The Museum of London’s library has three music books owned by Emma Hamilton (1765-1815). The albums were donated to the London Museum in 1931 by Mr and Mrs Ernest Samuel Makower.

Mr Makower (1876-1946), a wealthy silk merchant, collector and philanthropist, had been a benefactor of the museum since 1924, when he first appeared with a parcel under his arm containing the vest King Charles I supposedly wore at his execution. After several other gifts and financial funding, in 1930 Mr Makower joined the museum’s Board of Trustees. In 1931, he donated several items to feature in a temporary display of London-made musical instruments. A review of the exhibition from The Times newspaper, 15 January 1932, mentions that among the instruments shown is “the guitar used by Emma Hamilton about 1800, which has been given to the Museum, with some of Emma’s music, by Mr. Ernest Makower.” The ‘music’ referenced here is a copy of Joseph Haydn’s oratorio The Creation and two volumes of bound pieces of music from between 1790 and 1807.

The entry in the museum’s accessions register mentions the items’ connections with Emma Hamilton but does not record ownership before they become part of the Makowers’ collection. It is reasonable to imagine however that this took place via an auction house sale.

As with many other famous personalities of the time, Emma Hamilton’s so called “relics” became collectable items and many often appeared in auction sales catalogues of the 19th and 20th centuries. Due to the increasing financial difficulties Emma experienced after Lord Nelson’s death, and in order to survive, she sold or had confiscated most of her possessions; with time, these became scattered all over national and international collections, both public and privately owned.

Joseph Haydn’s The Creation

The Creation (Die Schöpfung), Haydn’s choral masterpiece, was written between 1797 and 1798. The libretto follows the Judeo-Christian Creation story, with three parts covering the representation of chaos, the six days of creation and the story of Adam and Eve. It was first performed privately on April 1798 and in public on March 1799. With a combination of epic subject, cultural-historical ‘moment’ on the cusp between Enlightenment and Romanticism, it appealed to both high-minded and ordinary listeners.

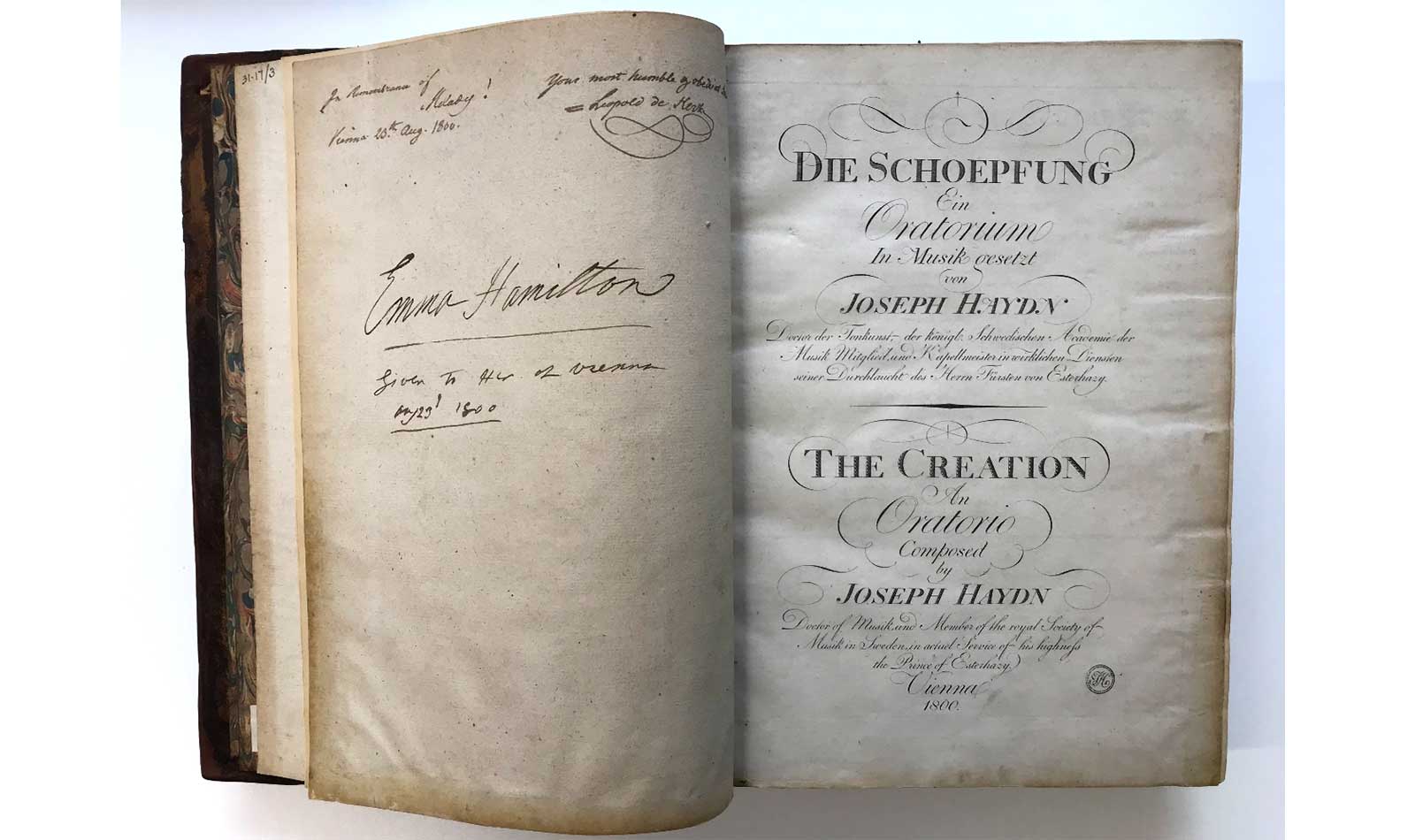

Haydn was aware of the achievements of his piece across Europe, so he spent months advertising an upcoming published edition: “The success which my Oratorio The Creation has been fortunate enough to enjoy … [has] induced me to arrange for its dissemination myself. Thus the work will appear … neatly and correctly engraved and printed on good paper, with German and English texts” (June 1799). The volume saw the light of day at the end of February 1800; as seen in the volume in our collection, copies from this edition had Haydn’s personal round stamp on the title page, the letters JH inside a circumference.

Emma’s personal copy has two handwritten inscriptions: at the top of the flyleaf (or binder’s blank), and in two blocks side by side, we read “In remembrance of Melady! Vienna 23th. Aug. 1800.” (original spelling kept), followed by “Your most humble [and] obedient servant Leopold de Herz”. In the centre of the page, with noticeable bigger lettering, it is written “Emma Hamilton / given to her [at?] Vienna, Aug 23d 1800”.

Lord Nelson’s travelling party

Portrait of Horatio Nelson, 1st Viscount Nelson, by Lemuel Francis Abbott, 1797

In the summer of 1800, two years after the famous Battle of the Nile and being recalled by the Admiralty, Lord Horatio Nelson was on his way back to Britain. Also travelling with his party were Sir William Hamilton, recently retired British ambassador in Naples, and his wife Emma. By the time the journey started in Palermo (Sicily) in early June, Lady Hamilton and Lord Nelson’s private (and very public) affair was well underway.

By August 18, the group had crossed Italy and reached Vienna; they would stay in Austria for a total of six weeks.

Through journals and letters, biographers have been able to trace the party’s daily activities with an astonishing level of detail. If we look at the days prior to Emma receiving Haydn’s copy of The Creation, we note that on August 21, Emma and Nelson met the Neapolitan royal princesses at the imperial palace. On August 22, the couple attended a comic performance at the Leopoldstadt Theatre. On August 23 however, the sources only mention Nelson’s meeting with the Emperor in order to discuss the next day’s grand reception.

The dedication in The Creation’s flyleaf implies that Emma met Leopold von Herz (or de Herz) on August 23, the context of their business however remains unknown. How and why did the presentation come about? Was this a personal gift from Leopold? The music book was available for purchase in the city at the time so von Herz could have acquired a copy, as a token of his appreciation towards the clients. The inscription after all shows an interesting degree of servitude for someone Leopold could only have met in the preceding five days.

There is no clear indication that the music book was a present sent by Haydn via von Herz, even though it is documented that occasionally he asked his publishers in Vienna (Artaria & Comp.) to send copies of his music to third parties. Even if Haydn became aware of von Herz acting as secretarial assistant (or solicitor) to the British while in Vienna, Leopold would have felt the need to record the correct source of the gift.

What do we know about Leopold von Herz (1767-1828)? O. E. Deutsch tells us that the von Herz were a Jewish family, one of the new acquaintances the party made in Vienna that summer. Leopold was a shareholder in his father’s wholesale business, a partner in the banking firm Offenheimer & Herz, and an amateur poet. In 1797, aged just 30, he became a nobleman due to his financial services to the crown. Leopold’s credentials probably preceded him and it could well be his services were recommended by the royal family to Nelson and the Hamiltons prior to their arrival in Vienna. The British party clearly trusted him during their stay: records of expenses to the firm Offenheimer & Herz show Nelson made good use of his services. In late September for example, von Herz assisted Nelson in paying the artist Heinrich Füger for three paintings ordered but not finished in time for their departure. Two weeks later, under Princess Esterházy’s request, von Herz forwarded a personal letter to Lady Hamilton, already in Dresden.

Whatever the context, origin and purpose of the gift, Emma clearly appreciated it. She made it hers with a far from discreet (and maybe even hurried) signature and date.

Haydn’s great admirer

On September 6, the Hamiltons arrived at Eisenstadt, Prince Nikolaus and Princess Maria Josepha Esterházy’s country estate, 40 miles from Vienna. Haydn, Court musician, had a small house near the palace where he spent the summer months. During their four days stay, the composer performed for his guests in several occasions, notably the unreleased Te deum for the Empress Marie Therese and his masterpiece Missa in angustiis (or Mass for troubled times). This would have been the first time that Nelson heard this work, renamed Nelsons mass by Haydn after the admiral’s death in 1805.

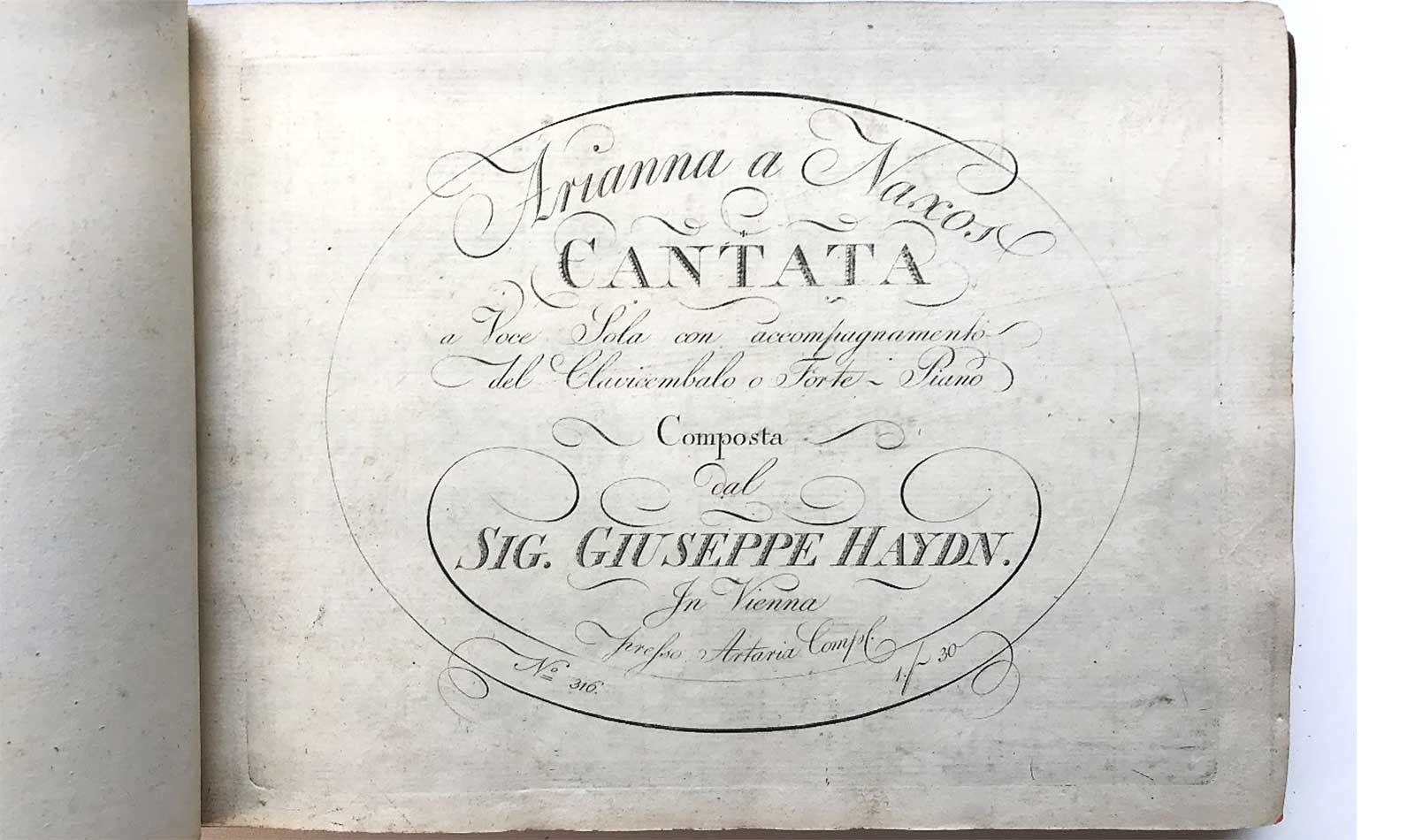

Three days before their arrival, Haydn learnt that “Mylady Hamilton” wished “to sing my cantata Ariadne in Naxos” so he requested his publishers to send the music sheets to Eisenstadt. Emma accompanied her idol at the piano, singing an aria from the piece. Her voice was described by a Hungarian reporter as clear and strong, “she filled the audience with such enthusiasm that they almost became ecstatic”.

Correspondence by guests at the estate shine a contradictory light on the bond that developed between Haydn and Lady Hamilton. While British guests implied Emma ignored Haydn in favour of playing cards, the composer’s friend and biographer Georg August Griesinger tells that Haydn had found in Emma “a great admirer. She paid a visit to Esterházy’s estates ... but was little concerned with its splendours, and for two days she never left Haydn's side”.

It is agreed that at some point during their stay, Haydn presented Emma with two manuscripts of his songs. Notes by Emma’s hand on them record the date of the gift, 9 September 1800. One of Emma’s music books in the Museum of London’s however includes what could be an additional souvenir from the encounter: a copy of the score to the above-mentioned Ariadne in Naxos, published in Vienna by Artaria & Comp.

Emma Hamilton

Emma Hamilton in an attitude towards a mimosa plant, causing it to demonstrate sensibility. Stipple engraving by R. Earlom, 1789, after G. Romney. © Wellcome Collection

Joseph Haydn and Lady Hamilton would perform together once more before the party’s departure from Austria on September 26. As requested by Emma during their visit, Haydn had set Cornelia Knight’s ode The Battle of the Nile (1798) to music. After a dinner at their Viennese inn, Haydn presented Nelson with the new cantata, accompanied, as one would expect, by Emma’s singing.

The British party continued their journey back to London, where they arrived on November 8 or 9. Soon after, the Hamiltons dined with Lord and Lady Nelson. This was the first time that Emma and Fanny had met in person and emotions were on show. Lady Nelson was cold and stiff with nerves; she had just discovered what everyone but herself must have known: Lady Hamilton was seven months pregnant - with Lord Nelson’s child.

Emma Hamilton had the most remarkable life, one where music was a constant feature. From her music books we assemble numerous stories, of the woman behind the myth, of the men in her life, and of the historical events that caused her rise and downfall.