We explore the past and present of alternative currencies in London, and how they've been used to further economic and social changes in the city. This was part of our City Now City Future season, looking at how citizens around the world are improving their urban lives.

Trading in trust: local currencies

17th century trade tokens

Issued by Henry Brand's Cross Keys, John Sherwin's coffee house, the Golden Anchor, and bodice maker James Leech.

Trade token from the Turk's Head coffee shop, advertising its new address in Barbican, formerly in Pannyer Alley.

These tiny copper tokens- almost all less than two centimetres across- are some of the millions of trade tokens that became the currency of ordinary Londoners in the mid-17th century. Between about 1648 and 1673, almost no small-value coins were minted by the government.

Official change was in short supply and whilst the wealthy used credit, everybody else needed a way to do business. So traders pressed their own farthing or half-penny tokens to give as change.

Tokens could be spent locally, not just in the business of the person that issued them. Businesses accepted tokens issued by people they knew and trusted to honour its value.

The tokens on display in our 2018 (Un)common Currency exhibition were from Barbican Street, now Beech Street tunnel. It was a thriving community of tradesmen, particularly in new and second-hand clothing, with plentiful inns and coffee houses. Each token includes the names, initials and symbols of some of these business people – including bodice maker James Leech, meal man William Milton, and chandler Thomas Cooper. Robert Hayes cleverly used his token to advertise the new address of his Turk's Head coffee shop, after he had to move premises due to the Great Fire of London.

The Crown began to produce farthings again in 1672, and a proclamation banned the private issuing of trade tokens. But further proclamations issued in 1673 and 1674 suggest that they continued to circulate, showing that locally-made, reputation-backed currency served a valuable purpose in London's economy.

Proposed design for Kingston pound banknotes, 2016

A more recent example of a local currency is the Brixton Pound, which was also on display in (Un)Common Currency in 2018. The Brixton Pound (B£) was the first urban "complementary currency" in the UK, meant to be used alongside pounds sterling for local purchases, just as trade tokens were used alongside gold and silver coinage.

The Brixton Pound is designed to encourage local spending, and its vibrant series of notes celebrates the area’s people and places. The design of each note features inspirational Brixtonians past and present, from David Bowie to international basketball player Luol Deng. The backs reference the iconic Coldharbour Lane Barrier Block social housing, and local street art.

A similar local currency is the Kingston pound, a wholly digital alternative currency for the west London borough. They're one of 25 projects from across London featured in our City Now, City Future season. Each of them is a local initiative, business or charity working to improve the city and put power into the hands of Londoners.

Time is money

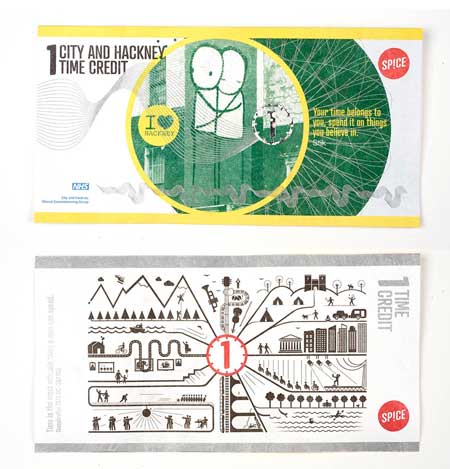

City and Hackney Time Credit

Created by Spice Innovations Ltd on behalf of NHS / City and Hackney Clinical Commissiong Group. ID no. 2017.46/1.

Some London alternative currencies choose not to replicate the standard units and values of the financial establishment. Instead, they seek to create a radically different unit of exchange, based on the one commodity that everyone has a limited amount of – time.

This rare note is worth one hour of somebody’s work. It comes from the first Equitable Labour Exchange, set up by the socialist Robert Owen just off Gray’s Inn Road on 17 September 1832. The principle was that goods were exchanged based on the number of labour hours that went into producing them rather than on their resale value. The exchange produced notes such as this one to help facilitate exchanges of products.

Branches followed in Blackfriars Road and Birmingham, and at their height goods with a value of 400,000 hours were deposited the Exchanges in just one week. However, the Exchanges proved short lived as the quality of goods dropped.

These modern Time Credit notes come from London-based volunteering schemes, run by the charity Spice. The idea is simple: those who give their time should be rewarded with time. By volunteering for a local good cause you earn credits to spend at one of their partners – from local businesses, leisure centres and cinemas to major visitor attractions. Each note is valued at an hour, and can be redeemed for an hour-long experience. The notes can also be given away as gifts for others to spend – creating a currency that can circulate. Homeless people in Hackney and recovering addicts from Haringey are some of the many people who have benefitted from this scheme.

From small change to social change

Creating your own money is a strong political statement, as well serving a practical purpose. Producing money implicitly challenges the financial establishment, suggesting that people have needs that cannot be met through the existing monetary system. It's no surprise that people seeking radical social change have embraced alternative currencies, both as a way of spreading their messages widely and of funding their movements.

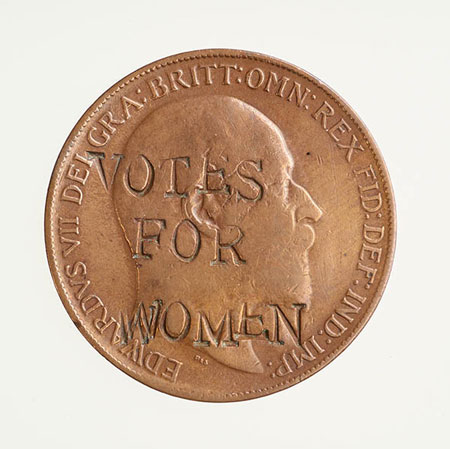

One penny coin stamped "Votes for Women" across the profile of King Edward VII, 1910

ID no. 63.44

There was another shortage of British coins in the 1790s, at the same time as the French Revolution was exciting London's radicals. Many political movements produced collectible coins and tokens, combining economic needs with their message of change.

This half-penny token uses Josiah Wedgwood’s image of the enslaved African kneeling in chains and was made to raise funds for the campaign to abolish slavery.

Other movements changed official currency rather than making their own. This 1910 one penny coin has ‘Votes for Women’ stamped on King Edward VII’s head. At this time women were denied the vote. Defacing a coin was a serious criminal offence, but low value pennies were rarely recalled by the bank. This coin could end up in the hands of any man or woman in the country – circulating its message widely. It was just one tactic used by Suffragettes to campaign for the vote.

Alternative currencies are more than just a curiousity or a way of spreading a message. The everyday economics of spending and earning money are so entwined with our lives that changing what we exchange can reshape the way we think and act. Londoners throughout history have used alternative currencies to try to change the city, and the world.

Our (Un)Common Currency display ended in January 2018.