Welcome to The Fatberg Diaries, a series of live updates which tracked how our fatberg samples changed during their time on display.

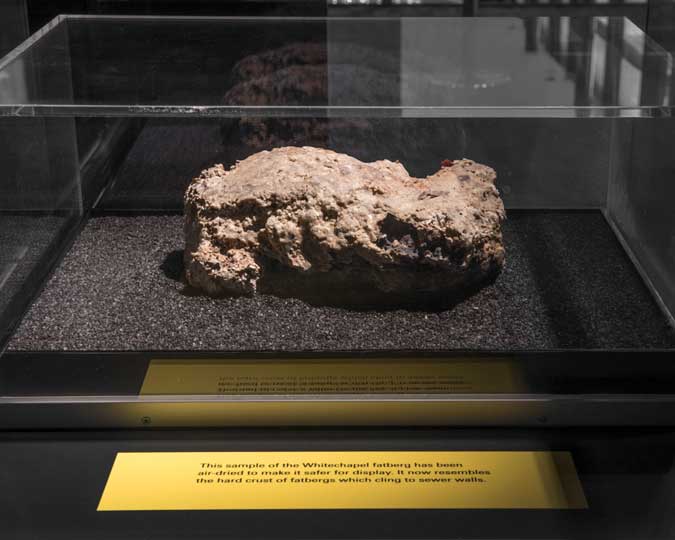

Our fatberg samples are extraordinary - a foul combination of fat, oils and grease, sewage, wet wipes and other rubbish, containing both bacteria and insect larvae. They are like nothing else we have ever looked after. Nobody has ever tried to preserve a fatberg before, so we are having to apply all of our conservation principles to this completely new material.

The Fatberg! display is very much a live experiment, giving us a unique opportunity to observe how this unpredictable material behaves in a museum environment. We are regularly monitoring the samples, and our findings will help us work out whether the samples can be preserved for the longer term, and join our permanent collection.

Current Status: Day 42 (20 March 2018)

Since our last update, the rapid changes to the fatberg that we initially saw have slowed down, as it acclimatises to its new surroundings. Its sweat levels have remained constant, as has its colour.

Fatberg's vanishing trick

However, there has been one notable change: the fatberg’s flies have vanished. The fatberg first started hatching flies in its quarantine period, and continued to do so once on display, so it wasn’t uncommon for visitors to regularly see a few flies flitting about the fatberg. But recently, fly sightings have dwindled and now a fly hasn’t been spotted in several days.

Sharon Robinson-Calver, Head of Conservation and Collection Care at the Museum of London reveals more:

"It’s hard to identify exactly what kind of fly the fatberg hatched, but we think it’s likely the flies were coffin flies, which feed off decaying matter, making the fatberg an ideal home. As a member of the Phoridae family, these flies typically have a very short life cycle, living between 14 and 37 days. As the fatberg has now been on display for 42 days, it’s a reasonable assumption that the flies have died.It is however possible that the flies laid eggs inside the fatberg. We don’t know if this will lead to a second wave of flies, but as there have been no further sightings this would suggest that, if there are eggs, these eggs have not hatched. If eggs have been laid inside of fatberg it is possible that the condensation inside fatbergs case (which is created as the fatberg sweats) has created a very humid environment, which, at this current time, may be preventing the eggs from hatching. We do not know if potential eggs may hatch if fatberg starts to stabilise, or if the condensation reduces. Fatberg remains a very much live experiment."

Current status: Day 14 (23 February 2018)

In the 14 days since the samples have been on display, the larger sample of the fatberg has notably changed in three key areas:

Sweating

Condensation has started to appear in the fatberg's inner case. This is because the fatberg is ‘sweating’. Despite its long drying time there is still moisture trapped within the fatty structure.

Condensation is forming due to the air inside the box being warmer than the acrylic surface. As the fatberg sweats it is making the air inside the box warm and humid, and the warmer the air the more water vapour it can hold. When warm air meets a cooler acrylic surface moisture condenses as small water droplets.

We are only observing condensation on one side of the case at the moment either because the fatberg is holding more moisture on that side or the acrylic box is slightly cooler on one side. The condensation first started in the corners, which is where we would expect to see some heat loss along the joins of the case.

All the colours of the fatberg

Whilst drying out,

the fatberg samples both changed colour from a dark brown, wet mass to a much

paler colour with some small hairline shrinkage cracks appearing on the top of

the sample.

Now, after two weeks on display, the larger fatberg sample is changing again and is darkening in colour from a pale grey to a darker shade of beige. This is again due to the moisture that is trapped inside it.

Bringing new visitors to the museum

During the quarantine period and whilst on display we have also noted the emergence of small flies from the larger sample. The flies can be seen crawling on the sample or the glass, or flying around inside the case. The exact species have not been officially identified but it is likely that these are of the Phoridae family. Phorid flies which look like fruit flies live in sewers and drain pipes and feed on decaying organic matter making fatberg the ideal home.