Our London Nights exhibition included images from the Metropole series by Lewis Bush. He spoke to us about whether London's skyline is beautiful or repulsive, and where you should be in London at midnight.

The London Nights exhibition closed on 11 November 2018.

How did you become a photographer?

I grew up in London, studied history and then after that I worked for the United Nations HIV/AIDS taskforce as a researcher. Although this was a great experience, it also made me realise I didn’t really want to spend my career in an office so when I came back to the UK I decided to start taking photography more seriously. I did an MA at London College of Communication, where I now also teach, and after graduating it was just a slow path of working away on developing projects and finding my feet as a photographer. Through that process some of those early experiences have come back into my work: what I do now is underpinned by a lot of research into the subject that interests me, and often by an equal use of photographs and texts.

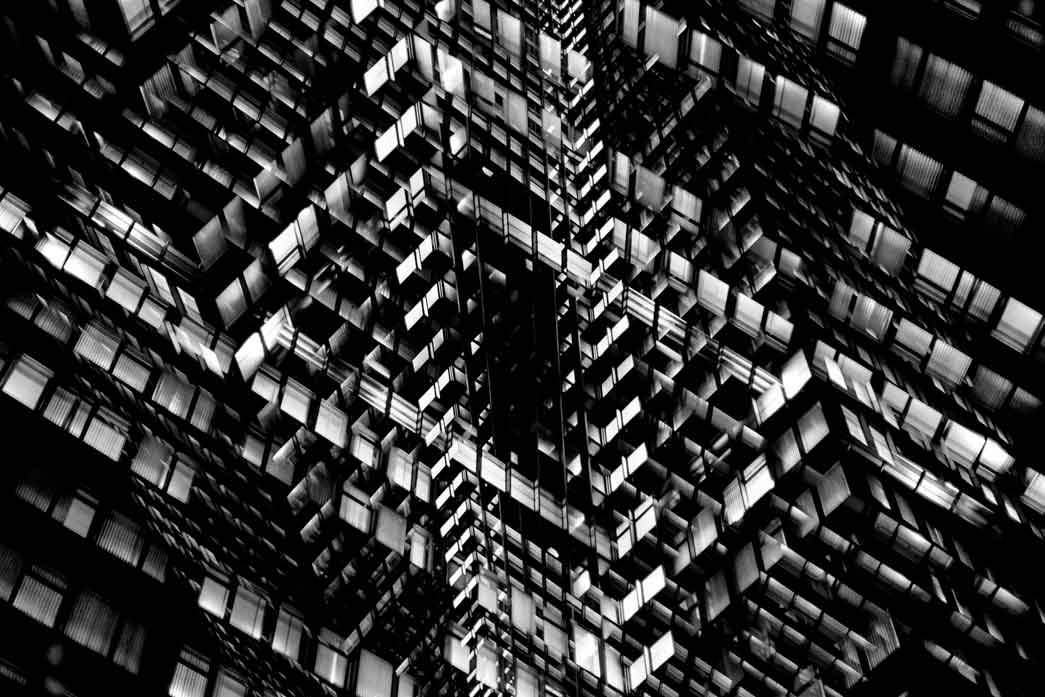

"Metropole tries to make viewers see these buildings as threatening, disorientating and alien"

London Nights includes work from your series Metropole - how would you describe it?

Metropole is an attempt to emulate my experience of feeling increasingly alienated from the city I grew up in. I’ve spent most of my life in London and when I was first becoming interested in photography I would spend hours wandering through the city, photographing it, in the process also becoming much better acquainted with its present and its past. Today I see much of what I love about the city being swept away by a huge glut of demolition and construction taking place under the guises of ‘development’ and ‘regeneration’, but which in my eyes are actually more a form of degeneration which is stripping away the essential character of London and forcing Londoners out of the city. This is in turn driven to a large degree by international flows of finance, and a class of developers and speculators who see London property and in particular housing as a financial asset rather than an essential human need.

My response was to walk the city by night, photographing these new constructions and attempting to make viewers see them as threatening, disorientating and alien in the way that I do. To heighten this sense of disorientation I double or triple expose each scene, layering buildings over buildings in order to create visually plausible but actually impossible structures. Visually Metropole is influenced by early cinema, particularly the city symphony genre which emerged in the early twentieth century and eulogised urban living. In my case what I am trying to produce is more of a requiem for a city lost to aggressive redevelopment. Aesthetically Metropole is also influenced by post-war Japanese photography, for example by Shomei Tomatsu and Hiroshi Hamaya, who in a different sense were witnessing and documenting the transformation of their society at the hands of an outside power.

"I’ve lost track of the number of times I’ve been threatened while working on Metropole"

What does London Nights mean to you? What do you think of when you think of the city after dark?

I think of a place where opportunities and threat are mixed together. Visually the city transforms itself at night, places which are familiar in daytime can take on an entirely different feel, and I find that exciting and challenging as a photographer. At the same time, it is inevitably tinged with a sense of risk- even in the rarefied atmosphere of the financial districts where I was often shooting for Metropole. This usually comes in the form of people involved in these redevelopments, who rarely take kindly to strange people photographing the inner workings of their buildings at night, all the moreso when I explain the project to them. I’ve lost track of the number of times I’ve been threatened while working on Metropole, with everything from legal action to hints of violence. Unfailing politeness combined with a robust knowledge of the law make for a good response in most of these cases, but these encounters still often left me wary of continuing to explore the largely deserted streets around these sites.

Metropole is obviously very focused on London’s architecture- what draws you to the city’s skyline?

I think I am less drawn to it than repulsed by it. The architecture of these high rises is a matter of aesthetics, and I appreciate that people will have different opinions about whether these towers visually contribute to, or detract from, the city. What I am more drawn to is the way they are emblematic of the profound wealth divides in London, and the wider world. They hint at a global order where multinational companies, developers and speculators are able to ignore loyalty or responsibility in any particular jurisdiction, instead moving fluidly across national boundaries to make and locate money wherever is most convenient for them. It came as little surprise in my research to find out how many of these developments are owned in tax havens, and how many of the developers claimed to have made financial losses on schemes which were clearly enormously profitable.

More disturbingly, it is a system that many local and national politicians are complicit with. Some of the largest developers are also among the biggest political donors, and on a local level there is often an unhealthy relationship between developers and those who are elected to scrutinise them. In reality the bulk of oversight often falls to community groups and activists. A significant portion of the Metropole book (now available from publisher Overlapse) is research into these things, looking at the financial and political strategies developers employ to push their schemes through and make maximum profit on them.

"Despite the best efforts of architects, developers and planners to ruin the place, the City of London can still be magical"

What do you think of the popularisation of photography? Has the explosion of mobile phone cameras and Instagram been good or bad for photography and photographers?

It has only been a good thing. While I am doubtful how truly democratic photography is, it is something which a vast number of people now use on a daily basis without even thinking of themselves as ‘photographers’. These people are in turn a huge potential audience for those of us working with photography. I find present angst about photography’s mass appeal interesting because it echoes similar concerns that were aired when photography was first invented. Critics like Charles Baudelaire belittled photography as rather vulgar, and Paul Delaroche declaring that painting was dead (although he still continued to paint for a decade afterwards).

A huge number of jobbing painters were put out of work by the spread of photography, but it also meant the best painters were increasingly liberated from the expectations of pictorial realism. They were able to innovate forms of representation that photography could not replicate so well. Oddly the style of Metropole sometimes gets compared to these type of movements, like Cubism and Vorticism. Anyway I think there’s something similar taking place in the widening use of photography by the public, it forces those of us working with photography to innovate different ways of using it, in order to create something which stands out from the great mass of photography out there already.

Where should I be at midnight in London?

Despite of the best efforts of architects, developers and planners to ruin the place, the City of London can still have a magic about it late at night. Wander down some of the alleyways and corridors with half an eye open and at times it can feel as if you’ve travelled back two centuries or more. That is, at least, until you stumble into the next construction site…