Professor David Lambert of Warwick University, curator of our 2017 display 'Fighting for Empire', tell us the astonishing story of Samuel Hodge, the second black winner of the Victoria Cross.

The 2017 exhibition centred on a single huge painting, one of a series showing those who

were awarded a Victoria Cross - the highest award for bravery in the British armed

forces. The soldier in this painting was Samuel Hodge, an African-Caribbean

soldier fighting in one of the West India Regiments, who displayed

extraordinary courage in a battle in the Gambia, fighting for the British

Empire.

Professor Lambert, what was the inspiration for this display?

This display related to the wider research project at Warwick University, “Africa’s Sons Under Arms”, which explores the history of the West India Regiments. The story of these regiments and the men who fought in them tells us so much about the intertwined histories of the Caribbean, west Africa and Britain.

Many people have may heard of the British West Indies Regiment, which fought during the First World War. But the West India Regiments lasted for much longer and had a much stranger history. Their origins were rooted in the British slave trade, and they went on to fight for the British Empire across the world for over 120 years.

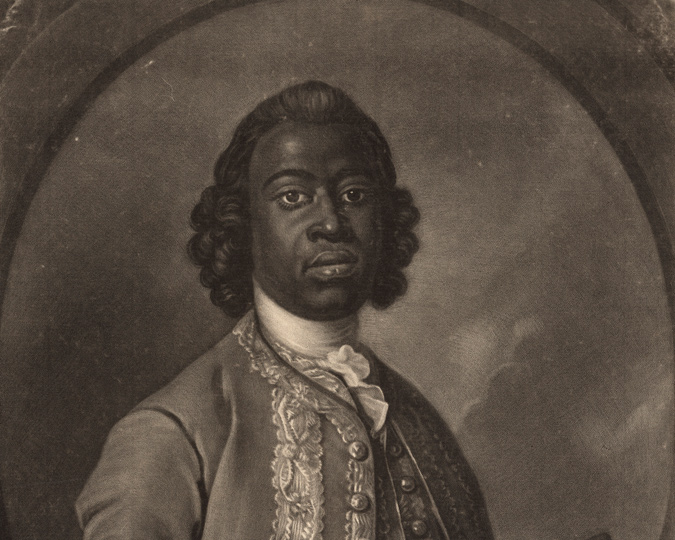

A Private of the 5th West India Regiment, 1812

J C Stadler. Courtesy of the Council of the National Army Museum, London

When and why were these regiments founded?

They were first raised in the British-controlled islands in the Caribbean in the 1790s, during the wars against Revolutionary and Napoleonic France. The Caribbean was a key colonial theatre in these conflicts. At one point, about a third of the British Army was stationed there, fighting over the tremendous wealth of the sugar plantations. These British troops suffered terribly from disease, as did all the Europeans in the Caribbean - dying from malaria, yellow fever, and dysentery.

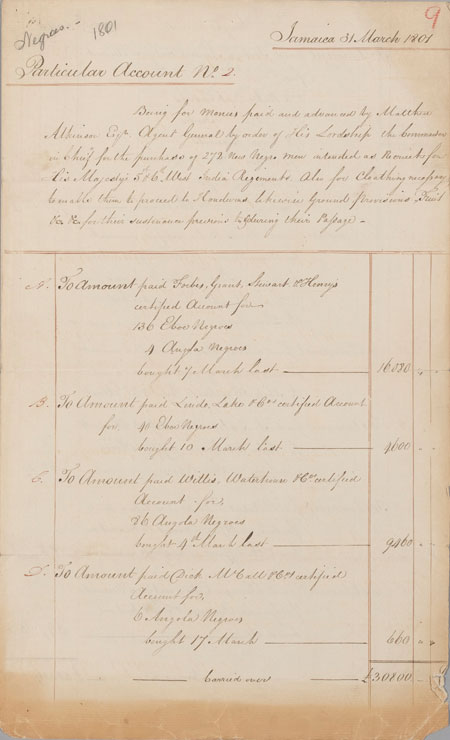

The British decided to recruit African men as soldiers, believing they would be more resistant to tropical diseases. And their source for these people was the trans-Atlantic slave trade. The British Army purchased enslaved Africans and forced them to fight as soldiers.

Was this unprecedented, to turn enslaved people into soldiers?

No, many of the British commanders in the Caribbean had fought in the American Revolutionary War just a few years before, where the British side had tried to recruit enslaved people to fight against the Patriots - the American revolutionaries. They had offered them freedom in exchange. However, there were lots of tensions between these army commanders and the local elites, the white slave-holding class, who wanted the black soldiers to be treated as slaves, and not as soldiers.

Account detailing the cost of buying and clothing 272 African slaves

The total cost show here was almost £33,000 - more than £1 million in today's money. © National Army Museum

Was it a better life to be a British soldier?

While the life of a redcoat in the 18th century army was harsh - poor conditions and brutal discipline - the treatment of enslaved people in the Caribbean was far worse. On some plantations, lifespan of enslaved people was only a few years, as slaveowners would literally work them to death. The British Army hoped to have a long-term source of soldiers: more than 13,000 enslaved African men and boys were bought at a cost of about £70 million in today’s money.

How long did they keep recruiting enslaved Africans?

The British Empire abolished the slave trade in 1807. As the date of that abolition got closer, you see a frenzy of slave buying from the British Army. But the end of the trans-Atlantic slave trade brought fresh opportunities to recruit African people. As the British began to enforce their ban, ships of the Royal Navy would stop and search vessels they suspected of transporting slaves. The people who they rescued from slavery weren’t transported back to their countries of origin - most were dumped in Sierra Leone. These ‘Liberated Africans’, far from home, were seen as a source of new soldiers. British Army recruiters - white officers with their black soldiers as interpreters - would sail to Sierra Leone and offer service in the West India Regiments.

Did these people understand what they were signing up for?

There’s plenty of evidence that they often didn’t. For instance, there was a mutiny in one of the West India Regiments in 1837 with those involved asserting they had been forced to become soldiers. They would be baptized in a mass ceremony, so that they were Christians in the eyes of the Army: only Christians could swear an oath of allegiance to the British monarch. These ‘West Indies’ troops were sent to fight across the British Empire, from the Americas to west Africa, including the Gambia.

Why were the British fighting in Gambia anyway?

British merchants had been trading in the area since the 1600s. The British claimed possession of the Gambia River in 1783, first to control the trade in enslaved people, then trying, after 1807, to stop it. Bathurst – now Banjul, capital of The Gambia - was established in 1816 as a Royal Navy base. In 1866, they were challenged by a local Muslim leader named Amer Faal, who was resisting British rule, and decided to respond with violence.

It was a classic punitive expedition of the Victorian period: a British force sailed up the River Gambia to get at Amer Faal’s fortress at Tubabakalong. After the bombardment failed, they had to assault the enemy stockade on foot. That’s where Samuel Hodge won his Victoria Cross.

Detail from The Capture of Tubabakalong, Gambia 1866

Showing Samuel Hodge (kneeling) and Colonel George D’Arcy. © Penlee House Gallery & Museum, Penzance.

What can you tell us about Samuel Hodge? That doesn’t sound like a very African name?

No, Hodge was from the Caribbean, specifically the island of Tortola, which is now part of the British Virgin Islands. He was born into freedom, around about 1840, but his parents would likely have been enslaved. Like many formerly enslaved people, Hodge took the surname of the British family who had owned his ancestors.

Hodge would have been about 26 at the time of the battle of Tubabakalong. He was one of fifteen soldiers who volunteered to breach the stockade wall so that the main British force could get in. The attack was led by Colonel George D’Arcy, the British commander, but most of the men were shot down by the fort’s defenders. Hodge himself was badly wounded, but he still hacked a hole in the stockade, and then spent the battle giving D’Arcy fresh rifles in the fierce fighting that followed.

Hodge was applauded as the bravest British soldier in the battle, and he received his Victoria Cross a year later. But shortly after, he died of his wounds from the battle. As a result, we know very little else about him. We don’t even know what he looked like - the artist who painted this portrait, Louis William Desanges, had never seen him. The only person who sat for this painting was D’Arcy, the British commander.

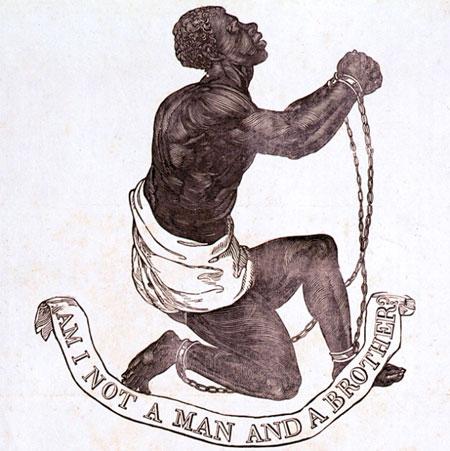

Am I Not a Man and a Brother?

Design of the medallion created as part of anti-slavery campaign by Wedgwood, 1787. Public domain.

Does that explain why Hodge, the hero, is kneeling?

It’s certainly a factor - you can see he’s passing a rifle to D’Arcy, presumably one he’s just picked up of the ground. But his pose also strongly recalls the famous anti-slavery design, “Am I Not a Man and a Brother?” by Josiah Wedgwood. Whether Desanges intended this similarity to a hugely popular image, it would have resonated for the painting’s audience. Hodge, the child of slaves, someone who is below D’Arcy in the Victorian racial and military hierarchy, is portrayed in a subservient and grateful fashion. It’s a reminder that even as the British Army employed black soldiers, they were not seen as equals.

In the British Virgin Islands, where Hodge is remembered as one of their most famous native sons, they produced a stamp with his image on it. He’s not kneeling in that image - he’s on his feet, breaking the stockade, and D’Arcy is nowhere to be seen. It is a much more positive and assertive image of a hero.

So the British Empire in Africa was partly forged by people of African descent?

Yes, and that is one of the things that we wanted the exhibition to explore. Not just in Africa: in 1816, West India Regiment soldiers were sent to fight 400 enslaved rebels in Barbados, who cheered when they saw black soldiers. As one of the white British officers said: "The insurgents did not think our men would fight against black men, but thank God they were deceived".

Perhaps it’s one of the reasons why this history is not well-known: these men who fought for empire do not fit comfortably into narratives of either British imperialism or African resistance. Do we celebrate these soldiers’ actions, given these included putting down slave rebellions and fighting Africans? It was part of the fascinating story on display in 'Fighting for Empire'.

Fighting for Empire closed in September 2018.