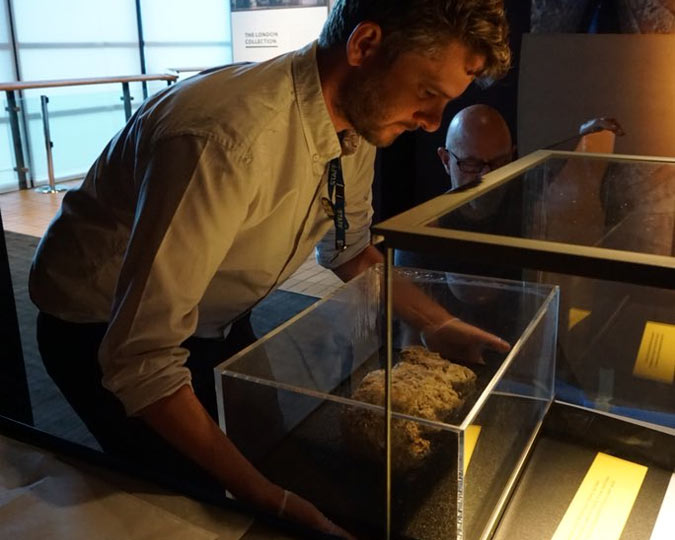

Will Eckersley's Dark City series is entrancing and disquieting. Our London Nights exhibition features several of his shots of deserted streets and dark urban spaces. We asked Will about photography, London, and nocturnal pleasures from trespassing to Netflix.

Photographer Will Eckersley

How did you become a photographer?

The first thing that really started me off was a friend who did a masters degree in graphic design in 2005. I’d been messing about with cameras for about 10 years, and he drafted me in to shoot abandoned buildings on a large format camera for a project he was working on. I really enjoyed the urban exploration (which fitted with my interest in the built environment), and we ended up publishing the results as a book, Left London.

I’ve since done a master’s degree myself in photography having never studied initially. As such, that early project and my subsequent work on London at night, Dark City, had no real knowledge of art photography, or the theory behind it. I was shooting more as a craftsman and simply enjoying the urban landscapes as my subject.

Shops This Way, SE2

By Will Eckersley.

How would you describe your specific work on display in London Nights, your fantastic streetscapes?

I didn’t have many preconceived ideas when I began, but after a few years of shooting I began to formulate a theme: when the built environment is thronging with people, our understanding of it is framed by its inherent functionality. Spaces devoid of people lose that quality, and as such reveal more of their form or underlying design. Heightened by the dramatic lighting from different sources and colour temperatures at night, I began to appreciate this ambiguity I sensed in my relationship to otherwise familiar locations around London.

I had an A-Z map of London and as the project progressed, I went through it grid square by grid square, looking for increasingly ambiguous and liminal spaces. I suppose I was seeking to push the question of how urban design is guided (or not) in such locations. The journey ultimately took me from the centre out to the industrial zones around the north circular, Lea Valley, Thameside and Beddington.

"Reclaim the night for relaxation and revelry"

Wall and brambles, IG11

Will Eckersley.

What does London Nights mean to you? What do you think of when you think of the city after dark?

The old expression to “make hay while the sun shines” posits that we should work hard whenever conditions are good enough to allow it. However, this becomes problematic in a world that’s increasingly unbounded by the cycle of day and night – that is ‘on’ 24/7. Should we be working all the time? In the past, night-time had a vital role in relaxation, revelry, and spiritual practices. I think it’s important to reclaim the night for those, especially in the city.

In fact, I'll be talking about this at the museum's Illuminating the Night evening on 28 September 2018. I hope to explore this through Heidegger’s contrast between meditative and calculative thinking. In a huge simplification of his philosophy (which is mostly beyond my understanding), he sought to critique the hugely influential dualism of Descartes in which we see ourselves as subjects, and the world and other people as objects.

This view is in fact fundamental to Western thought and has persisted from the ancient Greeks to the present. Because it is so orthodox – totally embedded in all of our culture, science, and politics – we aren’t even aware of it as anything other than common sense.

Heidegger identified this, and argued that world and others, thus objectified, become like mere ‘resources’ that we constantly and unwittingly manipulate in this ‘calculative’ mode of thinking. He doesn’t mean that we all act entirely cynically, more that this mode of ‘calculative’ thinking leads to us viewing every thing, person and situation as a possible means to something else, rather than an end in itself.

For example, what does it mean to just ‘be’ in the presence of a tree without an awareness of it as possible timber for firewood, a shelter, a canoe? Simply ‘being’ like that (what he called dasein, ‘being here’) opens the possibility for meditative thought.

In other words, night as a time to just ‘be’, to wander, to enjoy food and drink, to create, to pray, to dance, to be bored, to do things without purpose.

What do you think of the popularisation of photography? Has the explosion of mobile phone cameras and Instagram been good or bad for photography and photographers?

I really don’t know. Because of the huge increase in the number of images now produced and consumed, I do agree with a lot of academics who see photography as more ‘relevant’ than ever before. When popular, consumer photography exploded in the past, it created whole new genres of vernacular image-making, as well as new relationships to cameras and the technologies of looking and being seen. I’d guess we’ll probably say the same about this era in decades to come. It seems that the key driver of this increase is not simply the ease or lower cost of producing images today (digital over film), but more importantly that these images are shared through social networks as a form of communication. They become more like symbols in new form of human language. Optimistically, as this develops, our growing image-literacy may produce the same wonders as our verbal language, like poetry.

However, if technology is a means through which we evolve socially and culturally, it has never been a smooth ride. The relative geopolitical peace of the last 30 years (despite considerable current strain), arguably resulted from the mutually assured destruction of atomic technology and the Cold War. If one day we’re able to communicate poetically and compassionately to each other through images, it will be after a long struggle through the narcissism, bullying and corporate coercion of our current social media ecosystems.

Where should I be at midnight in London?

20 years ago – dancing in a warehouse in Colindale. 10 years ago – probably in the same warehouse with a camera trying to do something clever. Now? Tucked up in bed, or still watching Netflix if I’m having a big night! Where should you be (assuming you want to have more fun than me)? Follow your nose down any darkened alley or fire exit and see where you end up. You’re usually safe if heading away from noise, and before long you might find a strange peace and ambiguity in a hidden corner...