2016 sees the Punk.London series of events and shows around the capital, celebrating 40 years of subversive culture. The Being Punk display at the Museum of London was designed by students from Central Saint Martins to reflect the life of everyday punks. We interviewed the students to find out how they created Being Punk, and what punk means to them.

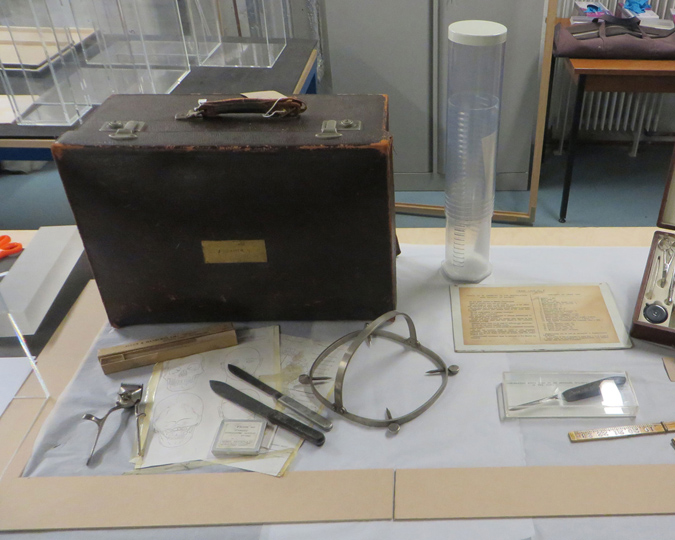

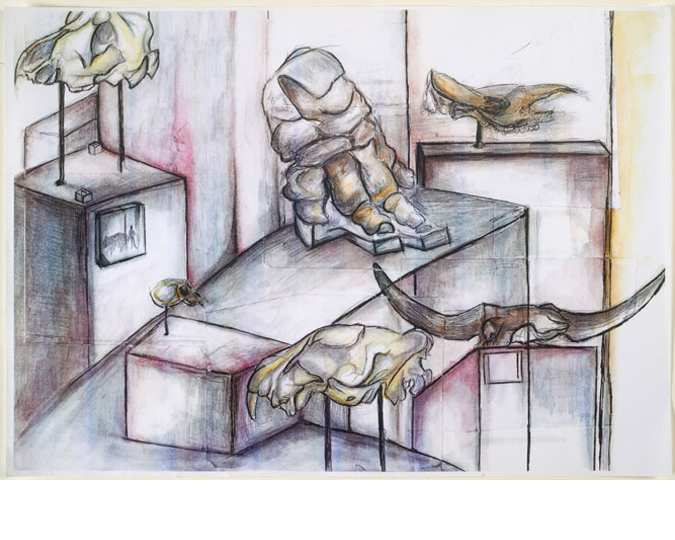

A Show Space display at the Museum of London, Being Punk tries to create a window into the lives of everyday punks. Three display cases, decorated with clothes, photographs and objects from the museum's collections, each represents a different moment in the lives of people who were inspired by punk style, music or politics. The first case is a 1970s-style bedroom, with a punk outfit on a hanger, ready to be put on. The second uses photography by Henry Grant to show punks hanging out on the street, and the third represents a toilet stall in a nightclub. A fashionable, punk-inspired dress and high-heeled boots are hung up, as an imagined punk gets ready to change from her street clothes into her clubbing outfit.

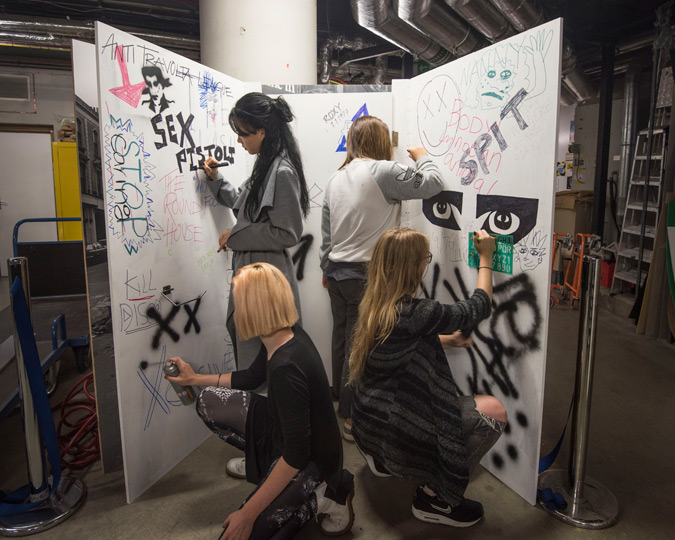

These imaginative displays were created by seven students from Central Saint Martins, studying Fashion History and Theory. Ann-Marie Voina, Eleanor Kirby, Eun Ji Cho, Naomi Richards, Siuming Shang, Sofia Best and Elly Wood created the concept and helped choose and put together Being Punk- right down to decorating the walls of the nightclub case with authentic period graffiti!

What inspired the designs in Being Punk?

Sofia Best: Everything started with research. We looked at a lot of original photography from the 1970s, of locations that were important to punks- places like The Roxy, in Covent Garden, or of Brixton in the early 1980s. We wanted to capture the experience of ordinary people who were part of the punk movement or saw themselves as punks.

Naomi Richards: The only one we're sure of is the bedroom - it uses genuine 1970's wallpaper, and all the clothes come from the same person who was a young punk in the 1970s. It's like a small window into someone's life as a punk. The other cases are a bit more imaginary- they're more inspired by punks.

Sofia Best: Most of the phrases we’ve graffitied onto the toilet stall, for instance, are those that punks themselves said or listened to- we’ve got song lyrics, political slogans, phrases from T-shirts, that sort of thing. One design reads “Anti-Travolta League”, which we found on a badge that was donated by Eleanor's father. We also carried out dozens of oral history interviews with people who were- or are- part of the punk scene. So some of the display come from those. We have lyrics of songs that they mentioned, things they said or remembered. You can actually listen to two interviews with punks as a part of the display itself- one that we collected, one from the museum's collection.

Eleanor Kirby: Sniffin’ Glue [a punk fanzine] was something that I quickly found and became quite attached to. It was wonderful to have the opportunity to interview Stephen Micalef, a former editor of the zine.

While our initial research inspired the concepts for the cases, the content was really directed by the oral history interviews that we carried out. It’s easy for those who were not involved to view punk quite impersonally, so carrying out interviews brought everything to life. It added colour to the black and white photocopies in the zines, and introduced us to nuances we hadn’t considered before.

I spoke to Max Hamilton, who was a young punk in the 1970s. He spoke about what clubs he went to on specific days- my rational mind quite liked that punk had some routine to it! He also said that his parents were really accepting of his involvement with the movement, quickly dissolving our assumptions that older generations were disgusted by the punk movement.

A lot of the impact of our research was probably quite subconscious. We made a lot of visits to the museum’s costume store, where Beatrice read us letters she had received from people who had donated their clothing. We also held a "punk show and tell" event, which meant more first hand accounts, and even some photographs. It didn’t make it to the display, but someone brought a photograph of a squat he lived in near Kings Cross, in place of a mirror he has graffiti’d a square with “mirror” inside it. He also mentioned that a lot of people used Wimpy cafes as landmarks, a glorious detail!

Elly Wood: By using images from the time period we were able to build up an idea of what a "typical" punk's surroundings would have looked like. Simple interior shots helped us with the design to create an environment that would have been familiar to punks of the time.

Do you think this display reflects the spirit of punk?

Elly Wood: I feel as though the display reflects everyday punks, which is what we wanted to do. The first case, which we called "getting ready", displayed what the room of an ordinary punk would look like. I also think the display shows how the punk movement was a mixture of a lot of people, from various backgrounds.

Siuming Shang: I didn't know much about punk before I started this project. I thought of it chiefly as an aesthetic thing, a style. So it was fascinating to meet people who had lived a punk lifestyle, and discover that there had been this mindset. We tried to create authentic punk scenes.

Eleanor Kirby: I hope that the display imparts a narrative to visitors. We wanted them to adopt their own punk mentality, getting them to think about the experience of customising their clothes, arranging a meeting place before social media, getting changed in the club toilets so your parents couldn’t comment on what you were going out in, and the flyers that would help you plan out your next night out.

Without trying to sound too over-analytical, we wanted to highlight the lack of technology in a very sociable movement. I think we’ve lost some skills in gaining social media, I wouldn’t know how to find out about a gig without a quick Google. Of course, the creativity of punk came from looking for something to fill your time with. I don’t think subcultures are as effervescent nowadays.

We don't need no education

Ann-Marie Voina, Naomi Richards, Siuming Shang and Sofia Best prepare the Being Punk display.

Do you consider yourself to be part of any modern subculture? Something comparable to punk, that you'll still remember in thirty years time?

All: No!

Naomi Richards: I don’t think I’ve ever been part of one. I feel like there’s been a generational shift- our generation has less well-defined social groups.

Elly Wood: I completely agree. I feel as though today there are no strong subcultures that can compare to the lasting effects of punk, I feel as if it is unique in the way that it has shaped the rest of peoples lives and still lives on.

Sofia Best: I feel like there are very self-conscious subcultures like goths, but there are mostly some diffuse styles. Indie, emo, hipsters- those aren't really very coherent groups. They may have a loose sense of fashion or similar tastes in music, but they don't have any real guiding philosophy, any sense that they have the kind of broad cultural impact that punk did.

[We had a brief discussion of whether Naomi's glasses could be described as "hipster"].

Eleanor Kirby: It’s hard to define today’s subcultures, but I find a lot of my style (whether visually expressed or not) comes from film because of its total inclusion of all aspects of culture, they’re pre-packaged with a soundtrack to suit the costumes – everything informs everything else.

I would say that online subcultures are also quite popular today, which sounds terribly sad. Things like Tumblr’s obsession with “Lolita” and imagery to do with female innocence is something that I don’t think translates outside of its online presence. That “subculture” seems to be quite contained within 2D imagery, rather than over-flowing into dress.

Do you think punk is relevant today?

Naomi Richards: You can definitely still see the influence of punk.

Sofia Best: Yeah, Naomi's wearing ripped jeans and a leather jacket.

Naomi: Not deliberately! I didn't try and dress "punk" this morning. But that does show how the fashion has gone completely mainstream, I think.

Sofia: And the message of punk is also relevant- perhaps more so now than in decades. The idea of doing your own thing, ignoring the rules about what you couldn't say or do, it captures a feeling of spontaneity that's still very exciting.

Eleanor Kirby: Punk’s relevance lies within its power to interest such a variety of people. While true punks might be upset by the fact that it has been diluted into today’s commercial fashion and music, it’s a tribute to the strength of its iconography.