Part art gallery, part fashion show and part brothel, London's pleasure gardens defined the city's nightlife in the 18th and 19th centuries. Curator Danielle Thom takes us into the history of pleasure, from concerts and balloon-flights to drunkenness and debauchery.

Part of our series about London's Pleasure Gardens, the pinnacle of nightlife in 18th and 19th century London. Read more about the Pleasure Gardens: costume; music; masquerades; eating and drinking; toilets.

First published during #RedressingPleasure – thank you for helping us to crowdfund our new gallery of 18th century fashion!

The eighteenth century was the age of ‘commercialised leisure’, according to the historian Sir John Plumb. Thanks to the growth of an urban middle class, rising incomes, and new ideas about how people should socialise and converse with one another, it was a period in which paid-for entertainment proliferated, especially in large, cosmopolitan cities like London.

One of the most significant innovations in eighteenth-century leisure was the pleasure garden; a dedicated outdoor space for entertainment, for which a ticket was needed to gain entry. In London, the gardens at Vauxhall, near Lambeth, and at Ranelagh, in Chelsea, were the largest and most spectacular of their type; while other, smaller gardens were established at Sadler’s Wells, Marylebone and Hampstead – all of these sites were on the rural outskirts of London.

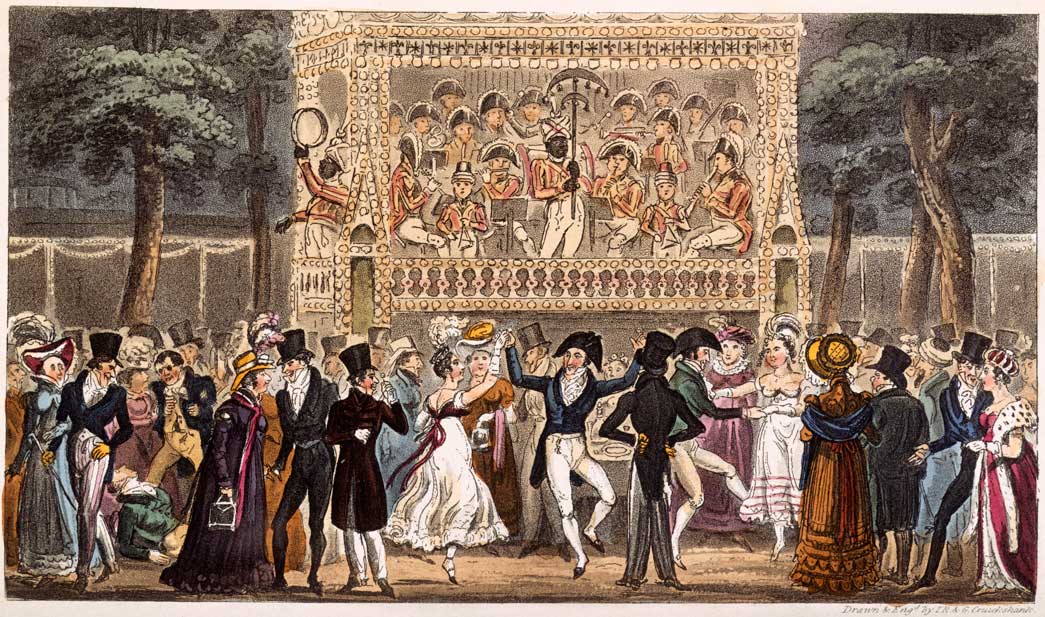

Vauxhall Garden, 1809

Coloured aquatint, Thomas Rowlandson.

They were sites for music, dancing, eating and drinking – and regular fireworks, operas, masquerades and illuminations. Laid out as formal gardens, with shrubberies and miniature waterways, and dedicated buildings for performances and for eating, they were places to see the latest in art and architecture. Ranelagh boasted a pavilion in the fashionable Chinese style, while Vauxhall displayed paintings by William Hogarth and Francis Hayman in its supper booths, effectively becoming the first public art gallery in Britain.

Vauxhall was also the place to go to hear the work of George Frideric Handel, who became a kind of composer-in-residence during the 1730s and 1740s. Aimed at the wealthy, the aristocratic, and the more prosperous sort of merchant and professional families, London’s pleasure gardens were the very best places to see and be seen by the world, arrayed in your most fashionable finery.

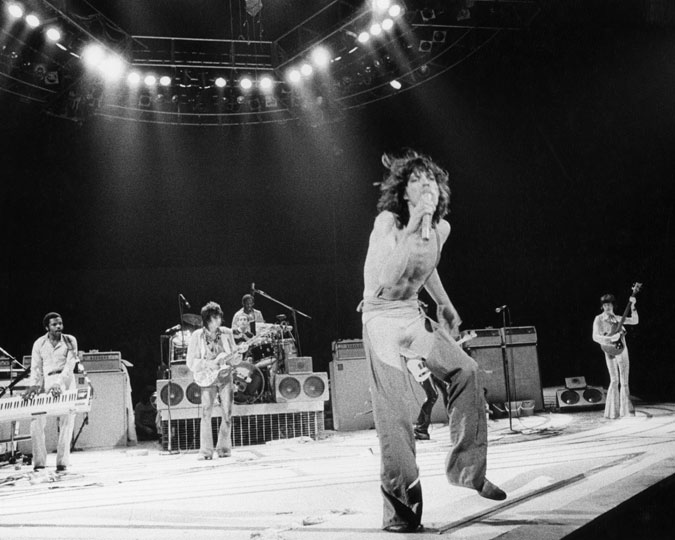

Fashionables at the Vittoria fete, Vauxhall

Engraving, 1814

The first and most important of these gardens, Vauxhall, was established in 1729 by the entrepreneur Jonathan Tyers. While the site had been a place for Londoners to gather and buy refreshments since the 1660s, Tyers realised that there was a market for paid entertainment. He also knew that charging an admission fee (of one shilling) would discourage pickpockets and prostitutes.

The admission fee theoretically guaranteed that patrons would not have to rub shoulders with the lower classes of the city, for a shilling was a substantial sum of money to an apprentice or servant earning just a few pounds a year. Ranelagh was even more expensive – and exclusive – at two shillings and sixpence; and was considered the most respectable option of all.

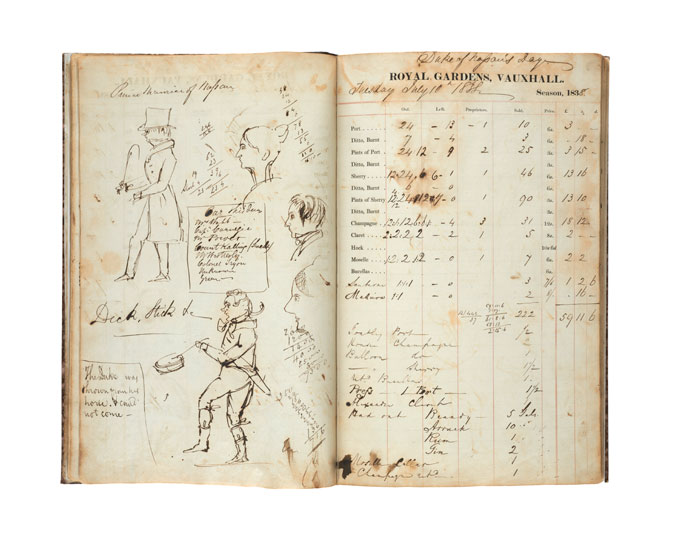

Printed in Macaronies, Characters, Caricatures &c by Mathhew Darly. British Museum collection.

Despite these efforts to keep ‘the riff-raff’ of the city outside its elegant gates, Vauxhall had a slightly louche, dubious reputation. Its wooded groves and shady alleyways were the perfect place for a discreet assignation, and the well-dressed prostitute was associated with the garden to the extent that London printshops sold images with titles like The Vauxhall Demi-Rep’, showing beguiling ladies in expensive but revealing clothing.

One of the most scandalous events at Vauxhall occurred at a fancy dress masquerade in 1749, when the courtier Elizabeth Chudleigh arrived 'dressed' as the classical figure Iphigenia – her costume consisting of nothing more than a thin scarf draped over her body, showing off more than it hid. Again, the press and printsellers had a field day. Even respectable Ranelagh had its disturbances, such as the 1764 riot caused by servants and coachmen angry at the abolition of ‘vails’, or tips.

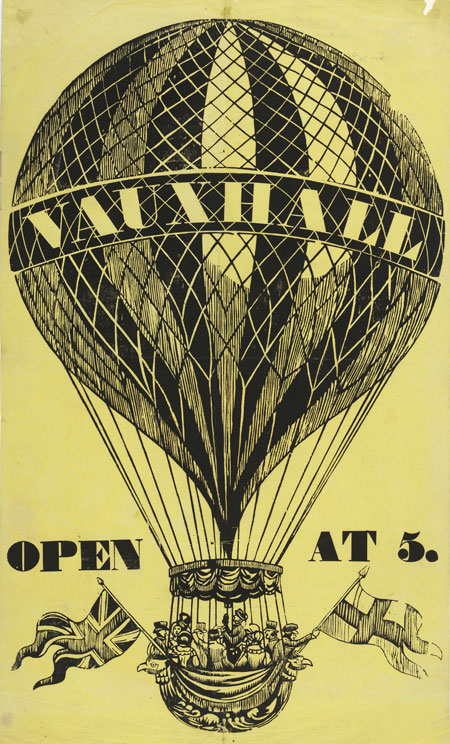

Vauxhall Pleasure Gardens ballooning poster, 1830-1836

Regular balloon flights took off Vauxhall. ID no. A9172.

So vivid was the idea of the London pleasure garden as a place of danger, debauchery and drunkenness that it was frequently used as a backdrop for contemporary novels, ballads and prints. The heroes and heroines of numerous 18th and early 19th century novels end up in a pleasure garden at some point, and usually worse off at the end of the evening than at the beginning of it – from Frances Burney’s virtuous Evelina, pursued through the trees of Vauxhall by men intent on harassment and maybe worse, to William Thackeray’s comic character Jos Sedley, in Vanity Fair, suffering literature’s worst hangover after a night of Vauxhall punch.

There was nothing quite like the London pleasure garden, and no modern equivalent exists. It was a place where the glittering world of wealth, fashion and high culture showed off its seedy underside; where princes partied with prostitutes, and the middle classes went to be shocked and titillated by the excess on display. Simultaneously an art gallery, a restaurant, a brothel, a concert hall and a park, the pleasure garden was the place where Londoners confronted their very best, and very worst, selves. When Vauxhall finally closed in 1859, it was the end of an era, never to be repeated.