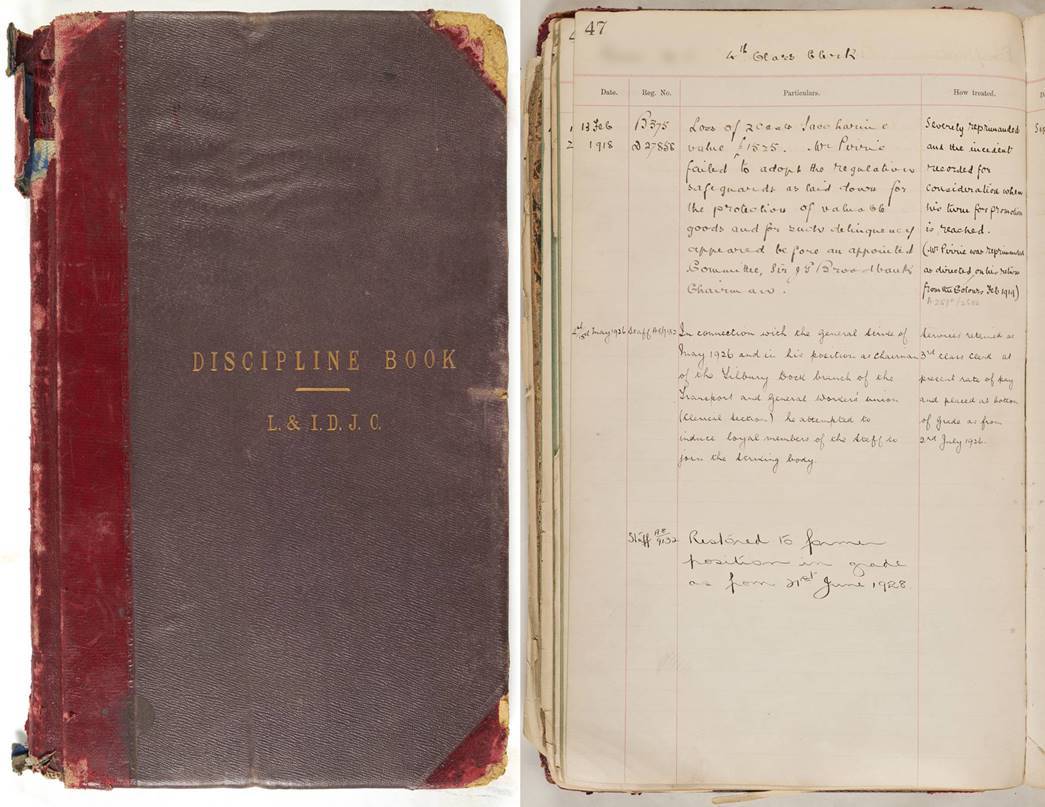

The Port of London Authority’s Discipline Books logged transgressions and sanctions within London’s docks — from pilfered wine to missing work to watch a football match! While these books do record some serious crimes, it seems the dominant sense is of human frailty, rather than malice.

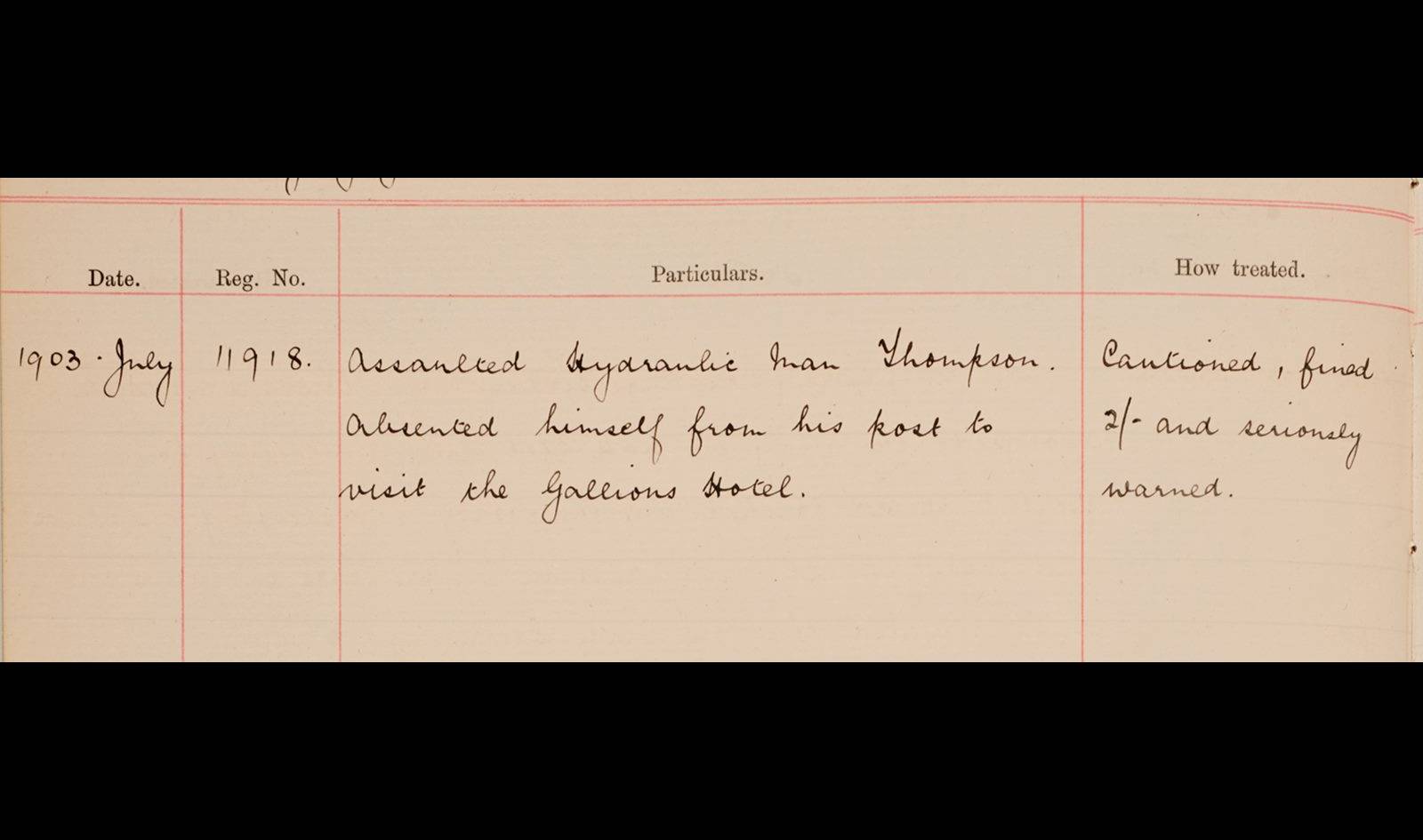

In the summer of 1949, a dockworker at the Port of London appeared in front of his employers on a charge of “being in possession of a rubber tube”. The incident was deemed serious enough to be recorded in the Port of London Authority’s (PLA) Discipline Book — a hand-written ledger which logged transgressions and sanctions. A further entry clarifies why it was considered an offence:

“Being found with a rubber tube for the purpose of unlawfully obtaining wine from a cask.”

Put simply, rubber tubes indicated that a worker had come prepared to siphon off alcohol from the wine and spirits warehouses at the London docks. The PLA police and managers were familiar with this practice and these entries were the first step in the disciplinary process.

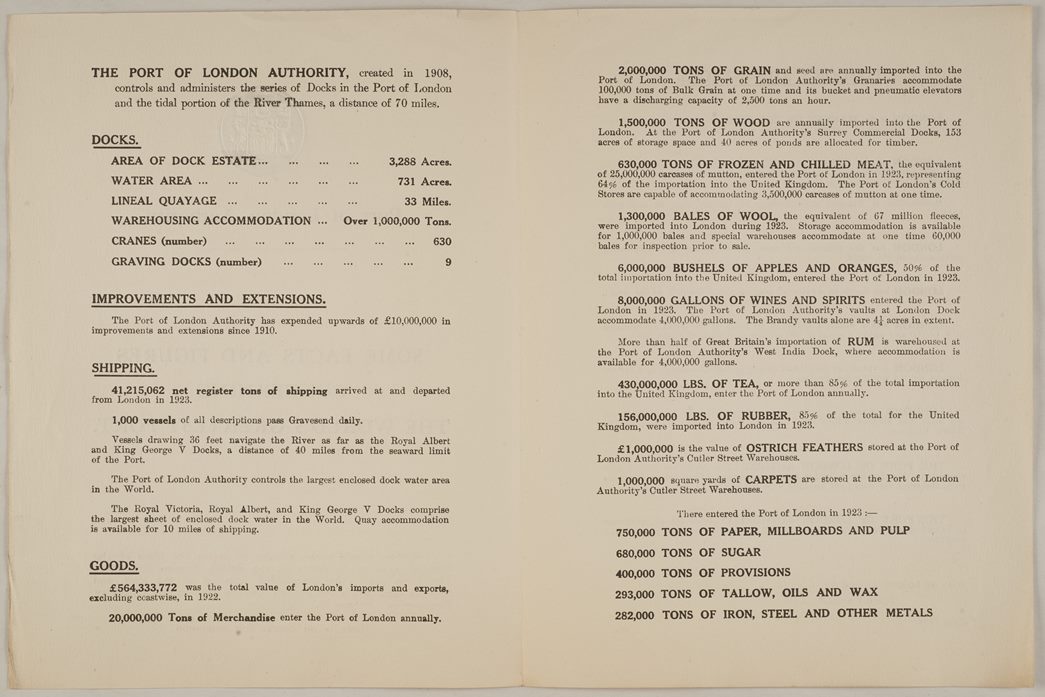

The PLA Discipline Books offer a unique insight into the self-declared ‘World’s Greatest Port’ and the network of warehouses, railways, canteens, offices, wharves, locks and vessels, which employed so many men and women in so many different roles. By their nature they capture failings rather than achievements, but in so doing they paint a very human picture of frailty, humour, insubordination, riotous behaviour and political awareness.

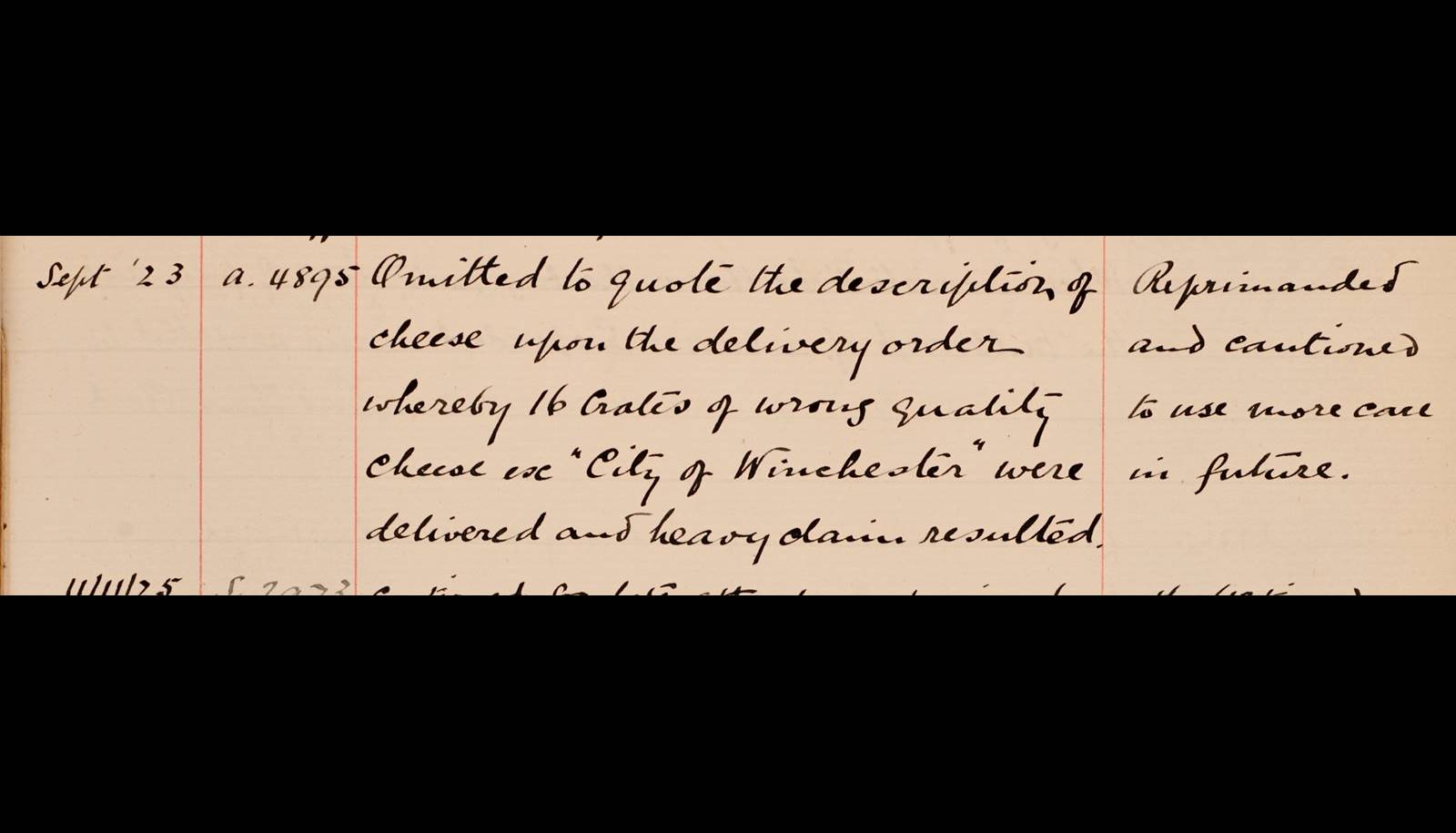

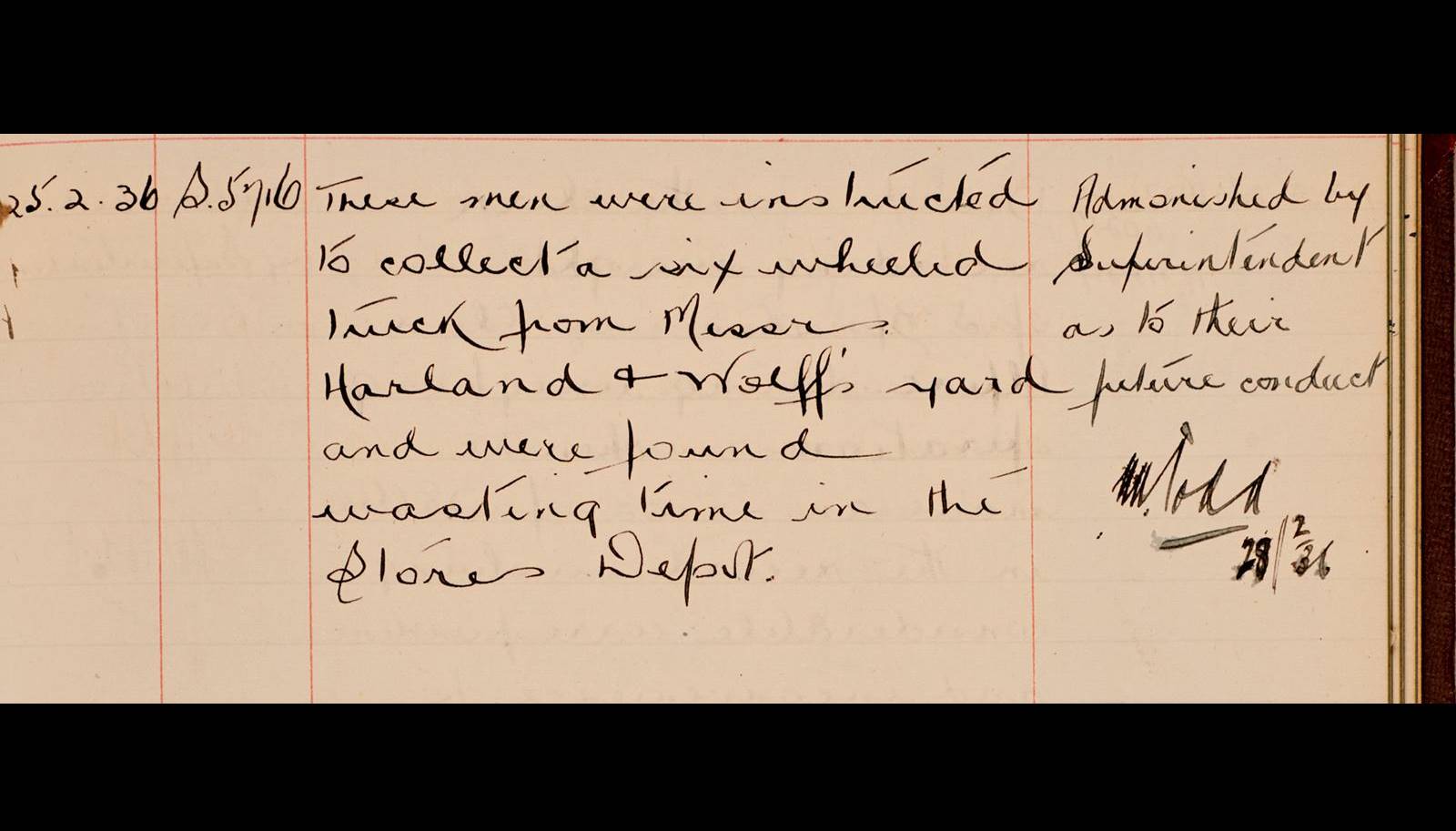

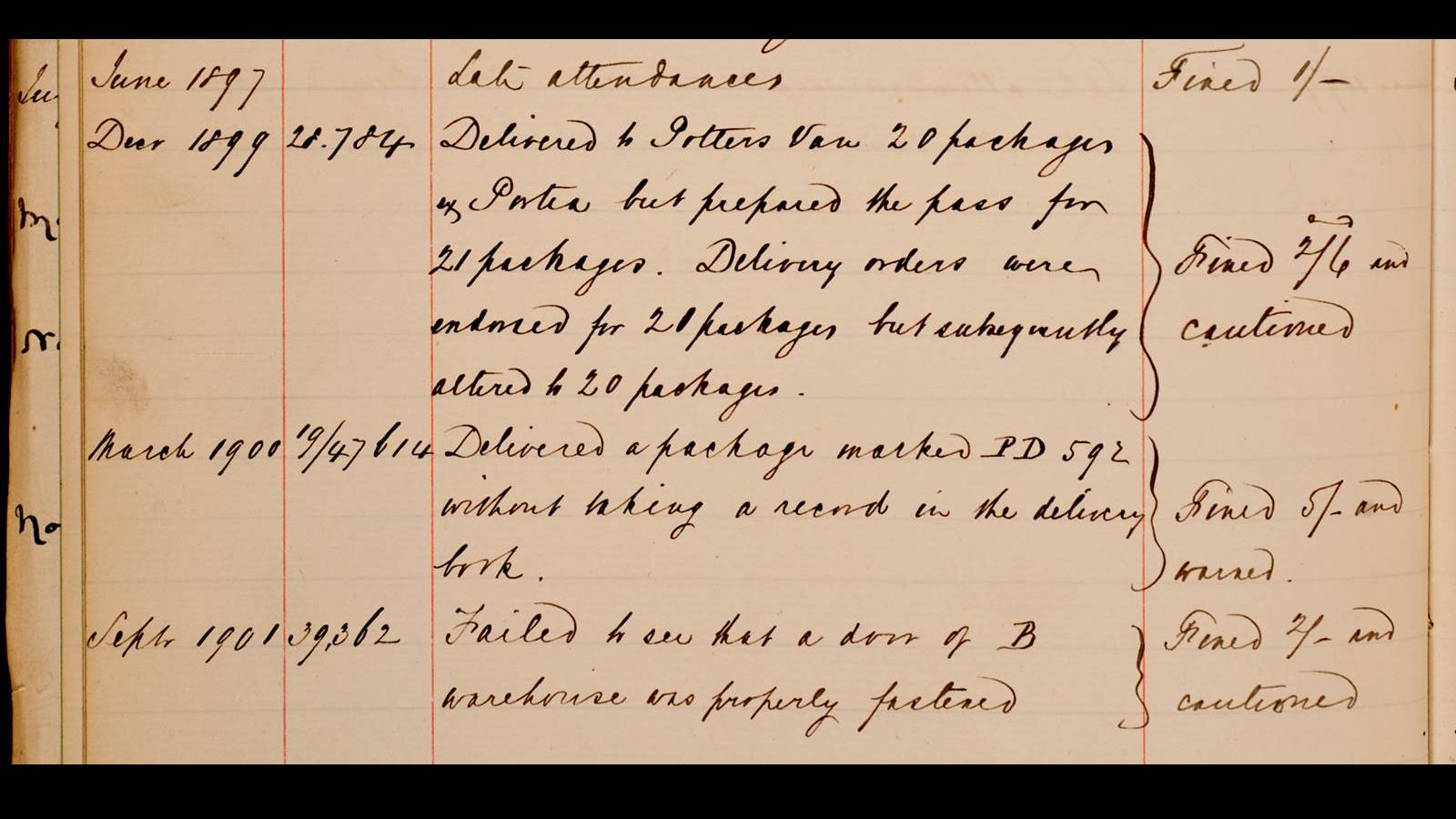

Mark your offence

Unsurprisingly, many of the offences reflect PLA’s overriding concern with operational and security issues. Weighing and labelling errors cost the PLA money through claims and usually earned the transgressor a caution, sometimes a docking of pay for repeat offenders. One employee was written up for failing to respond to letters from Selfridge’s department store in Oxford Street. The frequent reference to doors, gates and hatchways being left unsecured clearly illustrates that the security of premises and goods was of paramount importance to the Authority. Likewise, smoking on site or leaving naked flames unattended were disciplinary offences.

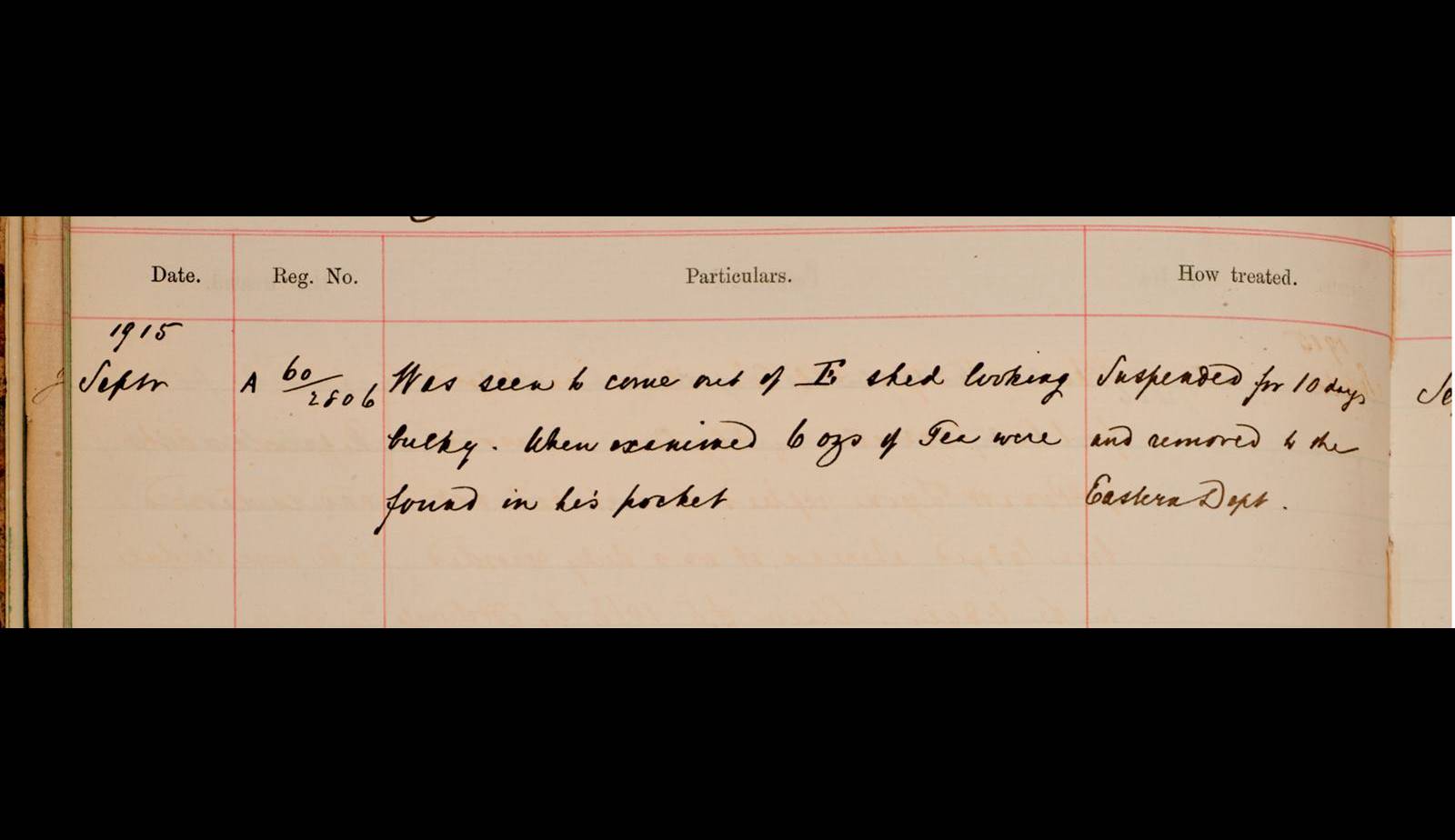

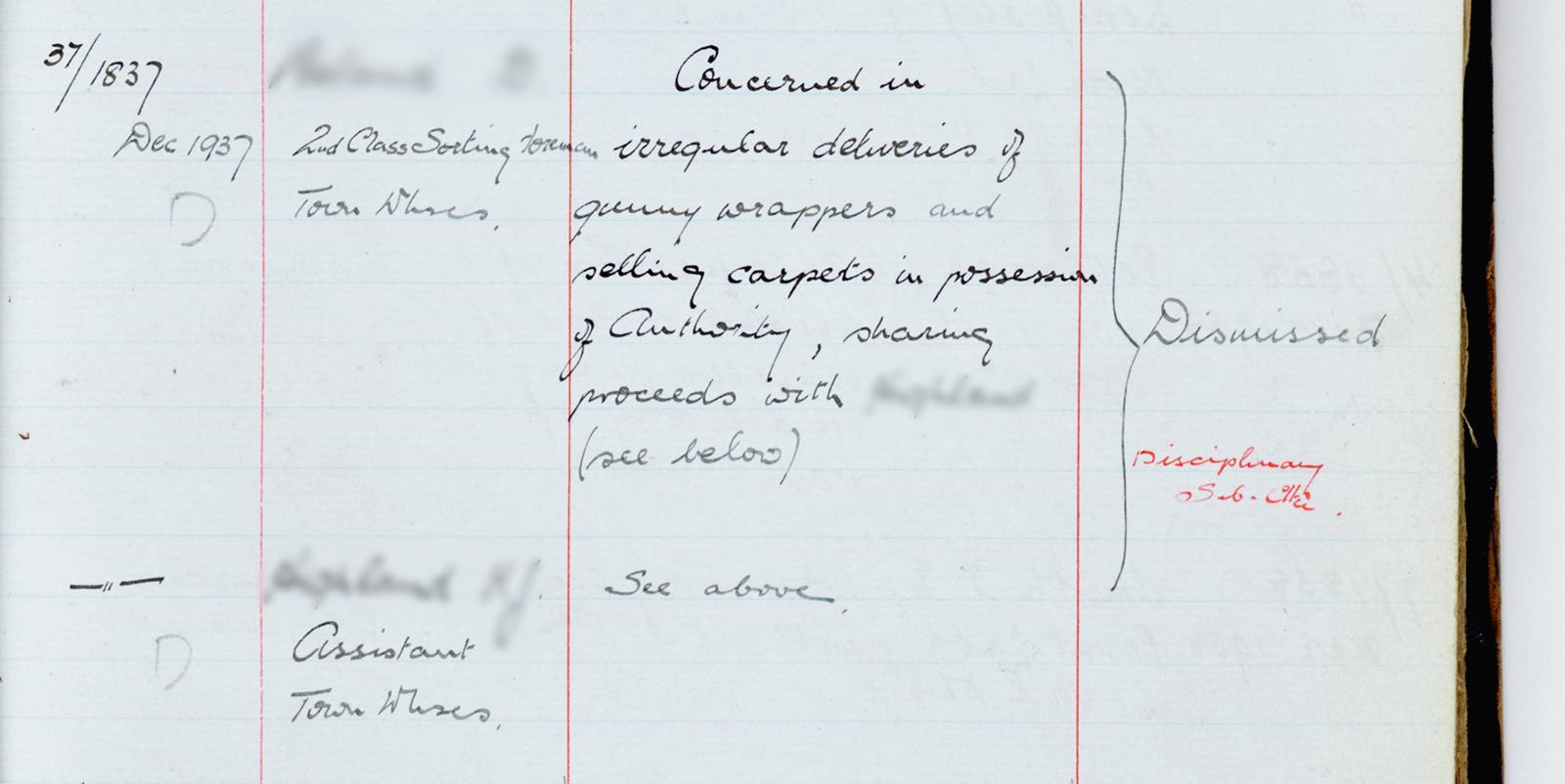

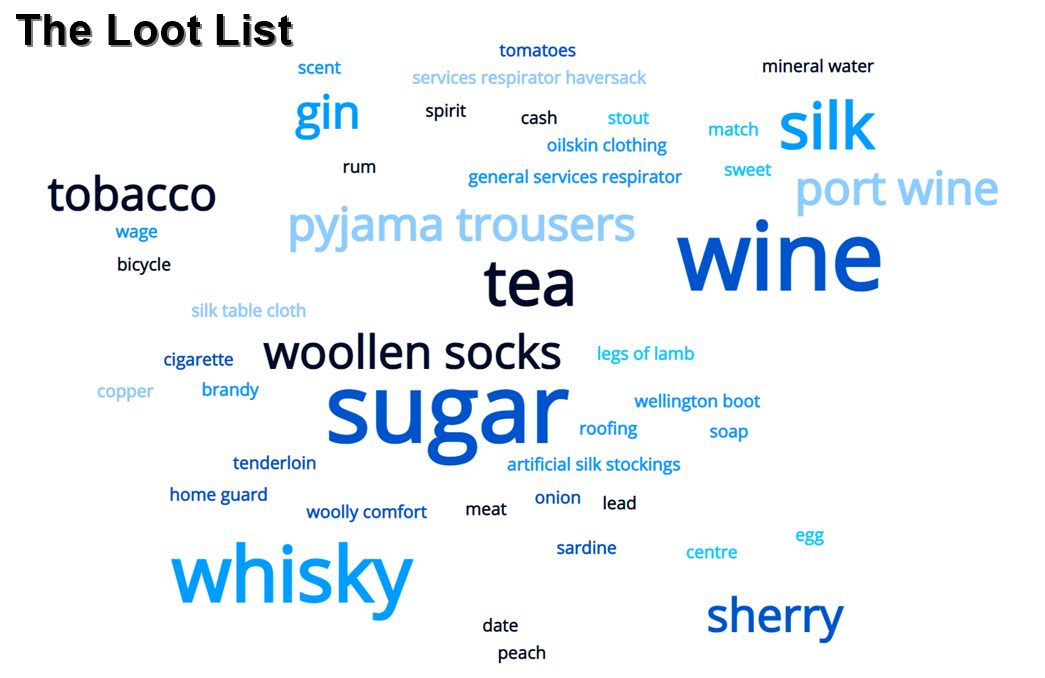

Another key area of concern was theft, but there is an interesting shift in the number of recorded incidents through the first decades of the 20th century and the period following the introduction of rationing in the Second World War. In 1937, a mere three cases of “pilferage” were reported: muscatels and almonds, tinned salmon and carpets.

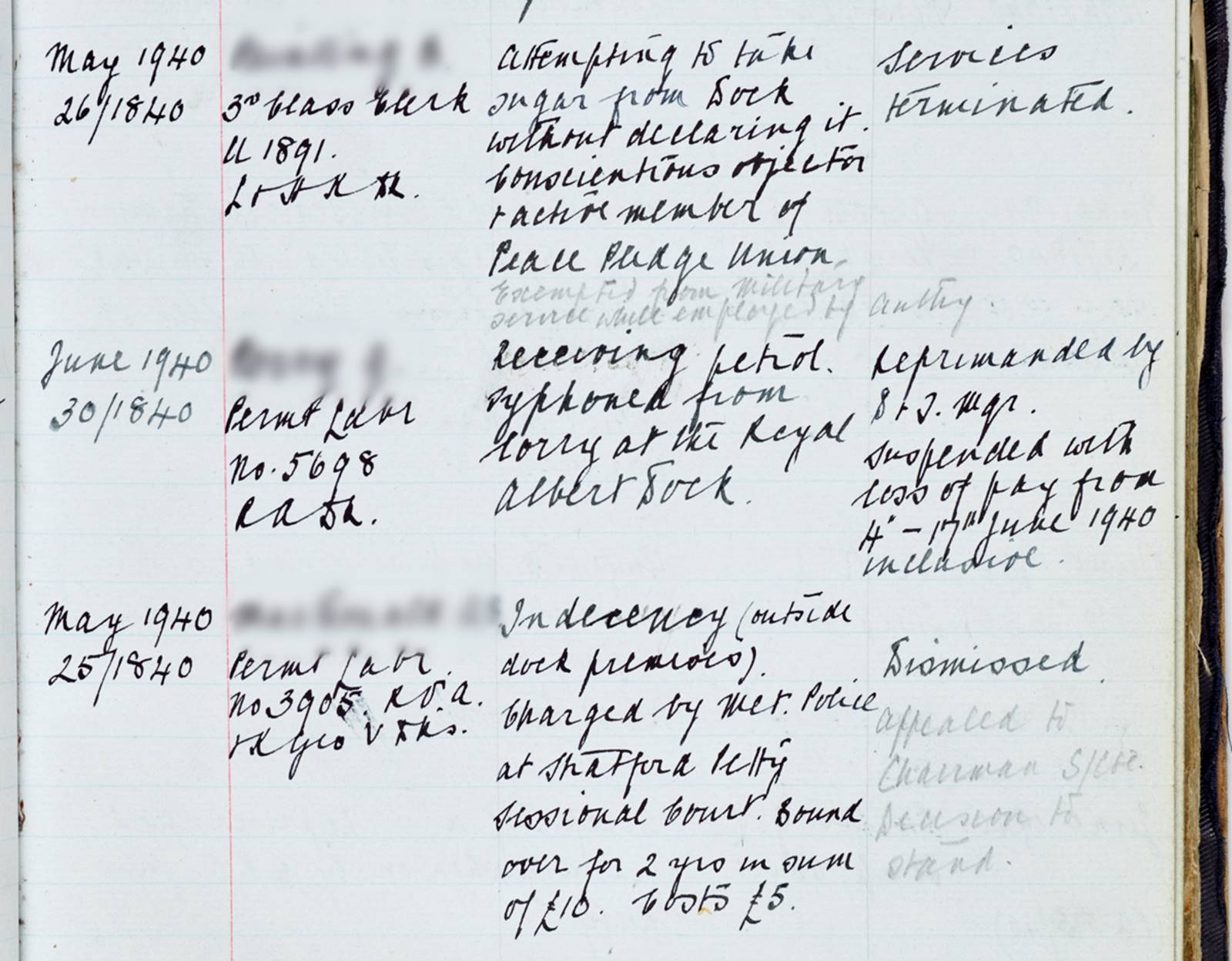

By contrast, in 1941, 50 incidents were recorded! Not only does this dramatic rise reflect the relative shortages in daily wartime life but they also provide an interesting perspective on the range of goods which were passing through London’s docks during and in spite of the Second World War.

A snapshot of stolen goods which featured in the discipline books from 1941. Click here for a more detailed list.

Other entries in the Discipline Books conjure up the atmosphere of the wartime docks. Two men, “whilst in Home Guard uniform and coming off duty [were] found in possession of tins of chopped ham and pork”. Five others were found playing cards in an air raid shelter. And the presence of the US Army is revealed by the fact that the US military stores and provisions were a clear target for appropriation.

The ones in times of war

Dockers unload lamb imported from New Zealand. (©Henry Grant Collection/Museum of London; ID no.: 004579)

Wartime also saw a rise in the number of entries relating to political transgressions. This may reflect anxiety and concerns about security. After all, the docks were of vital importance to the war effort and to the day-to-day survival of the whole nation. One entry relates to an ambulance driver whose services were terminated with a week’s pay and whose offence is starkly expressed: “Fascist”.

In the same year, another ambulance driver was dismissed for, “…unsatisfactory conduct and ‘communistic tendencies’”. Unfortunately, there is no further contextual detail, so the circumstances are tantalisingly unclear.

During the Second World War, PLA staff were regarded as essential workers, so were exempt from active service. Although many chose to join up anyway, the port was a place where some of those opposed to fighting felt they might be able to follow their conscience. But it was not always that simple. Two workers are recorded in the Discipline Books as conscientious objectors and members of the Peace Pledge Union. Both were dismissed. Others were written up for refusing to carry arms or work with war material.

The ones that make you chuckle

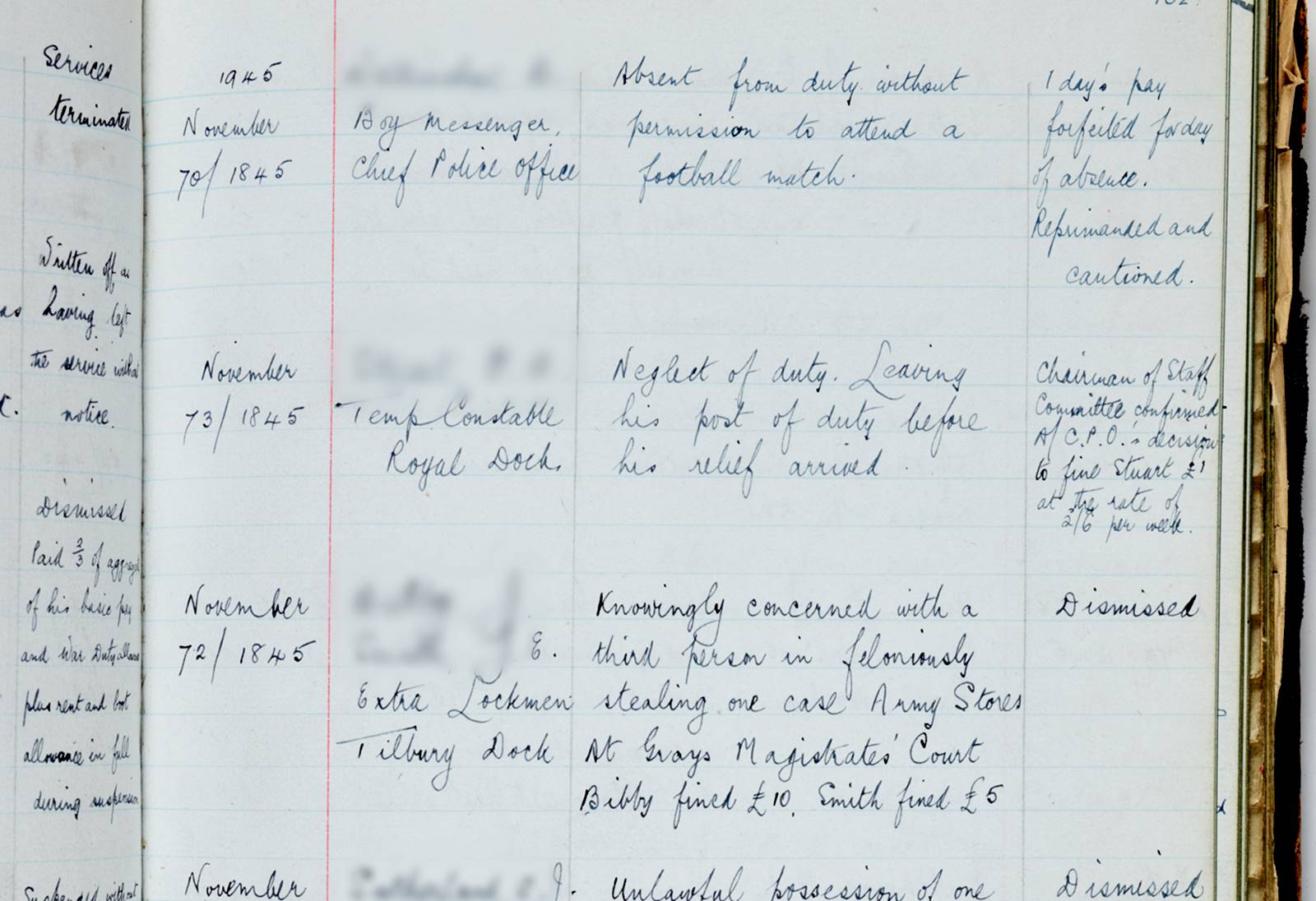

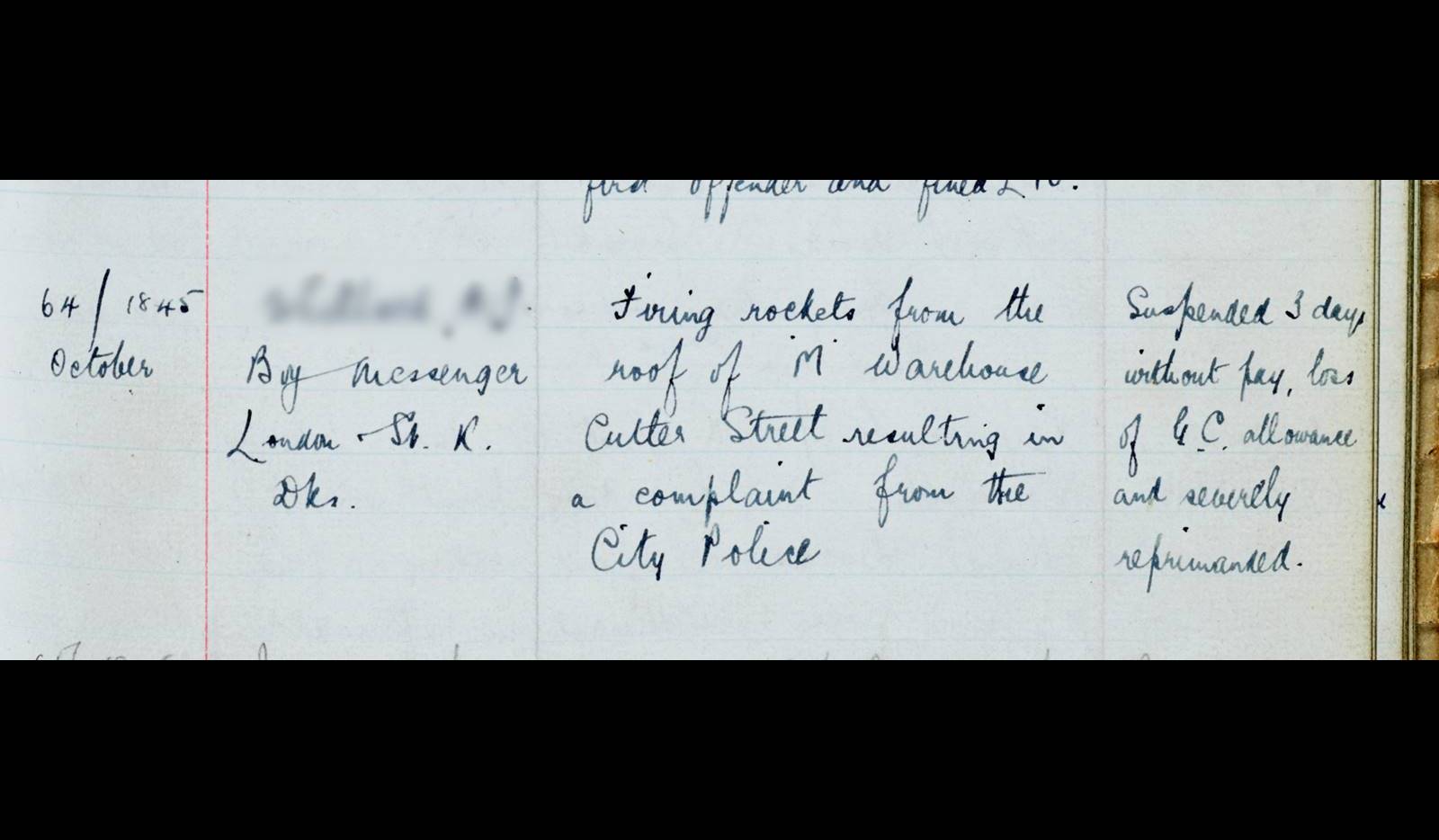

Some of the more entertaining Discipline Book entries refer to the teenage boys who were employed as messengers and labourers. One lad was caught, “…firing rockets from the roof of M Warehouse, Cutler Street, resulting in a complaint from the City Police”. Retribution was swift: three days without pay and a severe reprimand.

And several young opportunists had to be cautioned for, “…soliciting Christmas Boxes from City Firms to whom letters are delivered, after all boys had been warned against the practice”.

One simply absented himself, “…without permission to attend a football match”!

It is tempting to assume that the approach recorded in these pages represents a more arbitrary and unfair process than an employee might expect today. Certainly, most modern organisations, such as the PLA or the Museum of London, have formal policies ensuring that an alleged transgressor has rights and representation; such written policies may not have existed in the mid-20th century PLA. However, that does not mean that an unwritten process was not assumed and followed. There are entries that indicate that some individuals were found not to be at fault, so investigations clearly took place. To understand the process better and to judge how consistently it was applied would require further research.

However, there is one clear difference between then and now — and it is the issue of data protection. Under the General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR), organisations today may not retain records of disciplinary cases beyond a certain period. Digital records must be wiped and physical documents shredded. Our errors will not be recorded for posterity as our forebears are in these books.

While the Discipline Books do record some serious crimes, the dominant sense is of human frailty, rather than malice. And, sometimes, entries hint at troubled lives, such as the worker whose long list of absences ultimately resulted in the termination of his job. The last record for one simply reads, “No Pay. Domestic Trouble”.

It is a reminder that these were real people who lived complex and often difficult lives. Which of us would wish to be judged on our failings alone?!

Note: Due to the nature of the content and possibility of referring to living individuals, some of the discipline books within the collection are closed.