Our Roman Dead exhibition at the Museum of London Docklands showcased some of the very latest discoveries of Roman burials in London. But Londoners have been digging up Roman relics for centuries. Meriel Jeater, one of the co-curators of Roman Dead, explores archaeology past and present.

Roman Dead closed on 29 October 2018.

The most recent Roman sarcophagus to be discovered in London

The star object at the climax of the Roman Dead exhibition is a Roman sarcophagus, a huge stone coffin excavated just last year by Pre-Construct Archaeology at a site in Southwark. It's proof that there is more of the legacy of Roman London beneath our city, just waiting to be unearthed.

However, the remains of our Roman ancestors have been found in London from at least the 16th century onwards, if not before. Let's explore these early findings and what researchers into London’s history thought about them centuries ago.

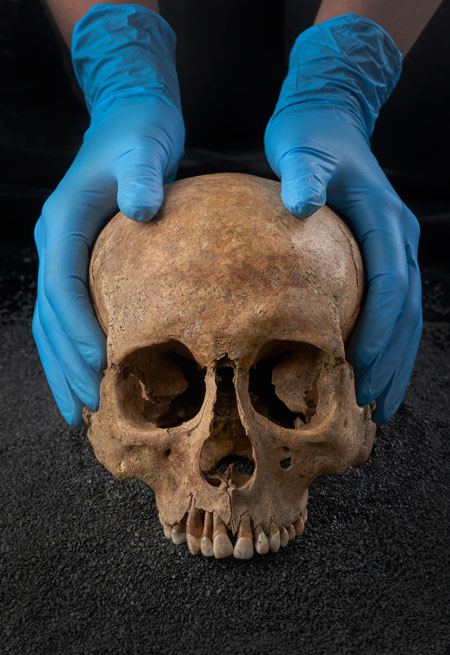

Skull on display in Roman Dead

The medieval ‘historian’, Geoffrey of Monmouth, finished his largely fictional History of the Kings of England around 1136. In it he mentioned Roman beheadings taking place next to London’s Walbrook stream. Did he make this up, like most of the ‘facts’ in his History? Was he inspired by some early discoveries of skulls in the Walbrook? Human skulls have certainly been found in and near this ancient stream for many years and there is much debate about how they got there.

For a full discussion on Geoffrey of Monmouth’s account of this Roman event, see John Clark’s article in the Spring 2018 issue of Spring 2018 issue of London Archaeologist magazine: ‘The Walbrook Skulls Revisited’.

Over 400 years later, another historian, John Stow, gave a detailed description of Roman burials found at Spitalfields in his 1598 Survey of London. In around 1576, the field was being dug up to collect clay for making bricks. Stow wrote ‘…many earthern pots, called urnae, were found full of ashes, and burnt bones of men, to wit, the Romans that inhabited here; for it was the custom of the Romans to burn their dead, to put their ashes in an urn and bury the same…’

Diggers also found glass vessels which, amazingly, still had the remains of liquid inside them. Stow described them thus:

‘there were found diverse vials and other fashioned glasses, some most cunningly wrought, such as I have not seen the like, and some of crystal, all which had water in them, nothing differing in clearness, taste, or savour from common spring water, whatsoever it was at the first: some of these glasses had oil in them very thick, and earthy in savour, some were supposed to have balm in them, but had lost the virtue…’

Glass urn and grave goods from a cremation burial, found in 1873 at Bishopsgate

On display in Roman Dead

These discoveries are reminiscent of another, found in 1873 at Bishopsgate. That summer, the earth in the bottom of a deep excavation cracked in the ‘great heats’, revealing a cremation burial in a glass jar. It had been buried alongside grave goods, including a square glass bottle which contained ‘nearly half a pint of a once aromatic solution’. It’s staggering to think that the contents survived in some form for over 1,600 years. We still have the cremation burial in the museum’s collection. The bottle is now empty, but the cremated remains have recently been analysed by Dr Rebecca Redfern, curator in the museum’s Centre for Human Bioarchaeology. Enough of the deceased’s bones remained to be able to tell that they were an adult when they died. Two pig teeth were also found with the human remains – perhaps this pig had been burnt on the pyre as an offering.

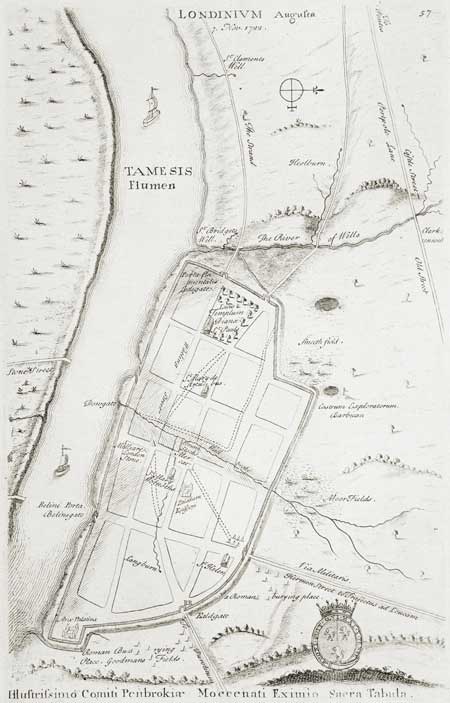

Londinium, 1722

Plan of Roman London, by William Stukeley. ID no. 48.11/693.

Further discoveries were made in the 17th and early 18th century, such as urns with ‘ashes of bones of the dead in them’ in 1678 at Goodman’s Fields outside Aldgate (from John Strype’s 1720 A Survey of the Cities of London and Westminster) and more urns containing ‘ashes, and cinders of burned bones’ at Camomile Street near Bishopsgate (from Remarks Upon the Antient and Present State of London by John Woodward, 1723).

By 1722 enough was known about London’s Roman burial grounds for William Stukeley to include two ‘burying places’ on his plan of Roman London.

Since the middle of the 20th century, several decades of professional archaeological excavation has vastly improved our knowledge of the London’s Roman cemeteries. However, it’s fascinating to know that Londoners in the Tudor and Stuart eras were making important discoveries and learning about their ancestors. Much of what they found has since been lost.

Stow, writing about the Spitalfields burials, said in 1598 that ‘many of those pots and glasses were broken in cutting of the clay, so that few were taken up whole’. Today we know about the burials of around 2000 people from Roman London – who knows how many more have been destroyed over the centuries?

Roman Dead closed on 29 October 2018.

Love Roman Dead? Want to get updates about the city's past straight to your inbox? Sign up for our free Archaeology newsletter.