Drag performances are a much-overlooked aspect of the post-World War II period. These behind-the-scenes photographs from the 1950s by Alan Vines are a very rare testament of a form of entertainment that spans centuries.

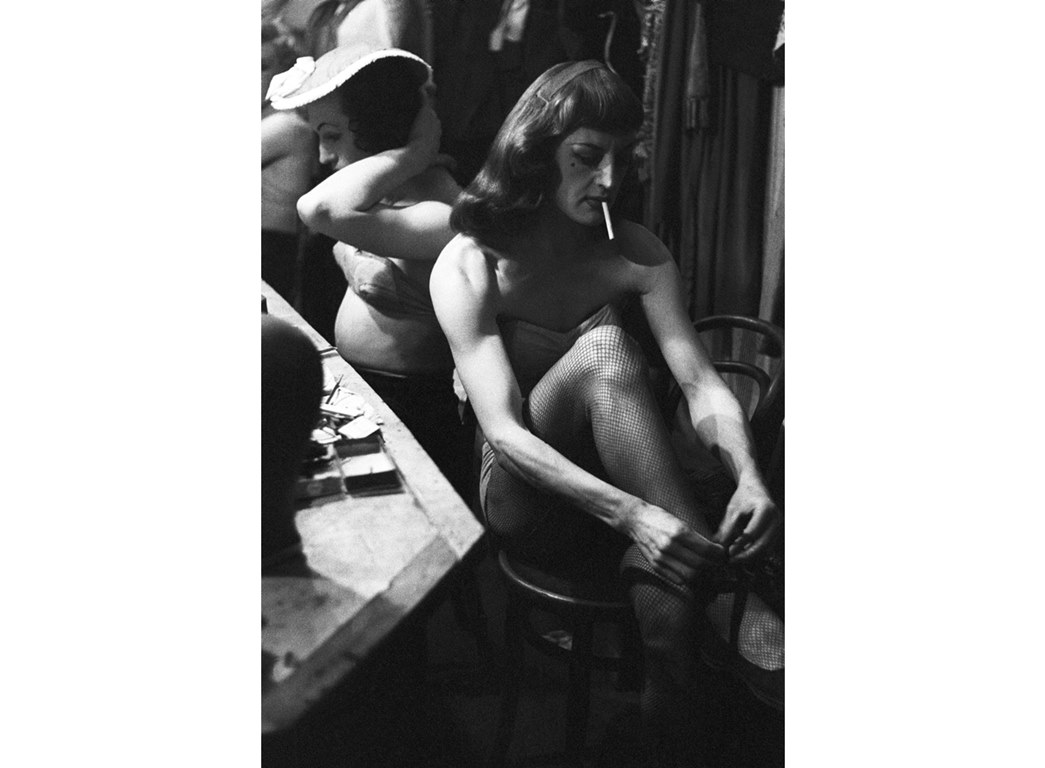

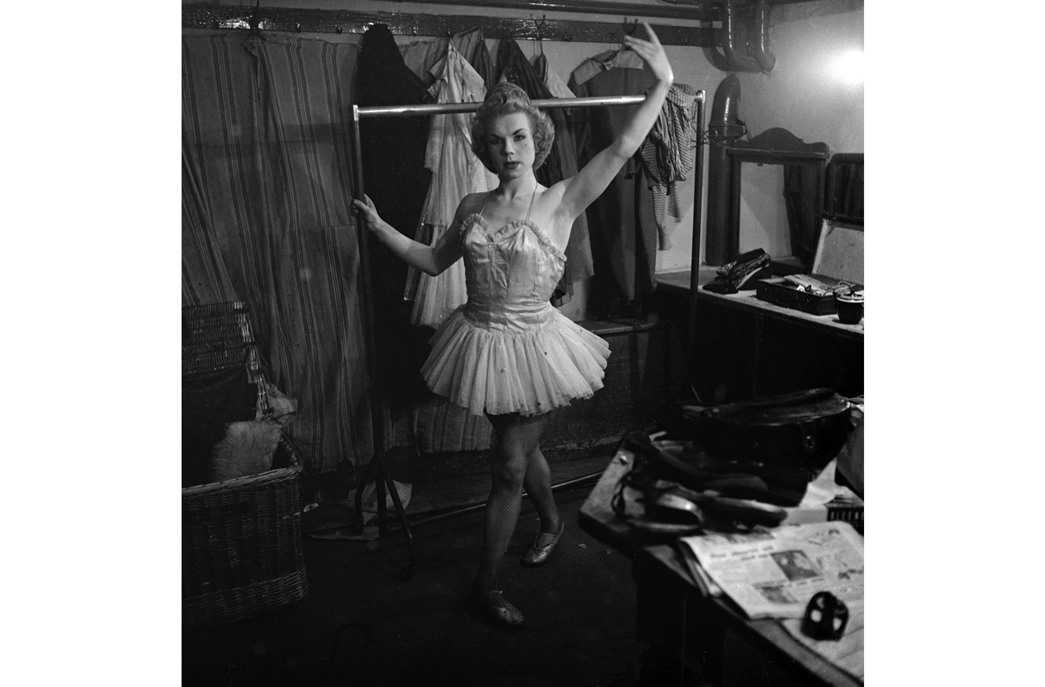

May, 1954. The cast members of This Was The Army prepare for their evening drag performance at Collins’ Music Hall in Islington, North London. That night will be one of their last shows — the revue will soon close after a successful nine-year run — but they probably don’t know that yet. Wigs, make-up, underwear, padding. Hats and hairspray, and cigarettes clenched between painted lips. In the dressing room with the actors is Alan Vines, a photographer working on a story for the Pictorial Press, who is hoping that his images will be published in Picture Post or Illustrated magazine. He snaps away while the all-male cast transform themselves into glamourous women, entertain an audience, run on and off stage, and head to the pub after the show.

This Was The Army was one of several drag revues touring Britain in the post-war period. Such shows were based on wartime army sketches in which servicemen played female roles to entertain the troops. Some of these sketches were turned into variety theatre after the war, and became a popular form of entertainment for audiences across the country. This Was The Army (1946) was staged by the married couple Jack Lewis, a comedian and ex-soldier, and Hazel Lewis, a former dancer. At nine years, it became one of the longest running shows, alongside Soldiers in Skirts (1945), and We Were In The Forces (1944), which gained so much attraction that it toured with multiple companies at once.

Drag: a popular form of entertainment

Terry Dorset, May 1954. (©Alan Vines / Topfoto)

Drag performances are a much-overlooked aspect of the post-World War II period, and photographs such as these by Alan Vines are very rare. Dr Jacob Bloomfield, an expert on drag history, points out that drag is not a phenomenon of the recent past, contrary to what we might think. Cross-dressing performance goes way back — to Shakespearian times for example, when male actors played female characters — and we know that the most common forms of contemporary drag (‘pantomime damery’ or glamour drag) have existed since at least the late 19th century. In fact, drag variety shows are an engrained part of British popular culture, Bloomfield emphasises, and some of Britain’s best-known stars of the post-war period were drag performers like Danny La Rue, who was perhaps even more popular than RuPaul is today.

It is therefore surprising that we are not familiar with more photographs of such shows. These beautiful black-and-white pictures by Vines only resurfaced in the archives of a Kent-based photo agency a few years ago, and some are now proudly held in our collection. We do not know much about Alan Vines or why he decided to photograph This Was The Army in 1954, save for a few biographical details: he shared a darkroom with renowned photographer Grace Robertson, was described as having a chaotic lifestyle, and gave up his photography career in the 1960s.

We do, however, know the names of the cast members pictured in these photographs — Pat Mason, Robert (Bobbie) Marlow, Peter Russell, Terry Dorset, Jimmy McGee, Jacky Guys and Sonny Dawkes. Although, the chorus girls would have changed regularly over the course of nine years. The original lead story that was written to accompany the photographs — but was never published — comments on the success of their female impersonation: “…although the war days and the war boys are things of the distant past, there is never any lack of recruits to the show in which, as the posters say, ‘Every Lady is a Perfect Gentleman’…. And it is very remarkable indeed. The illusion of femininity is very strong, even when you get the other side of the footlights.”

The creation of this “illusion of femininity” required great skill and effort. Drag revues were hard work. Performers would usually do two shows an evening, six days a week, and lived an itinerant lifestyle in exchange for a modest salary of £6-7 per week.

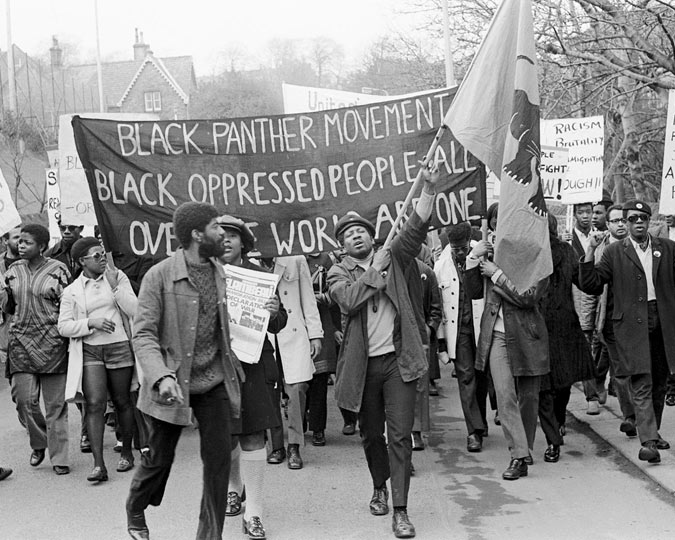

Queer history and identity

We now often associate historic drag with transgression, especially in light of the moral standards of the 1950s, but the reality was much more complicated than that. Drag revues were huge critical and commercial successes, and people from all walks of life and classes, across the country would come and see them. It was a national phenomenon and hundreds of thousands of people went to see the revues for a fun night out.

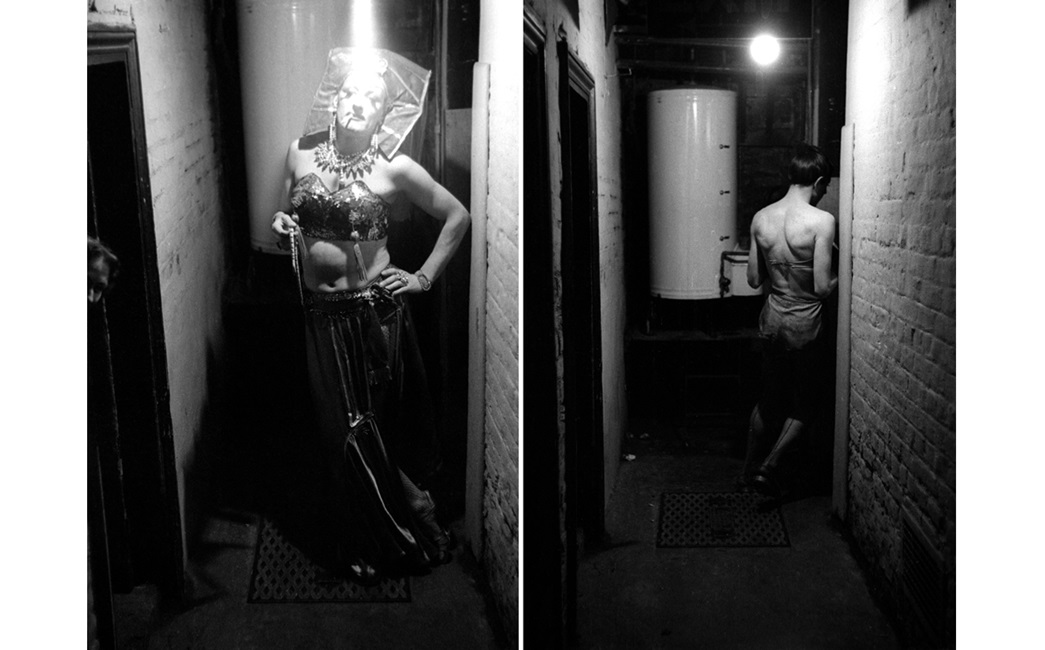

Audiences would have been both straight and queer, Dr Bloomfield points out, and there was little cultural consensus on the extent to which people explicitly associated drag with sexual immorality or homosexuality. The variety shows — with recurring acts like the mannequin parade, orientalist harem scenes, “dancing through the ages”, and celebrity impersonations — were performed with great skill. This explains in large part why they were so popular.

But homosexuality and queerness were certainly part of the scene. For some people, this acknowledgement caused discomfort, while others overlooked it or saw it as part of the appeal. ‘Stage door Johnnies’ were a common sight, lingering outside the music halls after the shows, eager to join the chorus or to run off with one of the performers. At times, the police would attend the shows to make sure the performance was following the licensed scripts, and to keep an eye on what the performers and ‘stage door Johnnies’ did afterwards.

Men in Frocks (1984), a book by Kris Kirk and Ed Heath that includes interviews with former post-war drag revue performers, notes that “for most of the queens, dragging was for fun, the camp and the giggle. But they began to realise that, even among their number, there were people who took it more seriously”. Cross-dressing might have been acceptable on the mainstream stage, but was much less so, off-stage. Some of the performers would pluck their eyebrows and grow their hair out to make the daily ritual of wigs and make-up easier. But at a time when men’s fashions and appearances were much more prescribed, it didn’t take much to turn heads with a look that deviated even slightly from the norm.

Drag as an expression of gender non-conformity was a motivation for some men to join the shows. The 1959 novel Chorus of Witches provides a fictionalised but insightful account of what it meant to be a member of the cast. One of the book’s main characters concedes: “It’s all right when you’re actually on the stage, knocking the audience cold with a bit of glitter and tit, but it’s a hell of a life tramping from town to town, spending every Sunday in a railway carriage and eating boiled cod in bed-sitting rooms practically every night of the week. And yet … we’d be far more miserable doing something else that we hated. At least for a few hours every day we can be ourselves and enjoy it.”

The tone of the shows was comedic, but the impersonation of feminine glamour was an earnest effort. We can see this reflected in Alan Vines’s photographs: casual and intimate shots that reveal an authenticity to the performers’ body language, upheld even when fastening shoes, or coming down the backstage alley. The images make us wonder: at a time when gender variance was little articulated, what would the inner lives and identities of these drag performers have been like? What did cross-dressing mean to them? And who might they have been today?

Candid photos of the performers having a drink at the bar of Collins’ Music Hall close the series. They can be seen talking to the editor of the Pictorial Press whilst still dressed in drag. The subtle gesture of a cigarette being lit or the fine hold of a sherry glass register as poignant visual clues to their interaction. Eventually, the editor never managed to get these photographs published (we can only guess why), but their recent rediscovery will ensure a second run in the footlights.

We are grateful for the valuable insights provided by Dr Jacob Bloomfield, whose anticipated book Drag: A British History will be published in 2023, and Flora Smith and John Balean of Topfoto agency, who hold the rights to Alan Vines’s photographs. This blog post is partly based on a workshop with them.