18 November is the anniversary of the end of the Battle of the Somme- one of the bloodiest battles in human history, and one that has come to define our mental image of the First World War. Almost a million men were killed or wounded at the Somme, and one of them was the first employee of the London Museum, Maurice Edgar Read.

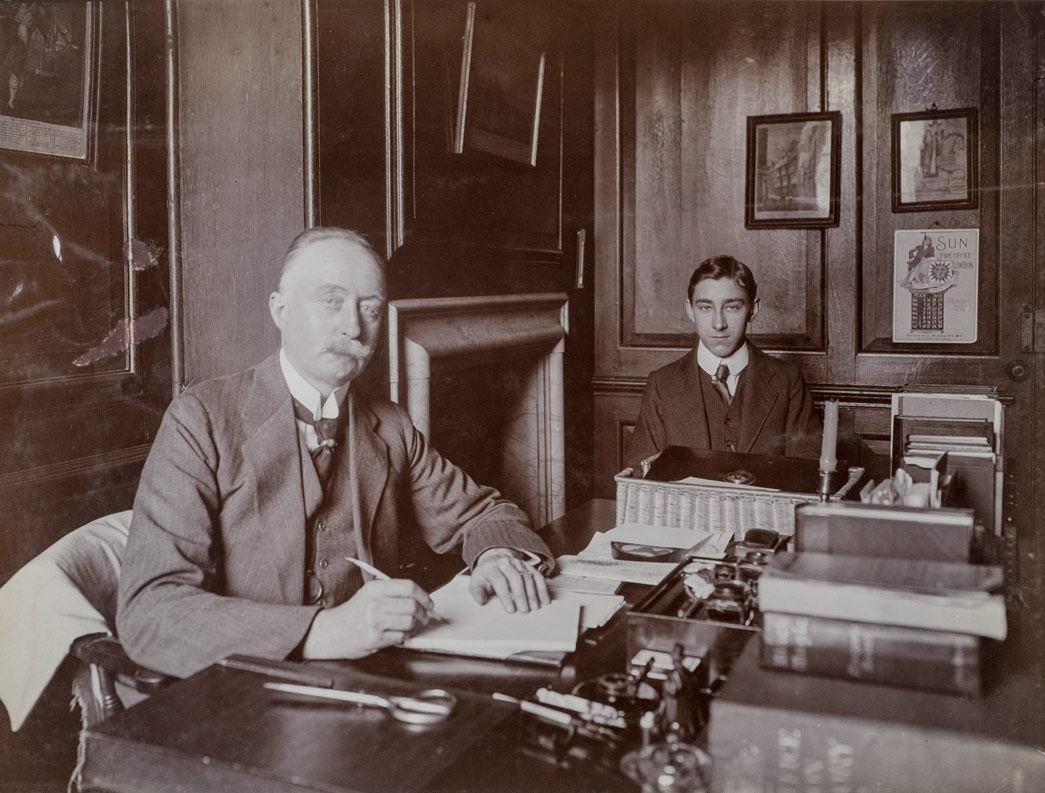

The London Museum, predecessor to the present Museum of London, was founded in April of 1911 by Sir Guy Laking, antiquarian and baronet. Its first paid employee was Maurice Edgar Read, aged just 17 when he started as the museum’s typist. He worked at the museum from its foundation, sending many hundreds of letters as Laking built up the museum’s collection and arranged for the public opening in Kensington Palace on 8 April 1912. Only a handful of documents remain as evidence of Maurice Edgar Read’s life outside the museum- mainly two census records and the British Army documents that chart his brief experience as a soldier. All of these records are held at the National Archives.

Read was 21 years old when he enlisted on the 10th December 1915 at the Stoke Newington recruiting office in north London. By then, the young London Museum had lost half its small staff to the war effort, with two other museum workers signing up. Read joined the London Regiment, which was originally an entirely Territorial Regiment. Initially he was in the 3/23rd Battalion and subsequently was posted to 1/23rd Battalion. The Battalion drill hall was at Battersea, and is the home of the modern City of London Regiment. From Read’s Short Service Attestation we know he lived at 42 Defoe Road, and the accompanying descriptive record shows he was 5 feet, 3 ½ inches tall. He gave his profession as clerk. But Read did not seem eager to head to the front next spring.

The next record is a stern official letter to Read’s home

address from the Stoke Newington Recruiting Officer, stating that “you did not

present yourself for service with the Colours [with the regiment] on the 14th.

February 1916 in accordance with the instructions sent you by post”. The letter

warned Read that if he could not supply a satisfactory explanation for his

absence within four days, “your name will be posted in the Police Gazette as a

deserter from His Majesty’s Army”. At the time, the penalty for desertion was

death.

However, we have a second Short Service Attestation for Read, approved on 4 March 1916, showing that the matter was soon resolved. Did Read have some explanation for his temporary absence that was acceptable to the British Army? Or was this a case of nerves, natural enough in a young man signed up to fight, and tactfully smoothed over by his superiors?

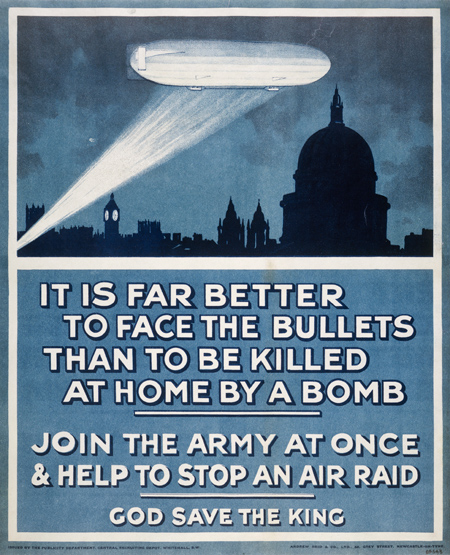

Recruiting poster, 1916

Issued by the Publicity Department, Central Recruiting Depot, Whitehall

It’s tempting to read between the sparse lines of these

documents, to try and imagine the character and opinions of a young man who has

left so little of himself for us to discover. Perhaps Sir Guy Laking put

pressure on his young clerk to take part in the fighting, as the older man

wished to do himself. If he did, it would have chimed with the mood in London,

where the Order of the White Feather encouraged women to publically give

symbols of “cowardice” to men who were not in uniform, to shame them into

joining up.

Like all other national museums, the London Museum closed on 1 February 1916, and would not reopen for the duration of the war. Perhaps this encouraged Read to enlist, but he may also have been anticipating national conscription. Passed by parliament in March of 1916, this made military service compulsory for all unmarried men aged 18-40. By then, nearly two million men had volunteered, for reasons ranging from patriotism to unemployment to a wish for excitement. Ultimately, we cannot peer into the minds of the dead. We must allow the records to speak for themselves.

After the Battle of Flers-Courcelette, 1916

The battle in which Maurice Read was killed; City of Vancouver Archives, public domain.

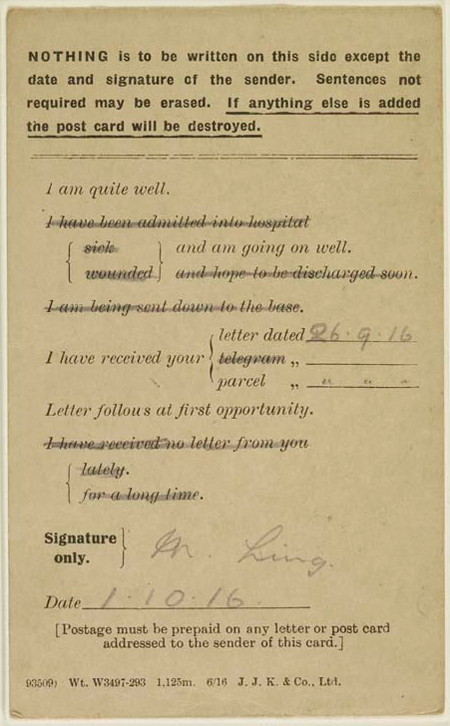

Field service postcard, 1 October 1916

Sent from the trenches. Pre-printed with a series of messages for sender to choose between. ID no. 2007.1/51

The painfully short “military history” section of Read’s enlistment report has just two entries: Home from 4 March to 3 July 1916, while he completed his basic training. Then, Expeditionary Force France, 4 July 1916. Maurice was heading to his battalion, just 3 days after the Battle of the Somme began to rage on 1 July 1916.

The terrible slaughter of the first day, which alone killed 19,240 British soldiers, was stretching into a punishing campaign that was to rage until mid-November. The largest concentration of artillery in history, poison gas, and the first use of tanks combined to turn the muddy fields around the Somme river into a horrific battleground. Read entered it on 21 July, when he joined his unit. He was killed in action on the 16 September 1916. The 23rd Battalion of the London Regiment were at that time on the offensive in the Battle of Flers-Courcelette, during which 29,376 Allied soldiers (and an unknown number of German ones) died to move the front lines about 2300 metres.

The remaining documents at the National Archives were all created after Read’s death, and outnumber the records of his life. Active casualty service form, next of kin records, record of the commemorative plaque and scroll issued on the death of a serving soldier- each gives us more details of Maurice Read’s short life.

Read’s next of kin reveals him as the youngest son of a large family, with three older brothers and three older sisters, his mother dead. He had lived at home with his father John, to whom the deceased’s personal effects, if any, were to be sent at the address of 42 Defoe Road. Of the seven Read siblings, only Maurice still lived with his father. He was the baby of the family, next oldest brother Arthur being 33. The file’s final document is a telegram, sent by John Read to an officer in his son’s regiment:

February 20th 1917

[To] Major G.F. Bartlett

Dear sir,

I duly received “Disc” [Maurice’s identification disc] by registered letter, belonging to my late son [illegible word] Maurice Edgar Read. I shall trust that you will forward me any other of his belongings, if they come to hand.

He was five years at London Museum, Lancaster House, Kensington Palace, and it is painful to think this is the only article found belonging to him.

Yours truly,

John George Read

The Commonwealth War Graves Commission lists no known grave for Maurice. Perhaps a fellow soldier recovered the identification tag when Maurice was killed, and the body was later blown up by an artillery shell, lost in the mud of the Somme, or simply buried in an anonymous grave. It is unlikely that John ever received any more of his son's belongings.

On this sombre centenary, we remember Maurice Edgar Read, and the more than 17 million others who died during the First World War.