Photographer Etienne Clément is a celebrated master of shooting the city, winning European Architectural Photographer of the Year 1997. He spoke to us ahead of his October masterclasses in architectural photography, part of our 2018 London Nights season.

The London Nights exhibition closed on 11 November 2018.

How did you become a photographer?

I am completely self-taught. I studied the history of art, badly, in France and I never finished my degree. I’m absolutely no academic – I’ve always done things myself. I did some evening classes to learn how to print my pictures but the rest was trial and error.

I started to photograph in the early 1990s when I came to London, and it took me two or three years to move beyond Sunday afternoon work. Looking back, the very first impression London had on me was of a very austere city, a brutalist nightscape shrouded with rain and fog. That really strongly influenced me – my very first published series of photographs was called Night Vision, focusing on London’s landmarks at night. I would go on long night walks with a camera – this would have been about 1995 – and shoot what I saw.

These were buildings that were often overlooked because of the density of the city, the Barbican, the Post Office Tower, the Trellick Tower. I think they were underappreciated. That series was exhibited at the Architectural Association, and then I began teaching architectural photography.

Would you say you have a unique style of photography?

Normally architectural photography is very straightforward: buildings against a clear blue sky, very clean. My photographs are much more about my interpretation of the buildings than a depiction of them.

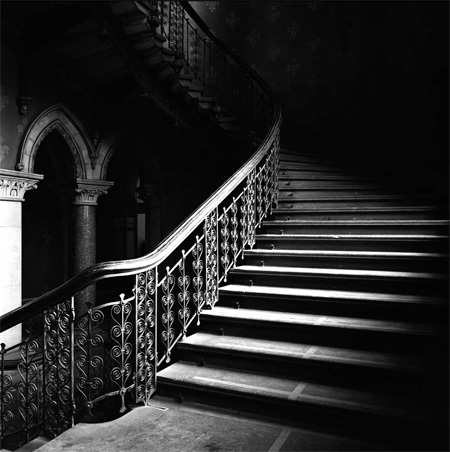

For a long time, I shot mainly in black and white – the way I presented my work was never conventional, very early I was interested in alternatives in terms of printing and presenting. I was printing my work on fine art paper which I would then coat with a photographic emulsion – that helped to distinguish me from other photographers, that I had my own technique which took forever to master. The result was very strong matt black images, which really made these monumental brutal buildings stand out.

Between 1998 and 2002 Etienne had a residency at the Baltic gallery in Gateshead, Newcastle, as it was converted from a derelict flour mill to a major art gallery. His four-year series, Baltic, captures the transformation, including site-specific installation by Anish Kapoor.

Midland Hotel, Etienne Clement

What does London Nights mean to you? What do you think of when you think of the city after dark?

At night the city reveals itself. There is nobody around. There is nothing to distract you from being an observer. The other thing is that you can disappear. You are not noticed at night. If you put up a tripod during the day, people will come and ask you questions. It is nice to be left alone, to work.

Many of the projects I’ve done since Baltic were of places that have been abandoned. Series like Smashed Sinks and Midland Hotel. It’s very attractive to me to be somewhere where you are not supposed to be. That goes back to childhood, the idea of trespassing in the local abandoned house, where you find whatever is left on the floor.

It’s not your world- there is something very edgy about it. In order to get into these places you have to look the part: if you have a hard hat on and people don’t ask questions. The city at night is a little like trespassing – you are slightly vulnerable. If you are in a dark alley and there’s no one around you have to work quickly.

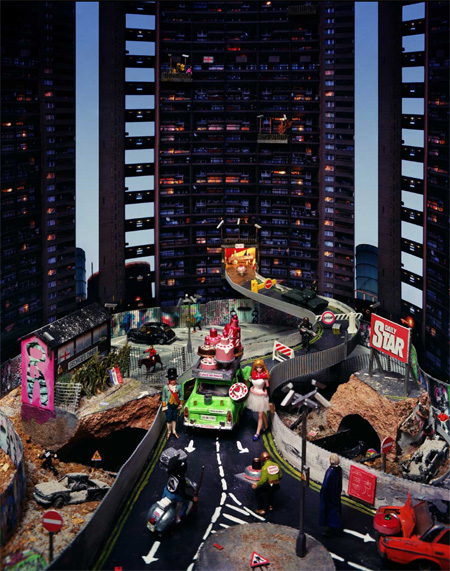

La Nuit de Varennes, Etienne Clément

From the series Eat cake! Says Queen

Etienne’s work today focuses on photographing extraordinarily detailed dioramas, populated with tiny figurines. This seems like quite a change from your building photography – what made you change?

I see this as an extension of my work with architecture – people ask me what I do and I say, I build sets. Sometimes I start from a painting – a 2-dimensional document that I can translate into a 3D set. It was inspired by work photographing those empty tower blocks – I would think, there are so many stories in these buildings, thirty years of human experience that are now absent. People would have moved out in a hurry, leaving behind letters of toys. These were rich reminders that would let you imagine stories about their lives. So I wanted to create these little scenes of human life.

Where should I be in London at midnight?

I would choose the Barbican – on a windy day like today, with clouds, at night.