In September 2017, Thames Water made a horrifying discovery in a sewer below Whitechapel: the fatberg, a 250 metre long, 130 tonne mass of oil and grease congealed with wet wipes and other sanitary products . It’s the largest ever discovered, and the Museum of London wants to put it on display. Sharon Robinson-Calver, Head of Conservation and Collection Care, explains how the museum is tackling the monster fatberg, and how you put a piece of toxic waste on display.

Why did the Museum of London decide to display the fatberg?

The fatberg tells a story about how modern London is changing. The museum’s collection already contains objects from when London’s Victorian sewer system was built, after the city’s health was threatened by water polluted with diseases like cholera. Now, our sewers are threatened by a modern crisis. Eight times every hour a Thames Water customer suffers a blockage caused by items being flushed away or put down the drain which shouldn’t be.

What causes these massive fatbergs?

The British diet has changed in past decades to be oilier, so more fat ends up in the sewers, and more people are flushing waste that the sewer system isn’t designed to cope with. Thames Water advises that only the "three Ps" - poo, pee and toilet paper - should ever be flushed down the toilet.

But another problem is simply volume, with the population of London growing far beyond what was envisioned when the sewers were built in the 1850s. Thames Water estimates that a million people will move to London by 2030, the equivalent of adding a city the size of Birmingham into Greater London. That many people will increase pressure on the city’s water supply, leading to even more problems in the future unless appropriate action is taken. The museum’s collection needs to reflect that, and we can use it to explain the work that’s being done to solve the problems. Otherwise, we’ll have more giant fatbergs. This one could stretch across the length of Tower Bridge.

How will you put such a terrible mass of sewage in a display case?

Well, we’re not actually showing all 130 tonnes. To deal with this fatberg, Thames Water worked in the sewer to break up the tunnel-blocking mass into manageable pieces, which they then extracted through a hose. They drain off most of the water to return to the sewer system. It’s the crust of leftover fat and sewage, or at least a portion of it, that we will display in the museum.

The process for bringing the fatberg sample to the museum is the same as with any other object: we do research to find out what it’s made of, assess its chemical and structural integrity, and how to stabilise and safely display it. We have an extremely skilled team of conservators and collection care staff, experienced with a huge range of materials, but this is a world first.

It’s an especially difficult challenge for us as conservators, because we have to protect not just the fatberg, but also ourselves and our visitors. The fatberg in its current state is an extremely hazardous material, teeming with bacteria and releasing small amounts of toxic gases. Given the amount of rubbish that people pump into London’s sewage system, we can’t know exactly what sort of dangers are lurking within the ‘berg. The sample of fatberg we’ve taken might contain hypodermic needles, condoms, or sanitary materials, and are certainly capable of spreading disease. Making it safe to display is an incredible challenge to be given, and very satisfying to try and solve.

We can apply principles learned working with other, less poisonous objects in the museum’s collection. A lot of organic materials off-gas in the same way as the fatberg samples release toxins. That’s the source of the smell around old leather or wooden furniture. Except most old furniture doesn’t release hydrogen sulphide and carbon monoxide. We’ll have to make sure to stop that off-gassing before it goes on display.

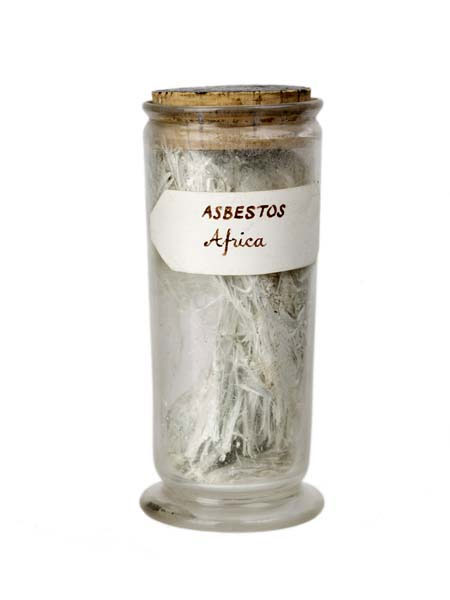

Asbestos sample, 1900

Imported from Africa via the London docks. Just one of the hazardous collection objects our conservators deal with.

Are there any other lessons you’ve learned from working with similar objects?

There are other hazardous objects in the museum’s collection – for example, some contains asbestos, or radioactive materials that make old watch-hands glow in the dark. We follow legislation and have standard procedures in place to protect our staff and visitors.

We’re also used to dealing with wet, organic materials. Some of the best-preserved artefacts from medieval or even Roman London are wood and leather objects excavated from the river. This wet environment keeps the material safe from oxygen which would fuel bacterial decay. In order to keep these objects from deteriorating once out of the water, we remove the water slowly and safely, for example by freeze-drying. Unfortunately, we can’t use this process on the fatberg, because it would permanently contaminate our machinery.

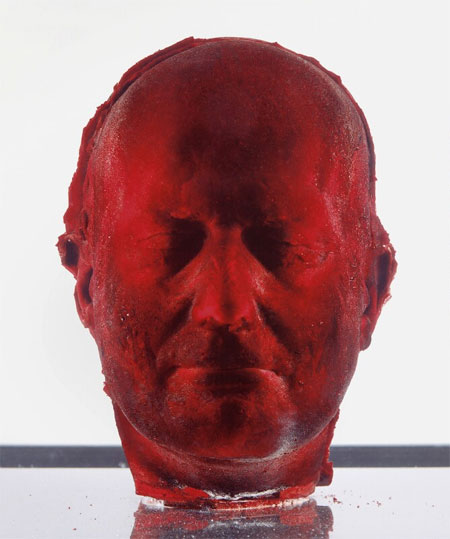

© Marc Quinn. Photography by Todd-White Art Photography, courtesy White Cube, London

Interestingly, a lot of the most cutting-edge preservation work is being done by art organisations dealing with unusual contemporary art. We can learn from the storage and display of Mark Quinn’s sculpture series ‘Self’. Quinn has cast a series of self-portrait heads, each using 10 pints of his own blood. One of these is displayed at the National Portrait Gallery, but they need a bespoke freezer case that keeps the blood at -60 degrees centigrade.

We have also looked at wet preservation, used for artworks containing animal remains like Damien Hirst’s Mother and Child Divided. However, immersing the fatberg in a preservative fluid like formaldehyde isn’t an option, as the mix of oil and sewage isn’t very chemically stable. The fatberg would just dissolve, creating a toxic soup which would be even more difficult to store safely. We also can’t coat it in plastic or rubber. The slightly corrosive fatberg would eat right through, the same way it can sometimes corrode sewer pipes.

So how do you solve a problem like the fatberg?

Our best solution has turned out to be air-drying the material. Our samples were dried in the Thames Water depot at Beckton. The fatberg slowly off-gassed and lost weight as it dried. After this process, the fatberg that our visitors see will be more like the hard, dried mass which sticks to the sewer walls and blocks pipes, rather than the floating mass of excrement and oil in these photographs.

Now that most of the water has evaporated, the fatberg is much more chemically stable, and we’ll be able to put it in our galleries – perhaps in a sealed container within the display case. However we do it, we’ll find a solution, so that Londoners can visit the museum to meet the Whitechapel monster, face to fatberg.

Fatberg was on display at the Museum of London in early 2018, and was added to the museum's peramanent collection.