Artists have played an important role in documenting and promoting the work of the British Red Cross, especially during its early days. In collaboration with the British Red Cross Museum, we look at the works of professional artists from the First World War, some of whom not only volunteered with the charity but also pictorially documented their work, and others who worked with the organisation to raise awareness of its activities or support fundraising campaigns.

During the First World War, many London artists worked with the British Red Cross to support the organisation with its life-saving work — from helping to fundraise for people in crisis to raising awareness of the charity’s vital relief work. They also recorded the extraordinary everyday work of the charity through their art.

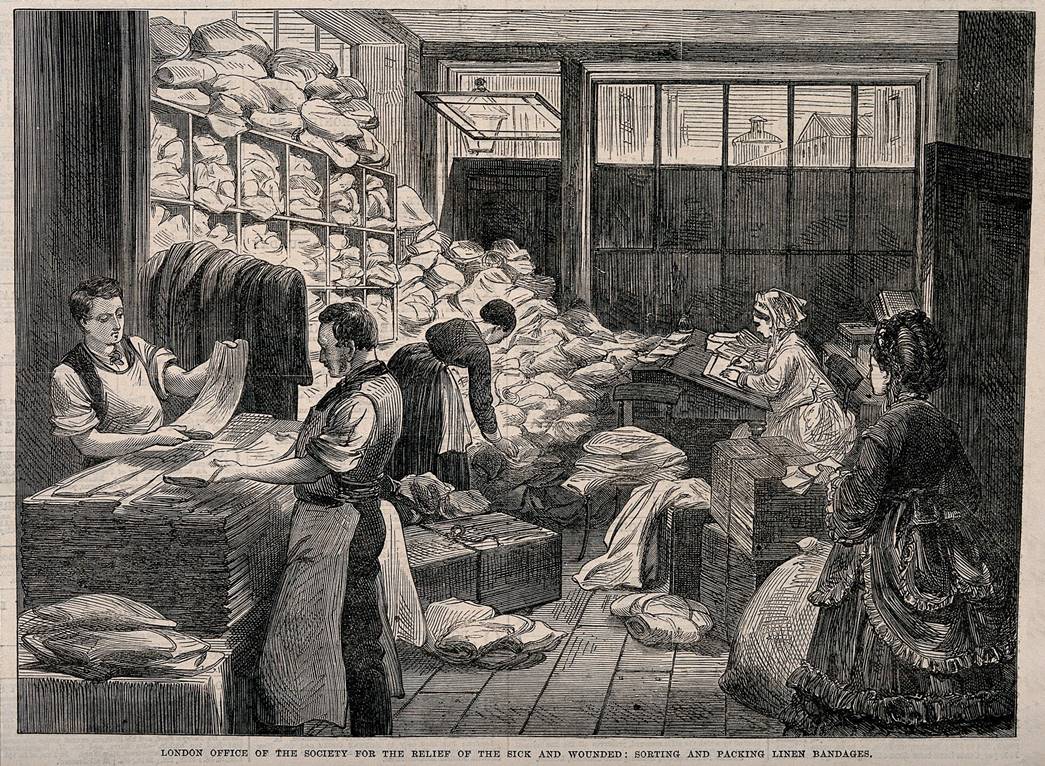

The British Red Cross was founded in London in 1870, following the outbreak of the Franco-Prussian War, and from its earliest days, artists played an important role in documenting and promoting its activities. In 1870, the Illustrated London News regularly reported on the activities of the charity, as depicted in this wood engraving of volunteers sorting and packing linen bandages at the London office at 2 St Martin’s Place, Trafalgar Square, in the Museum of London’s collection. The work of Red Cross personnel and volunteers continued to interest artists as a pictorial subject, and during World War I, both independent artists and British Red Cross volunteers who were working in roles such as nurses and ambulance drivers sketched and painted the charity’s work. Today, these artworks give an insight into the work of the British Red Cross in the past, across the country and continent.

William Monk, 1863–1937

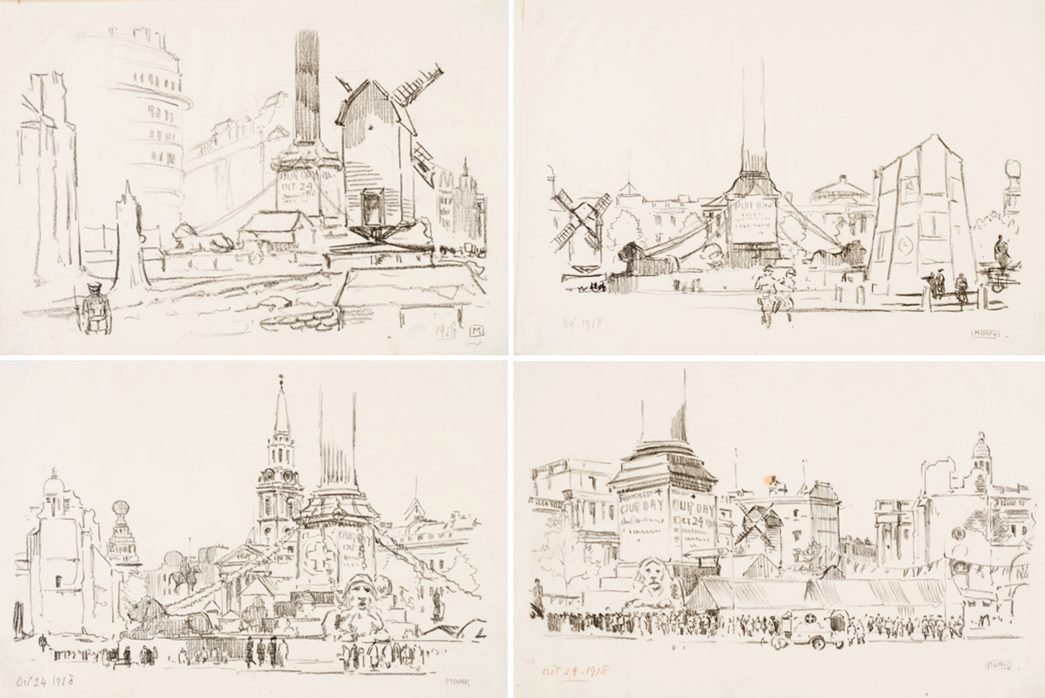

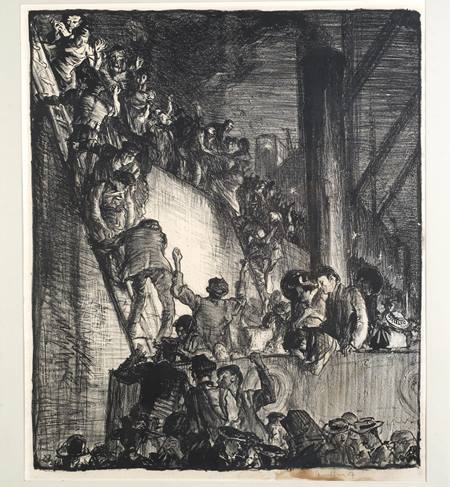

A Red Cross fundraising event called ‘Our Day’ was organised for the first time in 1915 and continued to take place annually throughout the First World War. The idea for this was inspired by Queen Alexandra’s Rose Day, when people showed support for the Queen by buying flowers to raise funds for her favourite charities. Painter and printmaker William Monk, one of England’s most famous architectural etchers of the late nineteenth and early twentieth century, sketched the Our Day activities in Trafalgar Square on 24 October 1918. According to The Times (25 October 1918), the main event was a “Camouflage Fair” with a mock “ruined village”. The ruins can be clearly seen in three of the drawings from the Museum of London’s collection.

The fair began with an auction sale of 400 lots of fruit and vegetables donated by the Covent Garden sellers and growers, followed by the sale of Mr George Robey’s “famous pig ‘Daisy’, given to the Queen by suburban allotment holders and afterwards presented by her to the Red Cross Society.” While Monk, unfortunately, did not draw Daisy, he did walk all around the square to sketch it from each corner. Our Day posters are attached to each side of the base of Nelson’s Column, with tents and other structures — most notably a windmill — surrounding it. In the final drawing, we can see the “sign of the airship” attached to the base of the column to the right of the lion sculpture. This was the marker for Lady Sybil Grant’s hut, which was reported to be “densely crowded all day”. The drawing also includes a van with a sign of the Order of St John, which worked with the British Red Cross as the Joint War Committee during the war.

Joyce Dennys, 1893–1991

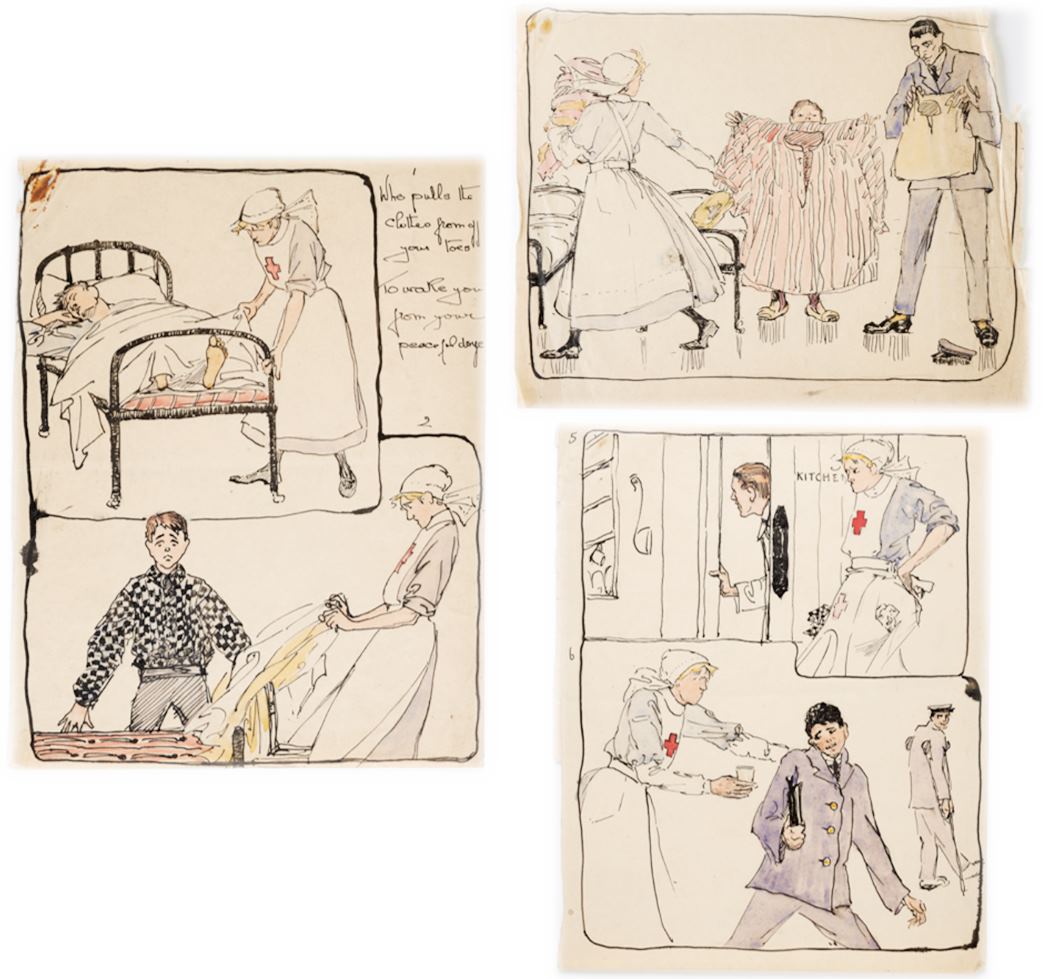

Women artists played a particularly important role in interpreting and documenting WWI, capturing the impact of conflict and the experiences of women who carried out humanitarian work in Britain and overseas. Many female volunteers working with the Red Cross used their art skills to promote and record the work of the charity. In the British Red Cross Museum collection, a majority of the artworks from the First World War are by women artists.

Joyce Dennys was an illustrator, playwright and author of the well-known book Henrietta’s War. When her art studies at the London School of Art were interrupted at the outbreak of WWI, she decided to volunteer as a Voluntary Aid Detachment (VAD) with the British Red Cross from 1914 to 1917. She worked at the Budleigh Salterton VAD Hospital, No.2 Military Hospital in Exeter and Devonshire House in London. She recorded her experiences with various sketches, some of which are now in the British Red Cross Museum collection.

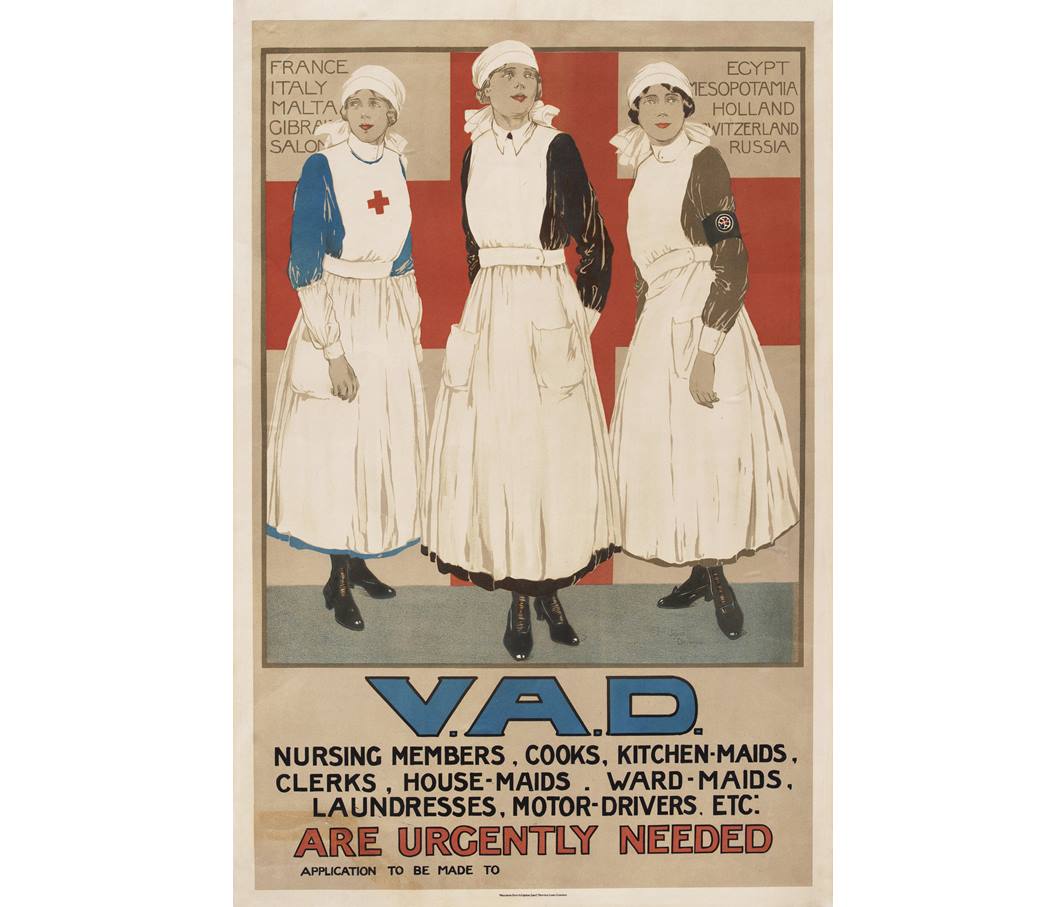

One of Dennys’ well-known works is a WWI recruitment poster featuring VAD members of the British Red Cross, the Order of St John, and the Territorial Force. It’s believed that the response to the poster was so great that no other VAD recruitment poster was needed!

Olive Mudie-Cooke, 1890–1925

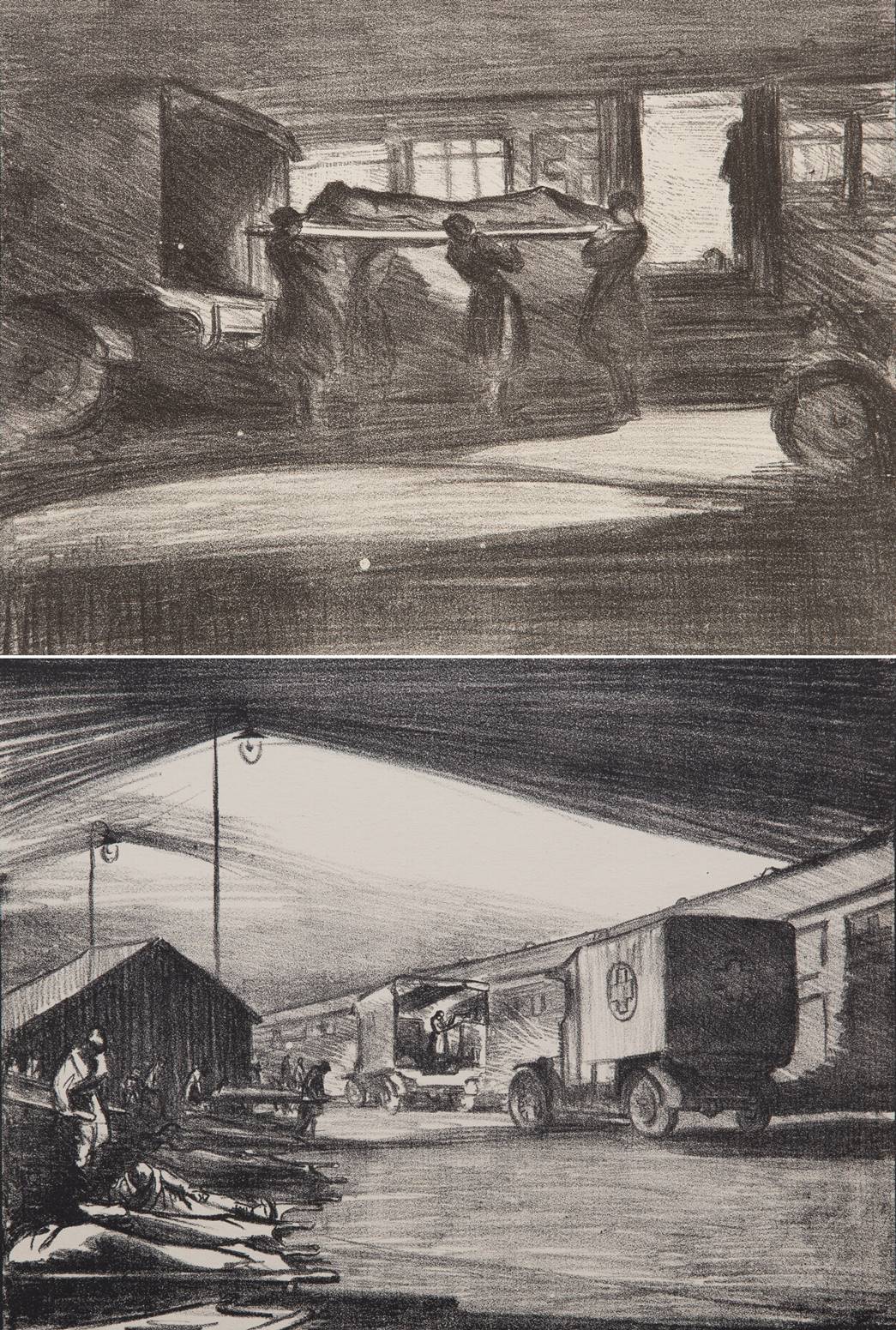

During WWI, female artists were not officially commissioned to enter the war zone. However, some found themselves close to the front line while working in hospitals and ambulance units. Olive Mudie-Cooke was born in West London and studied art at St John’s Wood Art School and at Goldsmiths’ College.

She worked in France and Italy from 1916, driving ambulances for the First Aid Nursing Yeomanry and later the British Red Cross, as well as working as an interpreter. While working as a VAD, Mudie-Cooke began to sketch and paint the scenes she saw around her, including ambulance drivers and medical staff. Her works bring to life the humanitarian work carried out by British Red Cross volunteers close to the front line.

Campaigning and fundraising

The Red Cross has always had a distinctive emblem and is instantly recognisable by the symbol from which it takes its name. Building on this, artists and graphic designers have played an essential role in raising the organisation’s visibility and promoting its campaigns by designing posters, stamps, badges and other products for the charity. Since the early days of the Red Cross Movement, these items became vital communication tools and were distributed widely to appeal to the public for funds needed for services, such as hospitals for the sick and wounded and the provision of relief and medical equipment.

Tom Purvis, 1888–1959

Tom Purvis was widely known as one of the most important English poster artists of his day. He is best known for his work with Austin Reed, London Underground, and London and North Eastern Railway. During WWI, he was commissioned by the Joint War Committee of the British Red Cross and the Order of St John to design several fundraising posters. His striking designs promoted the British Red Cross and raised awareness of the needs of the sick and wounded.

Edmund Dulac (1882-1953) and Frank Brangwyn (1867-1956)

Last Boat to Leave Antwerp, Frank Brangwyn, 1917

(Courtesy PLA Archive)

Artists also designed fundraising products on a much smaller scale. In 1914-15, the Daily Mail and Evening News issued two sets of six ‘Art Stamps’ for sale in aid of the Children’s Red Cross Fund.

One set, designed by French-born London-based book and magazine illustrator Edmund Dulac, depicts personifications of ‘Assistance’, ‘Hope’, ‘Courage’, ‘Faith’, ‘Victory’ and ‘Alliance’ in a stylish Roman-meets-Art Deco manner. The other, by artist Frank Brangwyn, depicts scenes of injured and weary-looking soldiers receiving assistance from Red Cross nurses.

Brangwyn, who had Welsh heritage but was born in Belgium and lived in London, also supported the Belgium Red Cross by selling limited editions of his lithograph of the Last Boat to Leave Antwerp (1917).

Red Cross pins

To further support ‘Our Day’ fundraising activities, artists designed small flags to be sold by street collectors. Small paper flags were sold for a penny, and silk flags were sold for sixpence. Many designs were issued, from simple red crosses against a white flag to images of doves and ambulances.

Individuals from other parts of the British Empire also contributed. For example, Canadian women in London sold tinted maple leaves, while women from New Zealand sold kiwi badges. Australian sellers sold special Australian flags and leather kangaroos. By the end of the war, around £8 million (around £300 million today) had been raised through Our Days.

And the legacy continues

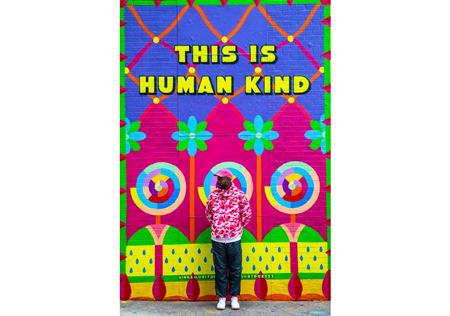

This is Human Kind, Yinka Ilori, 2021

(Courtesy: British Red Cross Museum)

Artists have continued to support the British Red Cross throughout its history by recording the work of the charity, designing posters and other promotional material, and selling works in support of the charity. For example, in 2021, Yinka Ilori MBE was commissioned by the British Red Cross to celebrate the many acts of kindness during the Covid-19 pandemic by painting a 15ft mural on Whitby Street in Shoreditch, East London.

Both the British Red Cross Museum and the Museum of London, among others, have similar examples of how artists have collaborated to document and promote the incredible work of the British Red Cross, the world’s emergency responders.

Both the British Red Cross Museum and the Museum of London have many more related artworks in our collections, so please get in touch or visit to know more.

This partnership was supported using public funding from Arts Council England.