From the first recorded execution at Tyburn in 1196 to the last public execution at Newgate in 1868, it’s said that London’s courts condemned more people to die than those in the rest of the country. Here are six facts that you might not have known about from those 700 years.

1. In central London, you’re always 5km from a known execution site

Until about the mid-19th century, public execution was the dominant form of punishment for most crimes in England. The authorities wanted to create a spectacle to demonstrate the power of the Crown, the State and Church over its subjects, and so, the process and consequences of the death penalty were made highly visible in London. Those living south of the river could see executions at the Horsemonger Lane Gaol in present-day Newington Gardens. At various points in London’s history, heretics were burned at Smithfield, traitors beheaded on Tower Hill and pirates hanged at Execution Dock near Wapping. Special gallows were erected at public spaces where rebels and traitors could be drawn, hung and quartered, while murderers and other infamous criminals were often executed on temporary scaffolds near the sites of their crime. In this article, which maps London’s execution landscape, we see how in central London, you’re never more than 5km from a known execution site, and in the City of London’s Square Mile, you are always within 500 metres of a place where the gallows once stood!

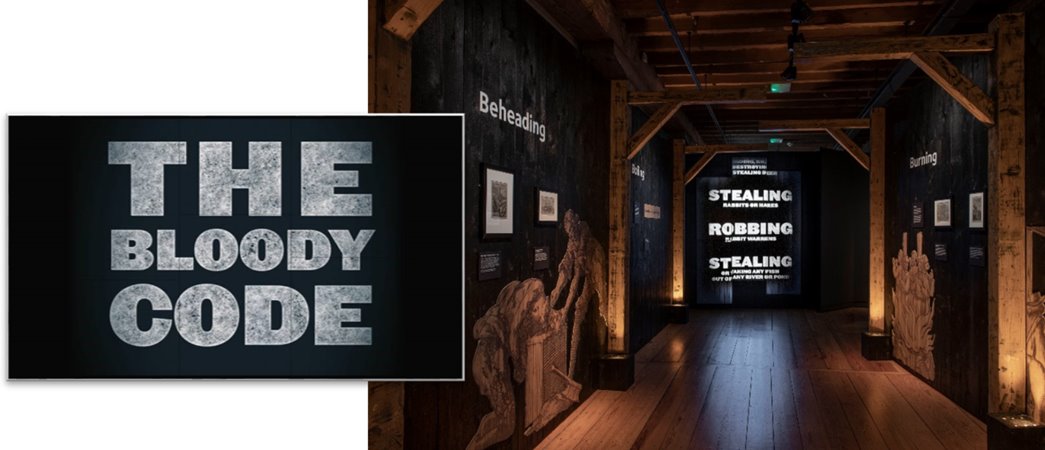

2. The ‘Bloody Code’: in 1723–1820, 220 crimes were punishable by death

In 1723, an act was passed which greatly expanded the number of crimes for which an individual could be executed — called The Black Act. More crimes were added over the years, and this list of crimes became known as the ‘Bloody Code’. The list included some familiar crimes such as treason, murder, rape, counterfeiting money, to more obscure ones such as stealing cloth from the rack, maliciously cutting down trees in a garden, cutting hop bines, and cutting and destroying wool, silk, linen or cotton. In all, there were over 220 crimes in Britain that could attract a death sentence. Soon after, there began a steady demand for reforms, as Chair of the Amnesty Anti-death Penalty Project Paul Bridges recounts in his article.

3. It was illegal to ‘speak, preach or write against’ King Charles I’s execution

The first and last state execution of a monarch in England’s history — the beheading of King Charles I for treason — had the public divided. The choice of the opulent Banqueting House as the execution venue was hugely symbolic, and strategic. While the state wanted his execution to be significant, the location would mean that the crowd could not be too large and the chance of rioting were lessened. The state did not want Charles I to be seen as a martyr, so it was made illegal to ‘speak, preach or write against’ King Charles I’s execution. In fact, a German print showing King Charles I’s execution — in the museum’s collection — would have been illegal in England at the time as it shows a woman fainting and other people crying. The museum also has a finely knitted silk undervest that was allegedly worn by him at the time of the execution. Read more about the vest and other Charles I relics here.

4. Guy Fawkes actually managed to avoid execution…

Actor Mr O. Smith as Guy Fawkes, print, 1829-1845

Uncoloured theatrical souvenir portrait plate printed with an engraving of the actor Mr O. Smith in the role of Guy Fawkes. Such portraits would have been sold as theatrical souvenirs for colouring and tinselling at home. (ID no.: 99.132/740)

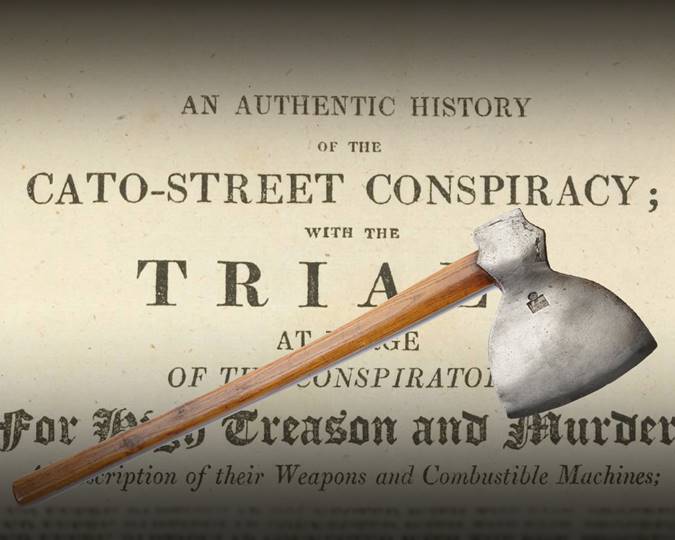

…by jumping from the gallows and breaking his neck! Yes, that’s right. Guy Fawkes is a prominent figure from the famous Gunpowder Plot, whose image has transformed from a rebel during the 17th and 18th centuries to, more recently, a revolutionary. Fawkes and his fellow conspirators had attempted to blow up Parliament on 5 November 1605, for which they were condemned to being ‘drawn, hanged and quartered’ — the ancient punishment for treason. This meant, the conspirators were dragged through the streets to the execution site, where they were hanged but cut down while still conscious. They were then castrated, disembowelled and their bodies quartered. Not many know, that on the second day of the executions, two men, including Guy Fawkes, jumped from the gallows to avoid the worst part of the punishment. Only Fawkes succeeded in breaking his neck. His body was then disembowelled and quartered.

Fawkes wasn’t the only one trying to avoid such a fate. In fact, some letters in the museum’s collection indicate that condemned prisoners often tried to cheat the gallows and avoid public punishment in front of a mass crowd by taking poison in the form of prussic acid the night before their execution.

5. Death masks of executed murderers were made for research!

Well, as research for the pseudo-science of phrenology, anyway. Practitioners of phrenology sought to determine human characteristics by analysing the shape and size of the head with reference to a phrenology bust. The death masks show the facial expression of the person immediately after their death, which was why it was important to make them quickly, so that the features did not become distorted. The theory was originally developed by the Viennese physician Franz Josef Gall in the late 18th century. He examined the brain of murderers after executions and claimed the area above their ears was larger than normal. He labelled it the “murder organ” or “organ of destructiveness”. Phrenology was subsequently discredited as false and racist.

6. Boys thieved to buy tickets to a play on the thief Jack Sheppard

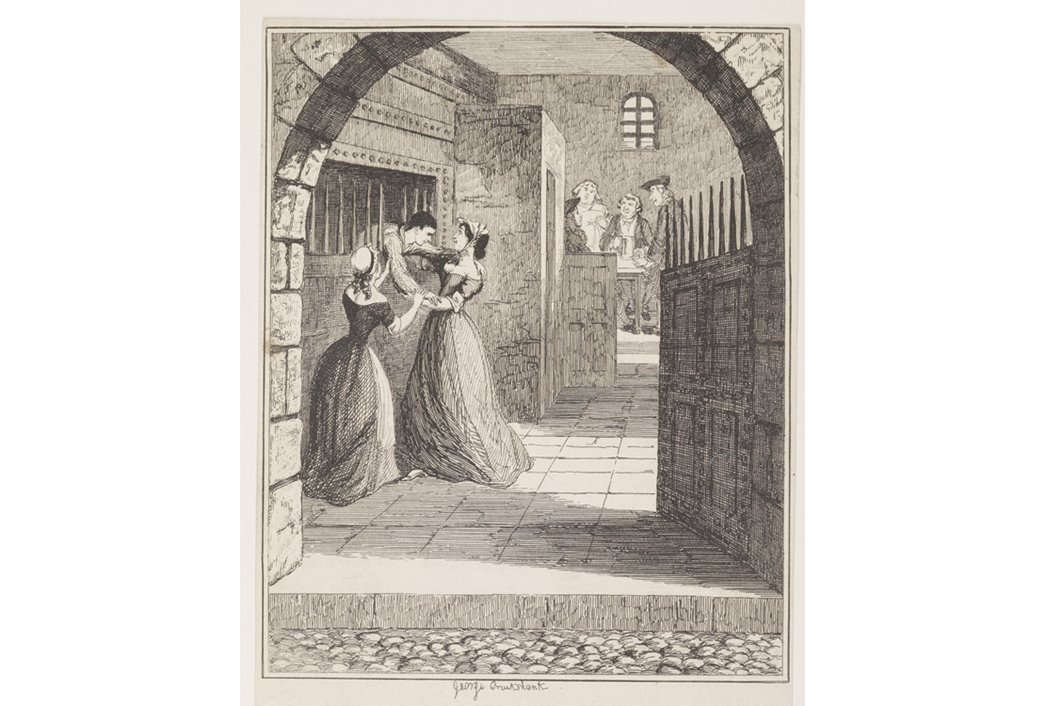

Jack Sheppard escaping from the condemned cell, etching, 1839

Jack Sheppard is a novel by William Harrison Ainsworth, which was published in serial form in ‘Bentley's Miscellany’ from 1839-1840, with illustrations by George Cruikshank. (ID no.: 54.122/1m)

John ‘Jack’ Sheppard was one of London’s greatest criminal heroes. Notorious for escaping multiple times from Newgate, he became a symbol of freedom for London’s working classes — executed at age 22, in 1724. An apprentice carpenter, Jack fell into a life of thieving, reputably led astray by ‘bad company and lewd women’. Although eventually executed at Tyburn at the age of 22, his effrontery and skill in challenging authority ensured his story was recounted in popular books and plays for generations. In fact, in the 1850s, journalist and playwright Henry Mayhew discovered that chapbooks recounting Sheppard’s exploits were hugely popular in low lodging houses where they were read aloud to illiterate youths. He interviewed 13 boys who confessed to thieving in order to pay for a theatre ticket for the play about Jack Sheppard’s life!

This article contains edited excerpts from Executions: 700 years of public executions in London, written by Thomas Ardill, Meriel Jeater, Beverley Cook and edited by Jackie Keily.

Explore the Executions online audio tour, which tells the fascinating stories behind some of the objects in our exhibition. The tour is a story of the executed, the Londoners who witnessed their deaths and the impact of public executions on the capital’s landscape, economy and society.