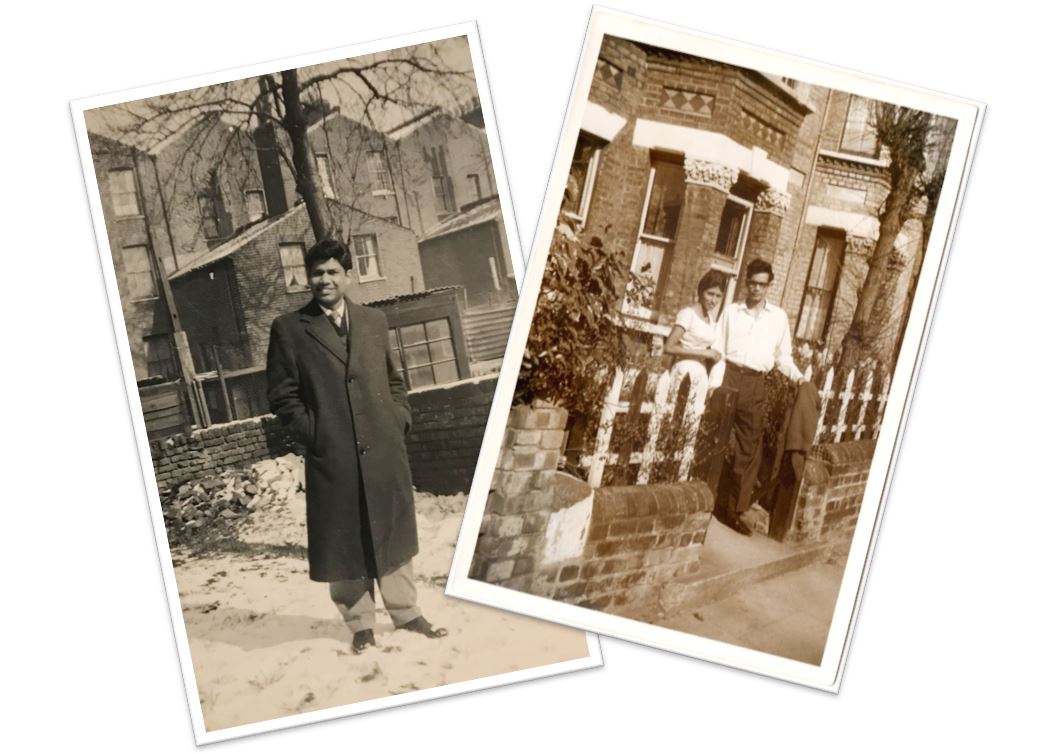

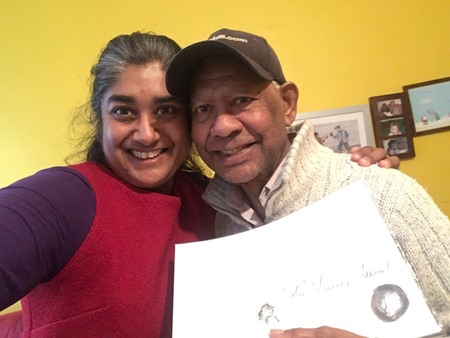

The Windrush narrative has typically only focused on goals of attainment both in explaining the story and in judging the ‘success’ of this migration — a problematic narrative. However, when Salina asked her father Martin why he came to Britain from Guyana, he answered, “I came for the adventure.” Windrush migrants like Martin were also young people who, just like the expats of today, yearned to expand their worlds through travel. It would have been a chance to satisfy curiosity about the ‘motherland’, which rumours said, contained streets ‘paved with gold’. Love and relationships are another important and underrepresented aspect of the Windrush story, and all three of our interviewees see it as central to their migrant forebears’ journeys. Vedia’s father Bramadath, for example, left Trinidad for Britain in order to be with Anoopia.

What happened when they arrived?

Whilst the Indo-Caribbean community in Britain today is often described as disparate, it appears that the first wave of Indo-Caribbean migrants quickly formed important community hubs when they arrived in Britain. Vertovec highlights that places such as boarding houses became hubs for early Caribbean migrants of both Indian and African descent. Salina grew up in the London house that her Windrush generation parents had bought, and has discovered that it was formerly a multicultural hub; a space where Portuguese-Guyanese friends stayed over, where Salina’s father played Dominoes having learned from Afro-Caribbean compatriots, and where a White English couple who lived nearby taught her mother to cook.

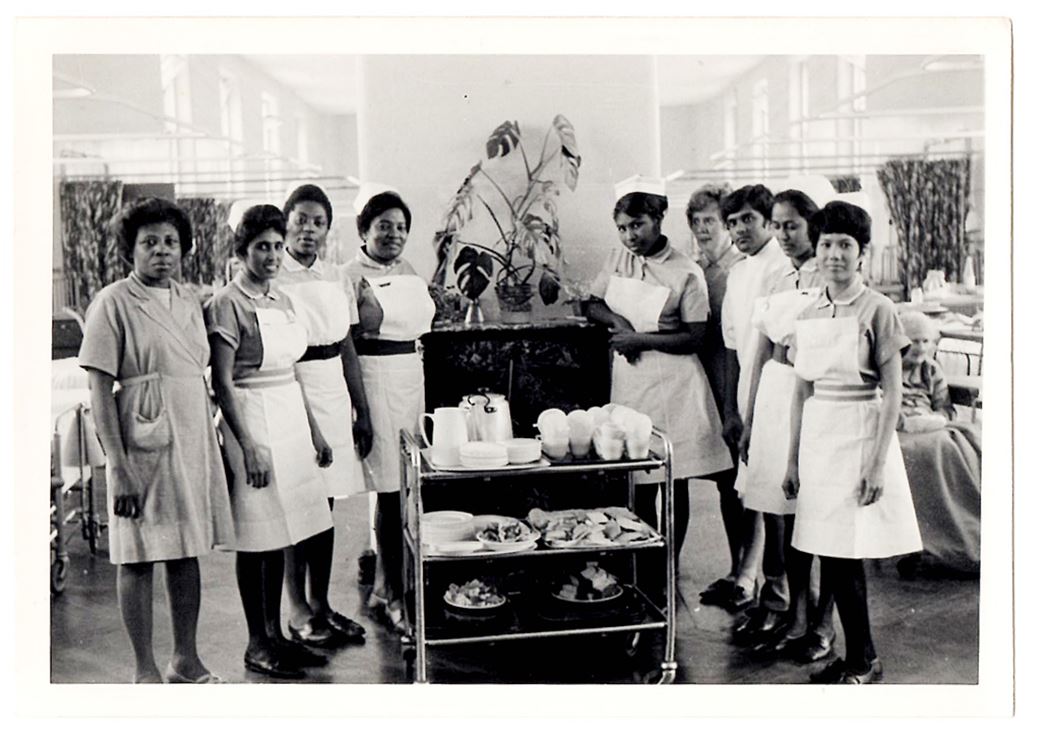

Anoopia in her nurse’s uniform. (Courtesy: Vedia Maharaj)

As time

went by, Indo-Caribbean specific

spaces developed, and Vertovec points out that these

were often religious Hindu or Muslim spaces. Jana’s grandfather Nazeer’s story

provides an incredible example as he helped to set up a Halal meat shop in East London as well as a mosque, which has served the British Muslim community until today.

The need to form specific Indo-Caribbean spaces was also a response to the rejection and racism that the community faced in Britain. As discussed in Vertovec’s essay, Indo-Caribbeans were in the difficult position of experiencing rejection from Asians in Britain (who viewed them as not truly Indian), from Afro-Caribbeans (a continuation of difficulties stemming from British rule in the Caribbean), and racism from White Britons. This discrimination manifested in myriad ways, including at work. Vedia recalls the story of her father Bramadath, who had achieved 3 A-Levels and had worked at a solicitor’s office in Trinidad, applying for Clerical Officer roles in Britain that required only 2 A-levels. He was repeatedly told to apply for lower level jobs or to do the job “in your own country”; he eventually re-trained as a nurse. Anoopia, too, was never promoted to matron. Reflecting on her parents, Vedia now notices how deeply such obstacles affected them.

The generations after Windrush

Diasporic identities are often difficult to wrangle and this has been true for many Indo-Caribbeans subsequently raised in Britain, who have sometimes been labelled a “double diaspora”, and have often struggled to fit into the classifications that exist in British society. Jana also highlights that her father would have been told by his Windrush migrant parents that the family would return to Guyana someday, creating a further sense of instability. This may have been a relatively common idea expressed to the children of Indo-Caribbean Windrush migrants, whose parents often planned for their time in Britain to be periods of accumulation before a later return to the Caribbean, as seen in Vertovec’s essay.

Racism and rejection have unfortunately remained a part of the Indo-Caribbean experience. Salina recalls being called Asian slurs, and all of our interviewees recount the difficulty of having their identities ignored and misrepresented repeatedly. However, many Indo-Caribbeans have put their time into sharing the beauty and history of their community, taking great pride in the bravery of their ancestors who migrated across the world, and their unique culture that blends India, the Caribbean and Britain. The Indo-Caribbean Association had been created by the 1970s and held a festival of Indo-Caribbean culture in 1986.

Salina and her father Martin with her book. (Courtesy: Salina Jane)

Nowadays, Jana writes regularly on Indo-Caribbean identity. Salina creates artwork centred on her family’s history. Vedia worked with The National Archives on an indenture project that resulted in the publication Kuli Dhal Puri – Creative Responses to the Archives from the Indian Indentured Diaspora in Britain. These are just a few examples of the incredible work being done by the Indo-Caribbean community in Britain. Central to celebrating Indo-Caribbean culture in Britain is the need for increased awareness of Indian indenture as the origin story of the community.

All three of our contributors, like many British Indo-Caribbeans, have roots in the Windrush migration and have been active in supporting and recognising the legacies of the Windrush generation. They have, however, continued to struggle to find a place in the Windrush story in which Indo-Caribbeans have so often been ignored. On this 75th anniversary, it is important to recognise and highlight the Indo-Caribbean stories of Windrush. Jana, when asked about her most important message, replies simply: “we exist”.