Our City Now City Future season asks how to keep cities liveable into the 21st century, and what lessons Londoners can learn from urbanists around the world. We asked Ruth Calderwood, head of Air Quality at the City of London Corporation, how to make the city breath easy in 2100.

Can cycling help to clean up London's air? We're collecting images of Londoners on their bikes in our #LondonView campaign. Send us your photos on Twitter, Facebook or via our website with #LondonView.

Clean air is an essential requirement for life on earth. When air becomes contaminated, it can lead to illness and even death. Throughout its recent history, it’s likely that London has never experienced very clean air. This is partly due to the capital's location, situated in a river basin surrounded by low hills. This local topography can lead to the development of mists or fogs which trap air pollution.

Traffic in smog at night, 1956

© Henry Grant Collection/Museum of London

One of London's less salubrious nicknames is 'The Big Smoke'. This smoke was initially cause by wood burning, and then coal. In the 19th and early 20th centuries, smoke from coal burning combined with local mist and fog to cause the famous London ‘pea-soupers’, fogs named for their thickness and colour.

In 1952, a particularly bad pea-souper called the Great Smog choked London for 5 days. The smog led to the death of at least 11,000 Londoners, with many more thousands becoming seriously ill. Politicians finally took note, and two years later the City of London Corporation introduced local legislation to ban the production of smoke in the Square Mile. Two years after that, the government followed suit with the national Clean Air Act 1956.

The Clean Air Acts were very effective in dealing with air pollution caused by the burning of coal. London slowly moved over to the use of natural gas, which is much cleaner. Power stations closed down. Electricity production, and its associated pollution, was moved out of London. The air was finally getting cleaner. Unfortunately the problem was very soon replaced by pollution from a different source, the motor vehicle.

Cyclist's smog mask, 1995

Designed to filter out noxious particles in the air.

London’s air today is still contaminated. One of the main differences from the days of the pea-soupers is that the air pollution is largely invisible. It does, however, still have an impact on health. Numerous studies have linked long term exposure to air pollution with a wide range of illnesses including cancer, respiratory and heart disease, as well as diseases of the brain including dementia. London’s air quality is also restricting the lung development of its children.

Today’s problem isn’t coal or wood, but diesel. It’s widespread use has caused a problem for urban air quality. However, the good news is London’s air quality is once again improving as concerted efforts are being made to clean up the city's vehicle with alternative fuels such as gas, electricity and hydrogen.

There is however a new threat looming; electricity production is being brought back into the City, and on a large scale. Combined Heat and Power plant are springing up in new developments; companies are running back up diesel generators in times of peak electricity demand. Data centres are springing up over London and these all have huge diesel powered generators ready to fire up if there is a power outage. While we all have our eyes on cleaning up traffic, there is yet another source of pollution ready to take its place.

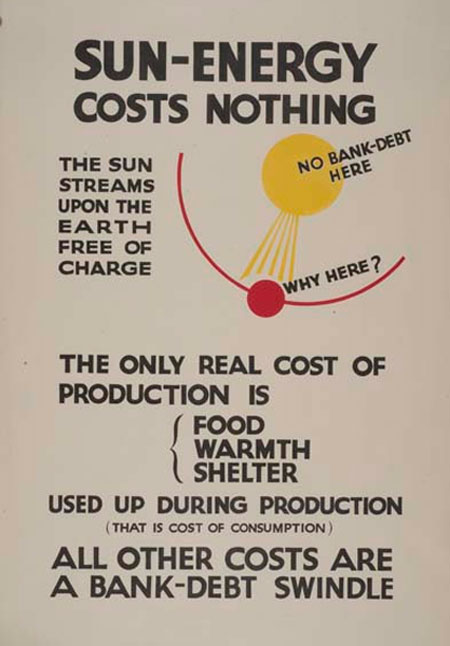

Sun energy costs nothing, c.1948

Poster from the Social Credit party, promoting solar energy.

London is a huge city that is set to grow in size. We need to have a serious debate about the source of the energy required to support it. An ever-increasing growth in the use of new technology puts further demand on energy resources. We need to explore all options of producing clean energy. We also need to find more effective, sustainable ways to store it.

Mankind is very adept in finding engineering and technological solutions. The London of the future will find more efficient ways to harvest and store different form of renewable energy. The whole city may one day be covered with photovoltaic cells adapted to maximise the harvesting of solar energy through London’s cloudy skies. Kinetic energy may be captured and utilised to power equipment as people and vehicles move around the City. Energy from magnets and even noise may well form part of the solution. Londoners are likely to be making use of the energy stored in the tidal Thames.

Over the next century London will continue to grow and people will become more reliant on, and their lives more interwoven with, technology. Goods may be moved around in the air as ground space dwindles, and more areas are pedestrianized to cope with the rising population. Car ownership will be very low as driverless cars are called upon to take people where they need to go.

Smart technology is likely to play a large part in a future London making air pollution visible in the street. Technology will help develop solutions to London’s poor air quality but it may also bring problems, as any new devices will need to be powered. We need energy that’s generated without combustion so London finally gets the clean air it deserves.

Ruth Calderwood is writing in a personal capacity. This article does not necessarily reflect the views of the City of London Corporation.

Learn more about how cities around the world are tackling their pollution problems in The City is Ours, a free major exhibition at the Museum of London until January 2018.