On June 9th 2020 the statue of Robert Milligan that stood in front of the Museum of London Docklands was removed by local authorities. Guest writer Kristy Warren explains the background of this removal, and explores the legacies of slavery in statues in London and around the world.

In the wake of Edward Colston’s statue hitting the harbour in Bristol during a Black Lives Matter protest, debates have been reignited around the continued presence of statues and other memorials of those who profited from slavery and colonialism. There are statues, plaques, buildings and streets that bear the names of and uncritically celebrate these men (they are almost always men) across the British Isles. These forms of commemoration sit in public spaces traversed by many people, including the descendants of those who were enslaved and colonised.

What is happening around public memorialisation in the UK is part of a wider movement, as can be seen in this map of monument removals created by Dr Hilary Greene. This map mainly shows monuments removed since 2015, but also provides information on some that were removed earlier. The removed monuments featured in the map are primarily in the United States, with the statues of confederates who were apologists for slavery featuring prominently. However, Belgium, Canada, and the UK are also included. The statues in Belgium that have been removed are of King Leopold II, who was responsible for the deaths of millions of people in what is now the Democratic Republic of Congo.

So far, no statues have been taken down in either formerly colonised countries or the remaining British Overseas Territories in the Caribbean. The landscape is a bit different in the Caribbean as since the late-20th century, when most of the countries gained independence, many new statues and memorials have been erected. These include depictions of those who have been remembered for resisting slavery such as Cuffy in Guyana, Bussa in Barbados and Sally Bassett in Bermuda.

More figurative pieces, such as ‘Redemption Song’ in Emancipation Square in Jamaica, have also been made. Yet, statues and memorials erected during colonisation remain in place and in recent weeks there have been renewed calls to remove them. This includes statues of Christopher Columbus in Trinidad and Lord Nelson in Barbados. That this is a global movement can be seen even in the UK through the renewed calls to remove the statue of Cecil Rhodes in Oxford. This campaign responded to action by students at the University of Cape Town in South Africa in 2015, who successfully demanded the removal of the Rhodes statue on their campus.

In London, there are many contentious statues. Following the removal of the Colston statue in Bristol, the Mayor of London has ordered a review of all statues and street names in London, in part to assess links to slavery. This was accompanied by action from specific councils – either in direct response to recent events and actions, or as a continuation of work already in progress. For instance, Haringey Council is seeking responses from residents about which street and building names need to be reviewed. In Hackney, long-planned sculptures recognising the contribution of the Windrush generation will be unveiled in 2021.

Two days after the Colston statue was removed, the statue of Robert Milligan was taken off of its plinth in West India Docks by landowners Canal & River Trust. This was in partnership with Tower Hamlets Council and the Museum of London, and followed a campaign by local Labour councillor Ehtasham Haque and a statement advocating for its removal from the Museum of London.

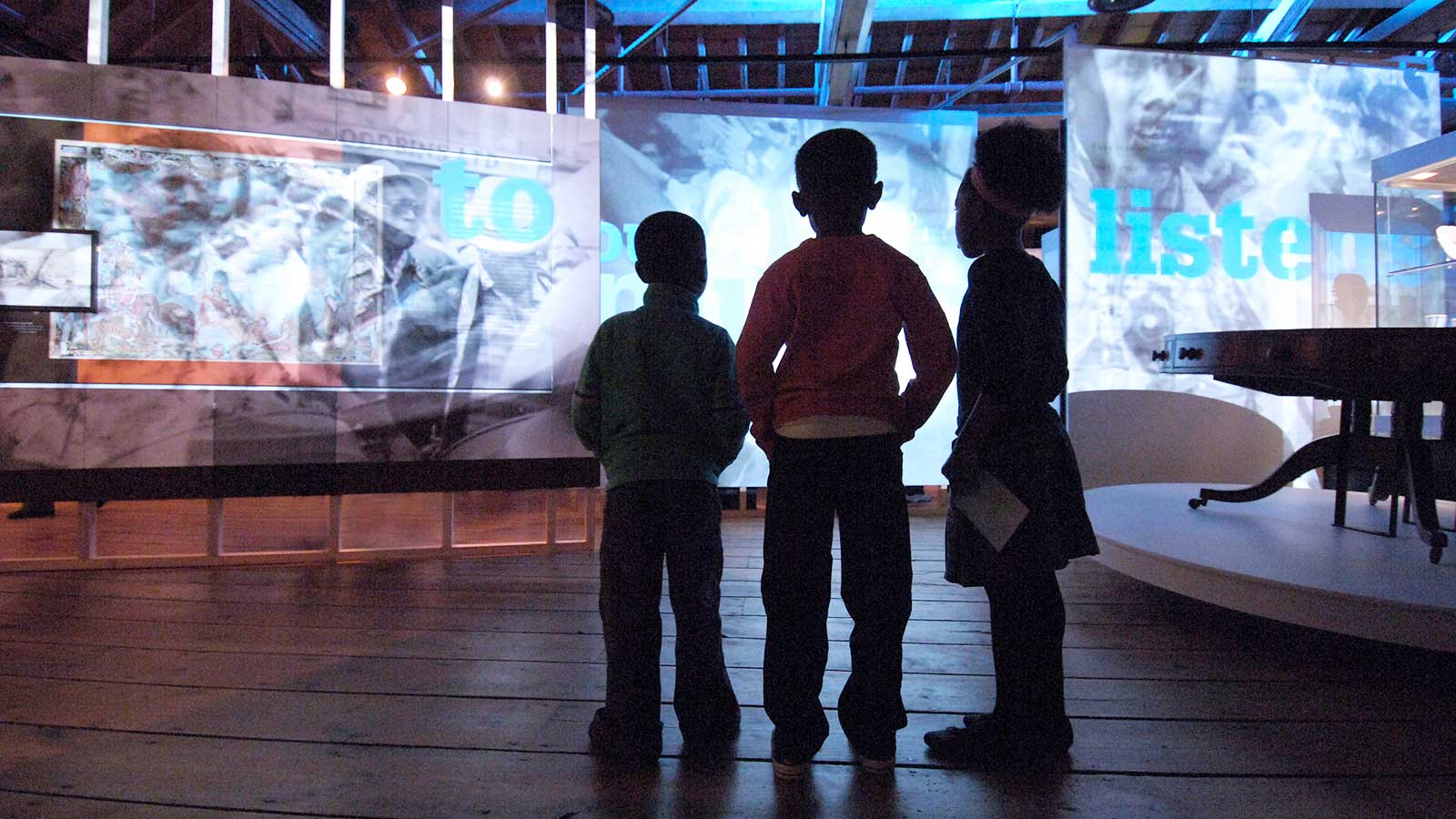

As with Colston, requests to remove the Milligan statue are old. Activists, artists, communities, historians and a range of others have asked that something be done about it for a number of decades. The statue stood outside the entrance of the Museum of London Docklands and was, therefore, something that those visiting the museum had to pass. It provided a constant reminder of the kinds of history that are hidden in plain sight.

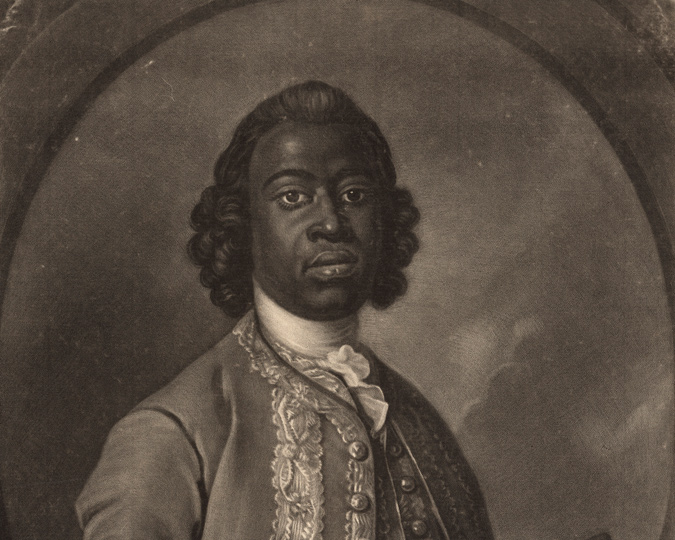

The inscription on the statue’s plinth, while valorising Milligan’s participation in commerce, said nothing about the enslaved people he claimed ownership of, nor those he bought in bulk from slave ships to sell to other enslavers. Before his death in 1809, Milligan claimed ownership of 526 enslaved people who were forced to work on his two plantations in Jamaica. When the London Sugar & Slavery Gallery was opened at the Museum of London Docklands in 2007 a black cloth was draped over the Milligan statue, but no permanent solution was resolved upon at that time.

In 2018, Dr Katie Donington created the film which accompanies this piece as part of the Slavery, Culture and Collecting exhibition which she curated with Dr Danielle Thom at the Museum of London Docklands. The exhibition, explored how George Hibbert invested in several cultural institutions using the wealth he had acquired through slavery and the ‘slave economy.’ The film, which was made with support from the University of Nottingham, interrogates monuments and other memorialisations of Hibbert and Milligan found outside of the museum.

Understanding the link between British wealth and slavery is a significant part of what the debates around memorialisation have been about. This film contributes to these debates. It offers a reminder that there is a difference between rewriting history and bringing hidden injustices to light. For not only do the existing memorials hide the country’s links to slavery; the missing memorials to the enslaved furthers the discrepancy between those whose stories are heard and those who are silenced.

If monuments are so important to remembering the past, why do we not have a prominent monument to the enslaved? Why did the government reject a chance to help fund the charity Memorial 2007’s sculpture, that the present Prime Minister had previously supported?

The question of statues relates to wider debates about how Britain remembers slavery and colonialism. And the government’s unwillingness to engage meaningfully in this debate is not new. In 1999, MP Bernie Grant raised the connection between monuments to enslavers and the continued denial of the contribution of enslaved people during Prime Minister’s Question Time when he said:

"There has been no acknowledgement of the contribution made to the wealth of Britain, Europe and America by millions of African people. The Guildhall and other places in London have monuments to the slavers, not the enslaved."

In his reply, then Prime Minister Tony Blair acknowledged the contributions made by African Caribbean people to the United Kingdom, but did not comment on the monuments

This brings us to a talk given Turner Prize winning artist Professor Lubaina Himid in 2011 called ‘What Are Monuments For?’

In her talk, Himid spoke about alternative guide books she had created, which placed statues to luminaries from the African diaspora within the landscapes of Paris and London. She mused:

"I often wonder how powerful and dignified London and Paris would be now if their citizens and politicians had really sanctioned and paid for […] dynamically visible, beautifully located, commemorations, memorials and monuments to the people of the Black Diaspora."

She ended the talk with a slight adjustment to her question asking: ‘Who are monuments for?’

It is important for us to collectively address who we feel should be commemorated in the public spaces we all share. This includes considerations of alternative forms of memorialisation, as not everything needs to be set in stone. Making room for all the stories that have been forgotten and purposely side-lined also means adjusting the narratives found in museums and radically transforming the school curriculum. It requires a national reckoning of the way Britain profited from the enslavement and deaths of millions of Africans over more than two centuries. It also necessitates addressing the continued denial of the contributions they and their descendants have made to this country.

Note from the Museum of London: Following the removal of the Robert Milligan statue outside the Museum of London Docklands, we are working with the local authority, Tower Hamlets, and the landowners, Canal & River Trust, to discuss the future of this statue. The local community will be consulted about further developments.